The Complete Guide to Cash Flow Analysis

In this article, we cover the basics of cash flow analysis.

In trading and investing, cash flow is what gives businesses value.

The value of a business is the amount of cash you can take from it over its life discounted back to the present.

So, understanding cash flow gets at the heart of where companies should ultimately trade.

What is cash flow?

Cash flow refers to how an organization or firm discloses its cash receipts (inflows) and cash payments (outflows) during a given quarter, fiscal year, or general reporting period.

Cash flow is the basic means by which businesses will report their liquidity or their ability to service debt.

This necessitates having cash or so-called cash-like securities (assets that can be quickly converted to cash) available to make these payments.

What is the purpose of a cash flow statement?

Evaluating the cash flow of the past period – commonly within the past month, quarter, or fiscal year – gives one the ability to do the following:

- make sensible estimations of cash flows in subsequent periods

- evaluate management decisions

- determine the ability to pay certain expenses (wage, creditor payments, dividends to shareholders), and

- show how the firm’s earnings – i.e., net income – relate to the company’s cash flows

Cash flow shows where cash inflows are derived from within a given period. It also shows the various types of business activities where the cash was put to work.

Analysis of the cash flow statement enables a company’s management team to make more effective cash planning decisions.

Effective cash flow management also ensures that there’s an appropriate balance between cash inflows and outflows.

Cash management

It’s entirely possible that a company with healthy unit economics can run into cash management problems.

For example, let’s say a company’s operations involve content creation to earn ad revenue.

The company’s cash management may entail needing to pay content creators right away but are paid by the ad management companies on a net-60 basis (60 days after ad revenue is earned).

This means needing to keep at least 60 days’ worth of cash in reserve to pay content creators while they wait to receive the money they’re owed.

The cash flow statement shows efficiency

The cash flow statement also shows how efficient a firm tends to be in generating cash from its regular business operations.

There are three main parts to a cash flow statement, comprising:

- cash flow from operating activities

- cash flow from investing activities

- cash flow from financing activities undertaken

What exactly is ‘cash’?

Cash is generated from revenue minus expenses.

Cash comes in the form of:

- what’s immediately available

- cash reserves in a bank account, or

- cash-like equivalents, such as short-term investment assets that are highly liquid and can be readily converted into cash

Let’s look at each part involved in cash flow analysis:

Cash flow from operating activities

Cash flow from operating activities involves any cash flow related to the company’s standard operations:

- Sales of goods and services distributed

- Payments made to goods suppliers and those who provide products or services

- Payments to employees and any other additional expenses (such as transportation costs)

A company’s operating cash flow must remain positive for it to be a self-sustaining business over the long run.

Many businesses that need to spend in excess of their revenue before they attain enough scale to be self-sustaining will need to get the cash from somewhere, either from the founder(s) cash reserves or an outside investor.

To determine operational cash flow, this is the general accounting procedure:

-

-

- + Depreciation and amortization expenses

- – Gains

- + Losses

- + Decreases in current assets

- – Increases in current assets

- + Increases in current liabilities

- – Decreases in current liabilities

- + Net income

-

= Net cash flow from operational activities

The total cash flow from operating activities is of particular interest to investors. Companies can have positive cash flow by raising capital (increases cash flow from financing) or through positive cash flow from investing (e.g., skimping on capital expenditures).

Cash flow from operating activities is a representation of how a business earns its money and its ability to do so.

The direct and indirect methods of calculating cash flow from operating activities will be discussed later in the article.

Cash flow from investing activities

Investing activities reflect changes in an organization’s cash holdings due to investment gains or losses with respect to the financial markets, asset sales, new capital expenditures, or investing activities in any operating affiliates or subsidiaries.

This includes changes in the amounts spent on investments to help the company grow its earnings. This can include capital assets, such as plant, property, and equipment (commonly abbreviated PP&E).

Investing Inflows

- Receipts from the disposal of PP&E and other assets

- Proceeds from the disposal of debt/credit instruments

- Gains from selling stock/equity instruments

Investing Outflows

- Acquisition of PP&E and other assets

- Purchase of debt/credit instruments

- Purchase of stock/equity instruments

- Purchase or sale of long-term assets

- Sale or maturity of investments

Cash flow from financing activities

Cash flow from financing activities includes things that show a company’s ability to build capital and pay or repay credit and equity investors (e.g., paying coupon and principal, offering cash dividends). This can include things like issuing greater quantities of stock, buying back stock, and/or adding loans or changing the terms of credit agreements.

The net cash flow from financing activities provides the public with a general summary of the firm’s financial strength.

For instance, a business that relies on raising new debt or equity in order to raise cash could have problems with its cash flow if the capital market valuations fall broadly, which leads to a period of diminished liquidity and softened demand for financial assets.

Cash flow from financing activities goes by the following formula:

Cash from issuing stock or debt – (Cash paid as dividends + Stock or debt bought)

Calculating Operating Activities: Direct and Indirect Methods

There are two main ways to calculate cash flow from operating activities: the indirect method and the direct method.

Indirect method

The indirect method of calculating cash flow involves looking at the difference between net income and net cash, as provided by operating activities

Direct method

The direct method of calculating cash flow involves looking at the reports of all cash receipts and cash payments, as provided by operating activities

Both the direct and indirect methods get to the same result

Both the indirect and direct methods will produce the same figure when calculated correctly, assuming that the information available is transparent and accurate.

For the indirect method, the calculation is as follows:

-

- + Net Income

- + Depreciation and amortization (D&A)

- + Losses from Sale of Assets (found in the investing activities component)

- – Gains from the Sale of Assets (also found in the investing activities component)

- – Increases in Current Assets

- + Decreases in Current Assets

- + Increases in Current Liabilities

- – Decreases in Current Liabilities

= Net cash flow from operating activities

For the direct method, the calculation is as follows:

-

-

- + Cash received from customers

- – Cash paid for inventory

- – Cash paid for operating expenses

- – Cash paid for income taxes

- – Cash paid for interest

- + Cash received from dividends and interest

-

= Net cash from operating activities

In basic accounting, you learn that there are basically eight steps involved in completing an entire cash flow statement.

1. Always start with Net Income

2. Adjust Net Income for any non-cash gains and expenses (depreciation is a common one)

3. Identify cash inflows and outflows based on changes in current assets and liabilities

4. Sum assets and liabilities to find the net cash flow from operating activities

Note: Assets decrease cash flow as this is money that must be paid out. Liabilities increase cash flow as they represent money that’s taken in. If you acquire an asset, that’s money that’s paid out. If you borrow more (a liability), for example, that represents an inflow and impacts cash flow positively.

5. Changes in long-term assets give net cash flow from investing activities

6. Changes in long-term liabilities and equity accounts give net cash flow from financing activities

7. Take the sum of the cash flows from operations, investing, and financing activities to find the net change in cash position

8. Add the net change in cash to the beginning cash balance to yield an ending cash balance

Note: Total change in cash from the period is equal to cash earned from operations, cash earned from financing, and cash earned from investing. The beginning cash balance is simply the cash balance from the beginning of the period. The ending cash balance is the sum of the beginning cash balance plus the total change in cash.

The cash flow statement feeds into the balance sheet. By virtue of it being a balance sheet, it should balance in the end. Assets should be equal to liabilities plus shareholder’s equity.

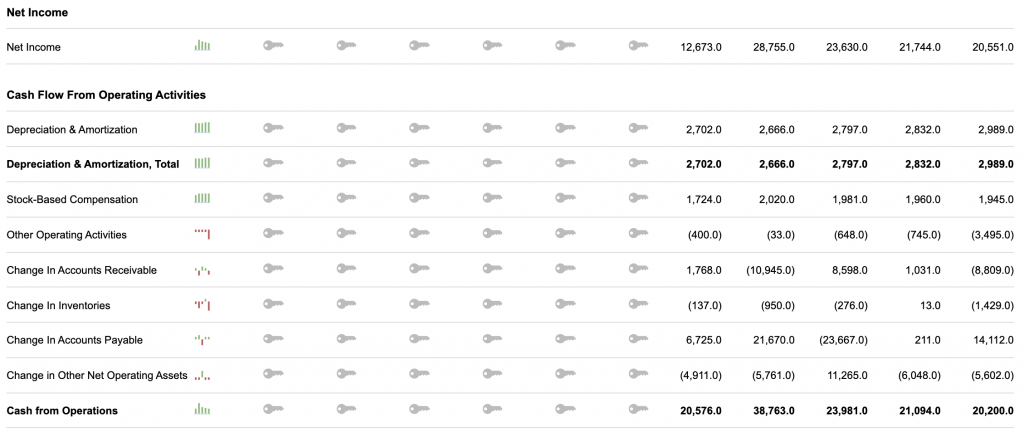

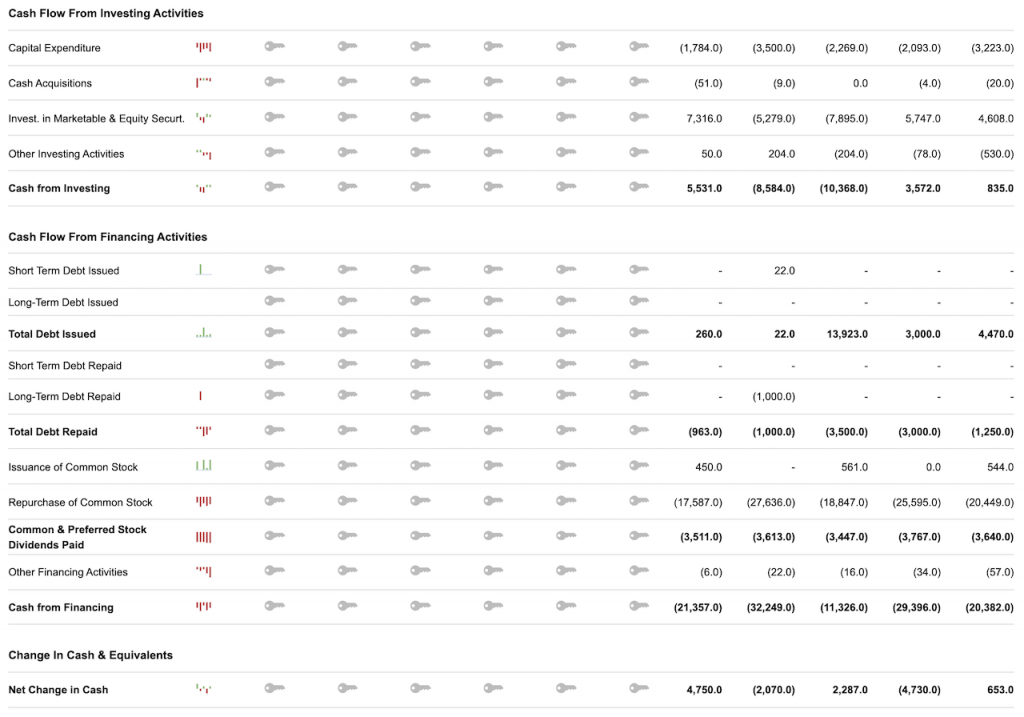

One example of a company’s cash flow statement, in this case, Apple (AAPL):

Net income + cash flow from operating activities

Cash flow from investing activities + Cash flow from financing activities

Importance of Cash Flow

Having strong cash flow is the most fundamental component to any profit-making entity.

For anything to be sustainable, revenue must be equal to expenses, and assets must be equal to liabilities.

A negative cash flow position involves taking on liabilities, which can be dangerous.

This goes for any individual, family, company, organization, and government (though a national government can print money).

Businesses that have problems with cash flow will have a difficult time remaining solvent even if they happen to be net profitable.

Some companies will also engage in accounting tricks to help overstate earnings and/or cash flow.

Looking at each step in a cash flow statement individually will help in determining any areas where a company can improve.

All companies are encouraged to maintain a cash flow budget, as it provides a means of predicting cash flow for potentially many months in advance.

Of course, the longer one tries to predict cash flow into the future, the harder it naturally becomes.

Improving cash flow will make a business more robust and successful. Accelerating cash inflows and delaying cash outflows can be part of doing so, as well as developing a cash flow budget.

Based on the management of a company’s cash flow, a business might find itself with a surplus of cash that it can then do several different things with.

In this case, the company will understand that it may do well to invest the extra money in the case of a surplus in order to earn investment income or borrow money in the case of a cash deficit.

Higher cash flow also gives a company more power, in general.

With more cash on hand it can, for example:

- expand by identifying profitable investments into new technology, capital assets, and new workers

- pay out dividends to shareholders

- have more of a say over public policy to influence results in its favor

What are some drawbacks to a cash flow statement?

A cash flow statement is intrinsically limited, given that future growth potential is not a consideration. It’s backward-looking.

Cash flow statements are based on past business operations.

A company that might be developing a new product may be on the verge of deriving lots of revenue from it.

But looking at the cash flow statement alone, it isn’t possible to determine the future valuation of the company. This is why using a company’s financial statements and using extrapolations to determine valuation going forward isn’t a robust way to do things.

This is why management teams will signal to the market what could be or what might be reasonably expected.

Further, the cash flow statement is not inherently a form of analysis. It’s just a report.

It displays numbers and data on where cash might be flowing. But it doesn’t take into account what the best financial decision(s) might be as it pertains to cash flow.

Where is the best ROI?

For example, would a company best be served by investing more into:

- equipment

- issuing more stock or debt

- hiring more workers

- paying off pre-existing debts

- undertaking a new project

- shuffling resources from one project to another

- selling a business

- acquiring a business

It’s impossible to tell from the cash flow statement on its own.

Cash flow statements also cannot shed insight into the profitability of a firm. This is because any non-cash charges (e.g., depreciation) are ignored when cash flows are calculated from operating activities.

Moreover, accrual is not taken into account.

Accrual is a method by which income items are recorded when they are earned and deducted when expenses are incurred.

Certain negotiations and agreements are not figured into the cash flow statement even though they are a common part of doing business.

Alterations to the cash flow statement do not necessarily indicate something is amiss with the company. It might just be that cash flow has shifted.

Cash flows aren’t static; they can change over time due to several factors, including:

- Changes in cash tied up in accounts receivable (money that is owed to the company) and inventory because of changes in sales levels (e.g., higher sales lead to more cash coming into the company)

- Changes in working capital, like accounts payable (A/P), payroll, taxes owed, and so on, as a result of period demands or current production or inventory procurements (e.g., slower production rates may mean there are cash shortfalls in the periods when cash is tied up in inventory, whereas faster production times may mean cash balances are naturally higher).

- Changes in taxes owed because of how cash is being handled or due to changes in cash outlays for operating costs.

The cash flow statement is the most important of the three financial statements because cash earned is the most important thing about a business.

But it should not be used alone because it doesn’t provide the full picture, rather it shows only a portion of it.

Cash flow statements are merely summaries of cash flows from operations and other sources and uses of cash.

Cash flow statements are also put together by company accountants using certain methods that might have limitations if trying to bring meaning to them or use them as windows into companies’ operations or insights into whether they are healthy entities.

Cash flow statements don’t capture all cash-related effects and cash receipts and cash payments that might impact a company’s cash balance.

Variations in cash flow

Another drawback is that cash flows can vary widely from one year to the next (or even one quarter to another) for a number of reasons.

But it isn’t necessarily meaningful.

For example, suppose an abnormally large amount of cash was used during a period for inventory purchases. In that case, because production levels happened to be high or to get ahead of price increases – the cash flow statement might reflect the company doing worse, even though it’s not really a reflection of that.

Its cash went down, but it simply stocked up. If prices were to go up or it kept a limited amount of inventory out of the hands of competitors, this drop in cash could be viewed as a good thing to help sell more, protect margins, and so on.

Cash balances aren’t profits

An additional cash flow statement drawback is that cash flow statements can produce cash balances. But cash balances aren’t profits.

For example, if a company had inventory (an asset) drop in value by $1 million, the cash position would go up, holding all else equal, but what was reduced was its ability to generate more cash because in most businesses, acquiring inventory ups their earning potential.

Therefore, the cash flow statement doesn’t measure cash flows directly; rather it’s a summary of those cash flows that often change based on what inputs are used to put together the cash flow statement – such as depreciation calculations – and how short-term accounts like accounts receivable and accounts payable levels change during a certain period.

It can be difficult for these statements to provide insight into areas like how much cash is really available or if there may be some issues with managing it (e.g., if accounts receivable or inventory experiences large changes).

The cash flow statement isn’t meant to replace the income statement, which is necessary to help analyze a company’s operating performance and its ability to create value for shareholders (and how it might be able to organically fund payouts like dividends).

The cash flow statement should only be used as a supplement to provide more insight into cash-related changes.

However, by not including cash flow information, analysts and investors might overlook certain trends in operations that could impact their views of profitability or potential dividends.

(A cash flow statement can be built out using the income statement and balance sheet.)

Conclusion

Cash flow is a means of representing the movement of money in or out of a business within a specified time period, such as a month, quarter, or year.

It can provide insight into the value of a company and its general economic health as a whole.

It’s essentially a measure of a business’s liquidity, or simply its ability to pay off its debts.

They report on matters, such as:

- operations (how a company fundamentally makes money)

- capital expenditures (which are costs incurred to further expand a business)

- investing activities (which would be cash spent on acquisitions)

- financing activities (such as distributions made to owners or raising debt capital through issuing bonds, for example).

A company can be insolvent even if it is profitable due to a shortfall of cash impacting its ability to effectively pay off its outstanding payments and meet current expenses.

A firm’s cash flow statement will allow it to determine how it will make ends meet in the short term.

But they naturally cannot display the full scope of a company’s strategies or resources for meeting expenses and liabilities and continuing to make a profit in the long run.

The cash flow statement is supposed to be a snapshot of cash flows from all sources and uses within a specific time period or across multiple periods. The cash flow statement is merely an end result of cash flows between operations, and cash receipts and cash payments from other sources (e.g., interest expense, interest income, loans, stock sales, stock buybacks, and so on).