The 5 Components of Interest Rates

An interest rate is a percentage of the principal amount of money that a debtor (the one who borrowed) owes to a lender/creditor (the one who distributed the sum through a loan or a similar credit disbursement).

There are five principal components of interest rate determination, and each affects the interest rate in its own particular way. Some may not apply to every type of contractual financial debt.

The first three are more central to the idea of a loan, while the latter two are more applicable to a debt security or credit asset, such a bond.

Key Takeaways – The 5 Components of Interest Rates

- Real Risk-Free Rate: This component is the baseline interest rate in a scenario where there is no risk associated with the loan (e.g., government lender who can print its own money).

- Expected Inflation: This component accounts for the anticipated decrease in the purchasing power of money over time due to inflation.

- Default-Risk Premium: This component is an additional rate added to the base rate to compensate for the risk that the borrower may default on the loan.

- Liquidity Premium: This component is added to compensate investors for the risk associated with less liquid assets, which cannot be easily converted to cash.

- Maturity Premium: This component reflects the increase in interest rates for financial securities with longer maturities.

1. Real Risk-Free Rate

The risk-free rate assumes that there is no risk or uncertainty in distributing a loan. Rather, the rate is exclusively based on the advantage for the borrower to spend now and pay later.

This runs in contrast to the interest of the lender to provide a full sum of money only to collect it in steady installments later.

In order for the lender to agree to this transaction, an interest rate must be involved that requires the borrower to pay back more than he initially borrowed.

This will naturally fall at some price where the lender believes it would be a profitable financial decision to make the transaction.

2. Expected Inflation

Inflation is a reality for any healthy economy (just ideally in a smaller amount).

It incentives people to spend their money to keep consumption in an economy high (an essential part of a nation’s GDP), rather than hoarding their cash believing it will be worth more later as it would in a deflationary environment.

Central bankers always want to avoid deflation so they’ll target an inflation rate of at least zero. It helps to output as high as possible.

When your grandma laments how gas prices used to be only 25 cents per gallon when she was a young girl, chances are that gas prices might not be all that far off from what that 25 cents means in today’s money.

Prices are anticipated to rise over time in a market based on the rate of inflation. Therefore, the purchasing power of the currency will be expected to fall over the span of time in which the loan is paid back.

Therefore the lender will include this component into the interest rate in order to compensate for the likelihood of that sum of money having less value in the future. This is often referred to as the nominal interest rate, which is the sum of the real rate and inflation rate.

Lenders naturally want a real return on their money.

3. Default-Risk Premium

Whenever a loan is provided to a borrower, there is always some chance that the payments won’t be paid on time or it won’t be repaid in full. Lenders compensate for this risk by adding the default-risk premium to an interest rate.

This is where the concept of credit scores come into play.

They help to determine the creditworthiness of the individual to evaluate the risk of lending to that particular individual. Borrowers with low creditworthiness (as determined by some form of scoring metric) will have high default-risk premiums integrated into the final interest rate.

Borrowers with high creditworthiness, by contrast, will have low default-risk premiums.

4. Liquidity Premium

Liquidity is a measure of how easily something can be converted to cash. Something like short-term US Treasury bonds can be easily converted into cash.

Since there is minimal risk inherent in this type of financial security, the corresponding interest rate attached to it (how much the investor will profit) is low as a result.

Assets that are readily convertible into cash (i.e., liquid assets) are considered more valuable. The overcome this discrepancy in the securities market, higher interest rates are attached to less liquid securities.

Other types of bonds with longer maturity rates and less liquidity (e.g., bonds that were sold by a relatively small municipality to fund the building of a public project) will be expected to have a higher interest rate attached to the principal amount invested to compensate the investor for the higher level of inherent risk involved.

If the interest offered is too low on a high-risk asset, investors will be largely unwilling to purchase the security.

The interest rate, like the other components, is hence naturally a product of supply-and-demand forces.

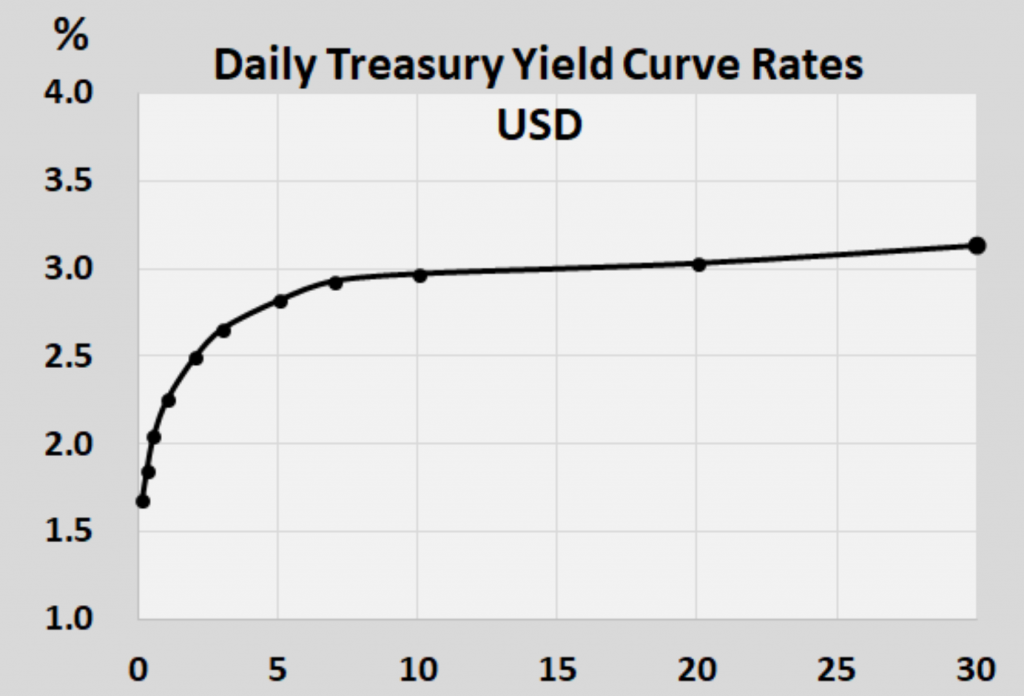

The following graph shows an example of the general side-opening parabolic shape of the yield curve:

5. Maturity Premium

As discussed briefly in the preceding section, maturity premium involves how interest rates will tend to increase the longer it takes a financial security to mature.

This compensates the investor for purchasing a security for which he or she has to wait longer in order to receive full payment. Maturity premium is seen throughout the financial sector.

With respect to mortgage interest rates at any given point in time, a lending agency will offer a 15-year at a lower interest rate than a 30-year.

Graphically, the maturity premium is similar to the liquidity premium. For example, a bond with a 5-year maturity will have a lower interest rate than one with a 30-year maturity.

But the yield won’t be six times as low as it would be if interest rates were roughly a function of the ratio in maturity dates.

A 5-year normally has an interest rate somewhere around half that of a 30-year. The function is non-linear as a result.

(Source: Federal Reserve)