Is There Cash on the Sidelines?

Cash on the sidelines is a term that traders refer to in order to describe how much capital is supposedly out there to go into financial assets.

The price of a financial asset is just money and credit divided by the quantity of it. So while things like valuations and determining notional fundamental values of assets is important, it’s really about liquidity that drives asset markets.

The entity with the biggest lever over liquidity is the central bank, so it’s important to know what these entities are doing.

The US Federal Reserve is the world’s most prominent central bank. The ECB and BOJ take care of the eurozone and Japan, respectively. The PBOC oversees China’s monetary policy.

First, it’s important to know why all this cash is around (e.g., higher bank deposits, higher personal savings rates).

This comes from knowing the different forms of monetary policy, what type or monetary policy paradigm we’re currently in, and what effect that has on the economy and markets.

Categories of monetary policy

There are three main general categorizations of monetary policy.

Monetary policy #1: Interest rates

First, there’s interest rate-driven monetary policy. This is where the central bank adjusts short-term rates up and down to change the incentives governing private sector credit creation.

When that hits about zero, then that’s gone.

That means the boom-bust cycle, as we commonly know it, is gone.

In 2019, central banks around the developed world had virtually given up on trying to normalize interest rates.

They didn’t want to tighten because debts relative to income were so high. That creates asymmetric risks when it comes to any potential decision to tighten policy.

Inflation wasn’t a problem, but it’s easy to topple over markets and then the economy with just a small amount of tightening. The Fed found this out in Q4 2018.

They didn’t tighten because the ability to ease with such low interest rates was limited.

In a typical downturn, central banks ease by about 500bps to get a floor under the credit market. That helps to stabilize the financial economy and then the real economy at some point thereafter. Markets lead the economy.

A cut in interest rates normally produces an expansion in credit.

But if debt to income ratios are high and you can’t cut interest rates to generate that kind of credit expansion, then the ability to effectively save the economy, when necessary, is low.

So, they get into a situation where central banks don’t want to cause a downturn because they won’t be able to pull out of it. As a result, they don’t tighten.

Monetary policy #2: Asset buying

When short-term interest rates are about zero, they move onto quantitative easing, a type of asset purchase program. That works when risk premiums are high and liquidity is tight.

That’s also no longer the case throughout the developed world.

Monetary policy #3: Monetary and fiscal policy coordination

The third type of monetary policy is a type where it’s driven by fiscal policy in determining how much money and credit is needed and the central bank supports those actions.

Some might call this ‘MMT‘ but it’s how it’s always worked historically when money and credit expansions couldn’t be generated in normal ways.

Political risk

While fiscal and monetary coordination is essential, and this is always how it’s worked historically, it’s fraught with political risk.

When you have higher wealth gaps and opportunity gaps in an economy, and especially when you have an economic downturn, this spills into social movements. In turn, this impacts what kind of leaders get chosen. This naturally has a feed-through into ideological gaps and greater political polarization.

For many things to get passed, there needs to be some consensus and middle ground.

There’s always the risk that it’s not adequate and either nothing gets done or not enough gets accomplished.

Both parties are likely to alienate the other if they’re trying to use “stimulus” bills as part of their power plays – e.g., writing in certain agenda items to pass along with everything else.

The thinking is that if certain spending bills are badly needed, then sneaking in pet legislative ambitions would be the most opportunistic time to do so because they are more likely to get passed.

When each side picks up on the discreet tactics of the other, saying that such items have nothing to do with what’s actually important and really needs to get done, then they can claim that their opponents are trying to torpedo everything to detriment of society for something extremely small. Such is the environment associated with the political decision-making process.

It also presents a new type of world that all market participants need to understand. How to allocate capital, what assets to invest in, and what portfolio approaches to take is important to understand.

The economy turns down, and the central bank rectifies the imbalance with a cut in interest rates in terms of the normal way it works.

That didn’t and couldn’t happen because monetary policies one and two were out of gas, so it transferred over into the fiscal side of government with the monetary side assisting in the ways they could.

Debts continued to climb to offset the lost incomes from the distancing process.

Debt creates a liability on one side of the balance sheet (heavily in the public sector) and has created a lot of cash and savings on the asset side of the balance sheet(heavily in the private sector).

But it’s come at the trade-off of severely limited potential growth rates in the post-virus world.

It also increasingly puts the emphasis on fiscal policy, instead of monetary policy, as the main lever over the economy. You may get more fiscal policy support (or not) based on the individual willingness of any country to do so.

Each country runs into its own constraints in that process. Eventually the debt becomes too high and the printing of money to fill in the gaps creates problems in various ways (e.g., currency devaluation, inflation, balance of payments problems).

It’s the biggest issue for emerging markets because they don’t have much global savings in their currencies – namely, they aren’t reserve currencies.

After that, the next countries to run into constraints would be smaller reserve currency countries (e.g., Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Great Britain, Japan, Switzerland). Then followed by developed Europe and the US.

As a result, the biggest recipients of all this liquidity are the euro area and the US, using the power of their reserve currencies. They can simply push this process further than other countries. But there are always constraints to everything.

The US is seeing pressures on its exchange rate as the result of its policies, both relative to other global fiat currencies and relative to non-fiat contra-currency stores of wealth like gold.

And these important divergences are important to point out, as this is mostly a matter of what’s going on in the West. But this tertiary monetary policy regime doesn’t apply to China and most countries in the East.

The economic destruction and liquidity expansion – the latter being the whole cash on the sidelines element – is really a figment of the West and not the East.

What to do about cash?

As a result of all these policies, there’s a lot of cash being held. People and businesses are not sure what comes next. And in any crisis, they begin saving more.

Cash doesn’t yield anything in the developed world, so it’s not much of an asset. It loses spending power over time.

People know this and these are the incentives central banks create to get more investment and spending in the real economy.

So, does cash on the sidelines get liquidated, does it get swapped for another asset eventually, or does it stay in place as a longer-lasting “rainy day” fund?

Even though cash is the worst investment over time, people still need to save. And a lot of people like cash simply because its value doesn’t move around much like taking risk in other assets.

Around the world, the accumulation of cash balances was around 5x what you normally see in response to the virus.

New cash became about 13 percent of GDP globally, or 17 percent of GDP in the US.

That’s a huge amount of cash to be sitting in bank accounts.

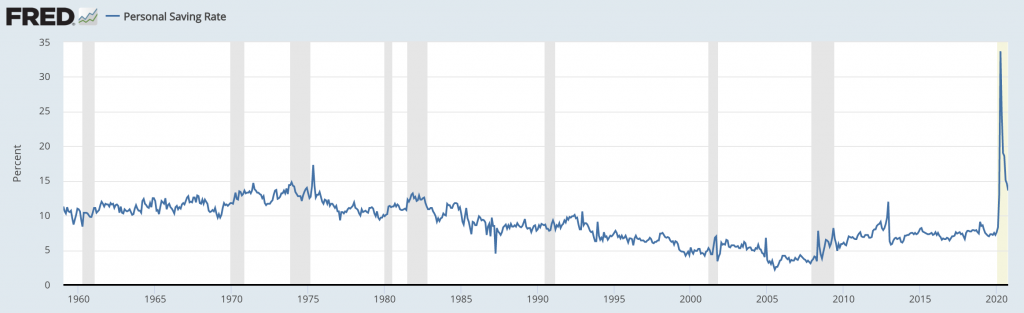

Savings rates are also important.

Personal savings rates are defined as personal savings as a percentage of disposable personal income (DPI). It’s calculated as the ratio of personal savings to DPI.

Personal savings is equal to personal income minus personal outlays and personal taxes. It is commonly viewed as the portion of personal income that is used to provide funds to capital markets for investments in equities, bonds, and so on, or to invest in real assets, such as homes.

Savings rates matter a lot as a potential source of “juice” for asset markets.

In the US in July 2005, because of the bubble that was getting started in housing, savings rates were only 2.2 percent. That’s the low point on the graph bel0w.

From 1960 to 1985, 10 to 15 percent savings rates were common. From 1985 to 2005, 5 to 10 percent was normal before dropping again.

They then returned to the 5 to 10 percent range after the financial crisis.

Personal Savings Rate (US)

Why were they so high in the 1960s and 1970s? There’s likely the element of those individuals growing up in or living through the sparse 1930s period, where many people developed strong savings and financial cautiousness mindsets.

As the new generation came into adulthood, growing up in the post-1945 boom period, those savings rates began to decline more or less until the financial crisis.

Then it rose back up a bit, though central banks orchestrated a historically great bull market in stocks by lowering interest rates to zero and buying financial assets as part of the main two forms of monetary policy (much as they did back in the 1930s).