Tiered Interest Rate System: How Does It Work?

Because negative interest rates will be a part of the euro area economy for a long time, central bankers are increasingly focusing on the harmful side effects that they might bring and getting around the matter with a tiered interest rate system.

Namely, there is the issue of bank disintermediation. In simple terms, disintermediation means lower bank profitability, or the inability for banks to make a profit altogether. This is generally correlated with lower interest rates because they can’t lend as profitably.

When banks can’t lend profitably, credit creation will drop. This is bad for the economy. Credit is essentially the lifeblood of the economy and broader financial system. About 93 percent of all transactions in the US economy are made with credit. Staying with respect to the US only, currency and reserves in circulation are around $5.5 trillion ($1.7 trillion in currency; $3.8 trillion in reserves) and the total amount of debt is around $74.3 trillion. This means the amount of credit in circulation is nearly 14x higher than the amount of currency and reserves.

This has led to the idea of a tiered interest rate system and figuring out the mechanics and technicalities of how to put it together.

Understanding the new interest rate system is also important for traders and investors.

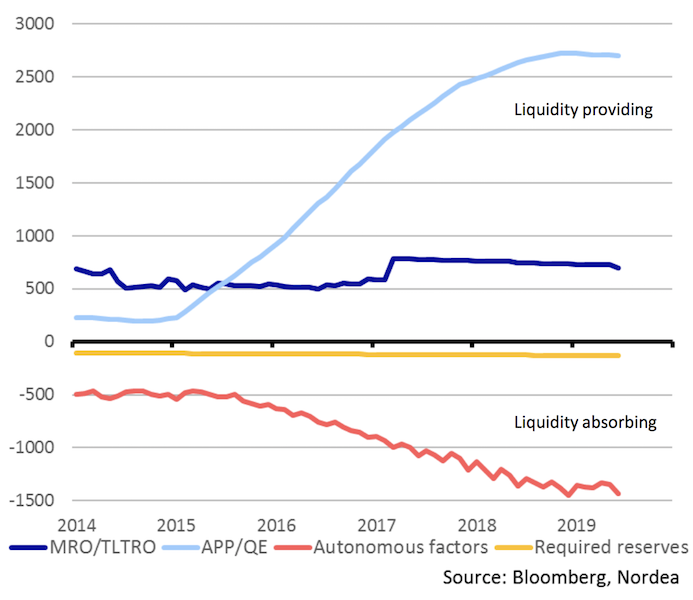

Changes in monetary policy influence the liquidity picture. This impacts how money and credit flow through the system. This process moves financial asset prices. Knowing what’s liquidity providing and what’s liquidity absorbing is important to know. If central banks provide liquidity it’ll go into assets.

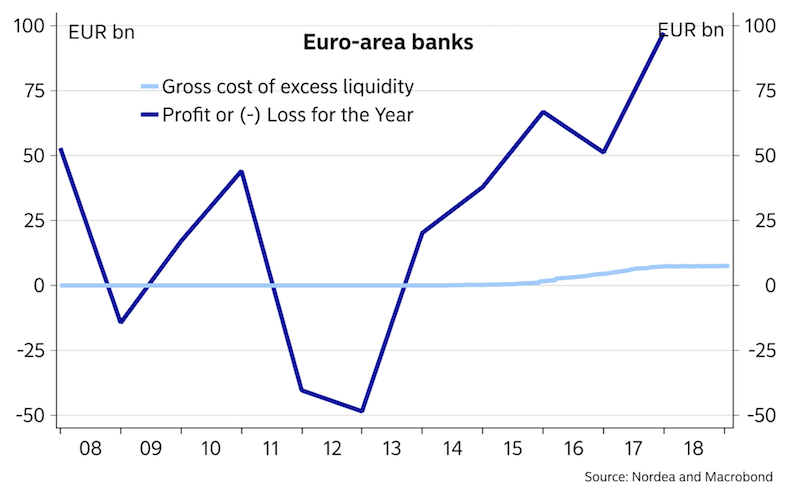

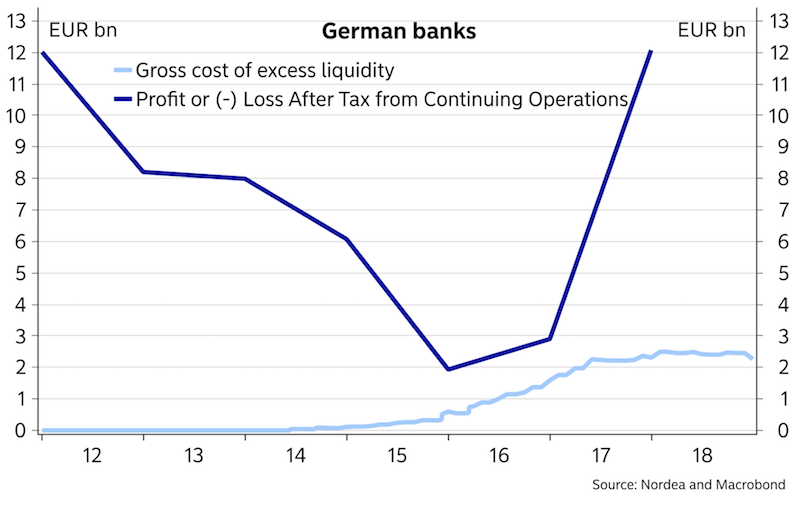

Negative rates and excess liquidity are a drag on bank profitability.

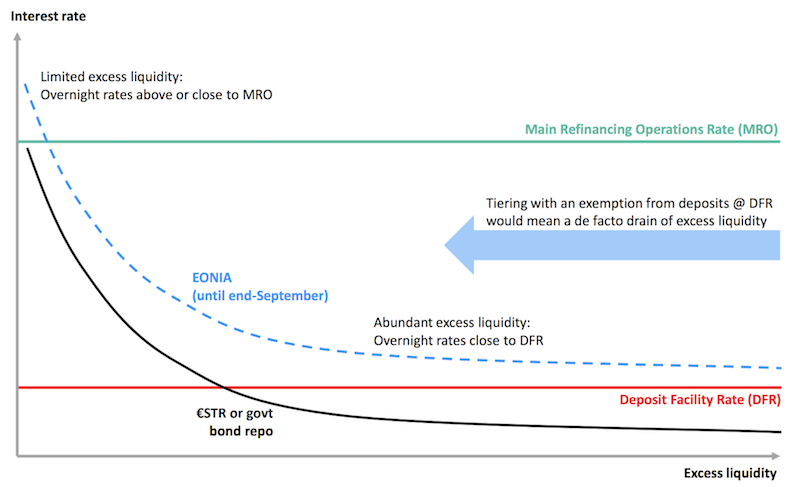

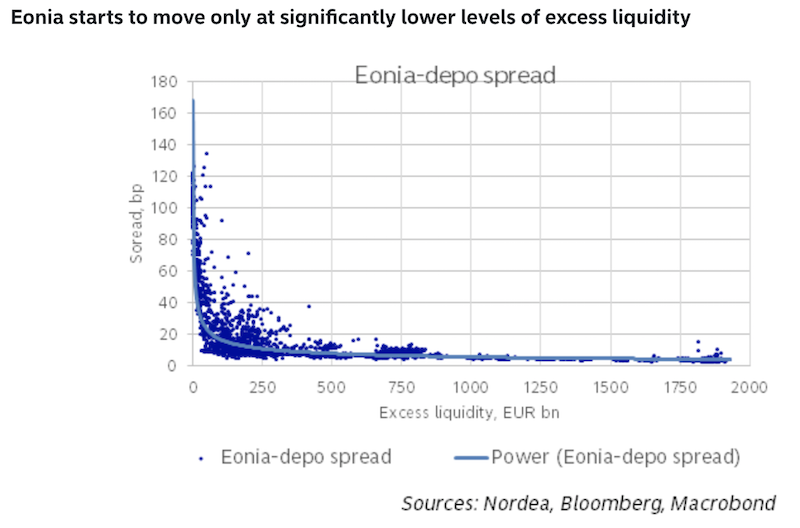

Excess liquidity means that banks are holding more in cash reserves than they should. Higher excess liquidity represents a general easing of monetary policy. Lower excess liquidity represents a general tightening of monetary policy. The effect is nonetheless highly non-linear. The lower the excess liquidity, the greater the impact on interest rates.

This is partially what the volatility in the US repo market was about in mid-September 2019. Excess liquidity in the banking system shrunk from money-market accounts being drawn down to fund quarterly tax payments that were due (on September 16 specifically). On that same day, an issuance of $78 billion worth of paper from the US federal government led to cash going from the commercial banking system (which buys the debt) into the US Treasury.

With respect to the euro system, the relationship between excess liquidity and short-term interest rates is shown below. Other parts of the chart – the main refinancing operations rate (MRO) and deposit facility rate (DFR) – will be covered later on in this article. The main idea is that as banks hold fewer cash reserves, this provides upward pressure on interest rates. This can have effects such as lower bond prices (higher yields), lower stock prices, and a higher euro currency.

A tiered interest rate system seeks to alleviate the negative impact on bank profitability by exempting some excess reserves from the effect of negative rates.

While this sounds good in theory, there are trade-offs like practically every economic decision and would come with its own risks and side effects.

In the ECB’s July 2019 meeting, policymakers wrote: “While members expressed broad agreement with initiating preparatory work on mitigating measures, some concerns were raised regarding possible unintended consequences of a tiered system and its ability to fully mitigate the potential effects of negative policy rates on bank intermediation.”

Nonetheless, if the euro area economy continues to underperform (e.g., Germany, the EA’s largest economy, is in a mild recession), a tiered interest rate system would be further implemented to ease monetary policy while aiming to spare banks from some of the adverse impact.

Tiered interest rate system represented graphically

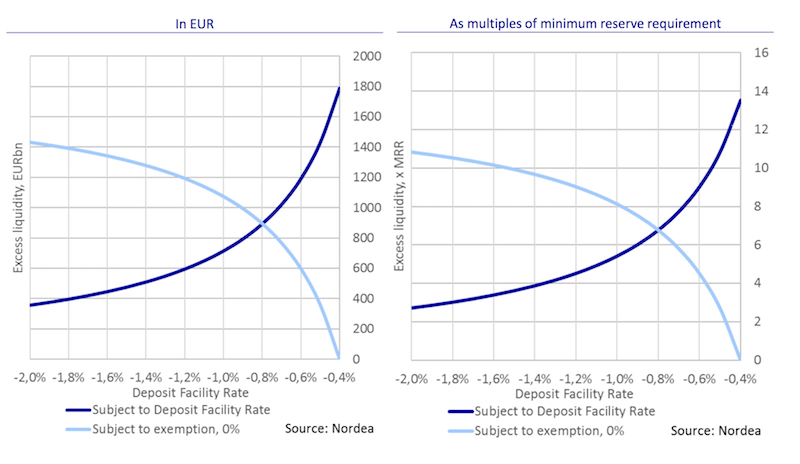

The general relationship between excess liquidity and deposits subject to the deposit facility rate and subject to exemption can be found in the left chart below. Excess liquidity expressed as multiples of the minimum reserve requirement is shown on the right.

The basic idea displayed in these charts is that, in a tiered interest rate system, it is important to get the balance right. When reserves are exempted, this lowers excess liquidity, which represents a tightening of monetary policy.

The key is to get the tiering system “correct” based on the convexity (non-linearity) in the relationship. Some level of exemption will help avoid bank disintermediation (a form of inadvertent monetary tightening due to the drag on credit creation) and do so at a benefit in excess of the tightening in policy.

However, at a point, the level of exemption will tighten policy in excess of the benefit to bank intermediation and would not represent an easing in conditions.

General Discussion

Negative interest rates have been a bone of contention among many central bankers and economists. By the traditional thinking, interest rates should not go below zero. When entering negative territory, that means, counterintuitively, you start paying borrowers to take on credit. Investing to get a negative return doesn’t make much traditional sense in terms of the incentives. It’s essentially backwards.

It is largely understood that cash and bond markets can only go so far into negative territory. There’s a certain limit regarding how low you can push rates to get investors into riskier assets and to get lenders and borrowers more likely to do business with each other at the margin. Negative rates make cash a little less attractive, but not much.

Savers will still be inclined to save and lenders and borrowers will still be prudently cautious with each other when the economy slows. By that reasoning, the effect of negative rates doesn’t have the same type of stimulatory influence on growth as it would if rates went down by the same amount when rates are positive.

During the financial crisis, the US did not go below the lower zero bound. Instead it stuck with lowering interest rates further out on the curve through the purchase of US Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. Price and yield are inversely related. Buying causes prices to go up and yields to decrease.

Back over a decade ago, the common belief was that lowering the reserve rate below zero wouldn’t have any influence on the deposit rate. If there’s no effect on the deposit rate, then there would be no stimulatory impact on banks’ funding costs. If there’s no lowering of banks’ funding costs, then there is no extra willingness for banks to lend. This means no extra stimulation to the credit creating capacity of the economy and no impact on aggregate demand and overall output.

Moreover, negative interest rates could actually be contractionary to the money- and credit-creating capacity of the banking system when factoring in the agency costs between banks and their creditors.

So, the US Federal Reserve decided to create reserves and purchased government credit securities.

In the future, monetary stimulus could include “helicopter money” where the Fed will issue currency and put it directly in the hands of consumers – skirting the financial system and bond market altogether – and tie it to spending incentives (such as having this money disappear if not spent before the end of a certain expiration period). But that’s a topic for a different day.

In Germany, negative interest rates have been controversial due to the strains they place on the banking sector and savers, most notably vocalized by Jens Weidmann.

The banking sector in particular has issues charging negative rates on their deposits. For corporate clients and institutions, the pass-through of negative rates has been mildly successful, but households have still largely been shielded from negative rates. Understandably, many will not deposit much with a bank if they are effectively penalized for doing so. Many individuals would simply prefer to remain “under-banked” or “unbanked” altogether.

To go along with negative interest rate policy (sometimes referred to as “NIRP”), excess liquidity in the financial system has swelled. Toward the end of 2014, excess liquidity in the euro area banking system was €100 billion. It is now €1,800 billion.

These are cash reserves that banks hoard and don’t go into the economy. Within the context of a closed banking system, excess liquidity will return to the European Central Bank in the form of “excess reserves” (reserves held beyond what is required in a regulatory sense) or through the ECB’s deposit facility.

The gross cost per year of this excess liquidity at the current deposit rate of minus-40bps (-0.40 percent) is approximately €7.5 billion (€1,800 billion multiplied by -0.40%). Costs to the system started in late 2015, and a bit earlier in countries like Germany.

The minimum reserve requirement is €132 billion and charged at the main refinancing operation rate (MRO), leaving a gross cost of zero. The €7.5 billion might seem like a small amount in comparison to the sheer size of the banking system on an asset basis. But it is not immaterial when comparing it to the euro area banking sector’s annual profits, which approximate €100 billion per year.

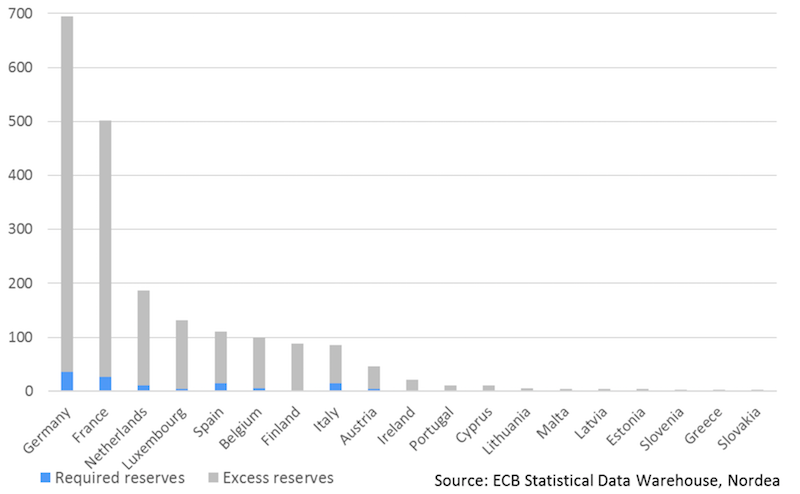

However, these effects are unevenly distributed among the euro zone. On top of that, there is no single risk-free sovereign bond or form of collateral in the EU. In Germany, the annual cost is more than €2 billion relative to bank profits of around €12 billion.

However, Germany’s share of excess liquidity is not particularly high in comparison to the euro area economy. Smaller countries like Luxembourg and Finland bear a much greater share of the excess reserves in relation to the size of their economies (speaking in terms of GDP).

In general, countries with low excess reserves need low rates and monetary stimulus the most.

The ECB has long had discussions about the negative impact on bank profitability. While bank profitability is not an explicit target of the ECB, it needs to be monitored.

Profitability impacts the amount of equity capital and thus banks’ capacity to lend.

It was a concern that was broadly known before the onset of NIRP policy back in 2014. Nonetheless, the ECB, under Draghi’s leadership, has argued that NIRP has been a successful policy choice.

Now that we are five years into ZIRP/NIRP, the effects of a protracted or perpetual stay at the zero (or under) lower bound is receiving increased focus.

However, the topic is complex. Some banks have been significantly impacted in terms of profitability by NIRP, while others have largely not been.

The implementation of €STR

The ECB has decided to implement what’s called the euro short-term rate (€STR) to make the tiering system possible and efficient. It will take effect on October 2, 2019 and undergo a testing phase between September 16-27, 2019.

It will reflect the wholesale euro unsecured overnight borrowing costs of banks located in the euro area.

EONIA fixings have been vulnerable to sudden jumps (not unlike the SOFR rate in the US, as compared to the more stable, but soon-to-be phased-out LIBOR rate due to its history of manipulation by traders).

The €STR’s higher turnover and trimming mechanism will help mitigate these risks inherent to the EONIA market.

Can a tiered interest rate system stimulate the EU economy?

Central banks are increasingly “out of ammo” in their ability to rectify languishing economic output.

When cash rates are at zero (or negative) that largely makes standard monetary policy ineffective. When spreads further out on the curve are at zero (or negative), then “monetary policy #2” is out of gas. So, within the toolkit of traditional monetary tools, if there’s a downturn, central banks may be left impotent in what they can do without new policy innovations.

Exempting excess reserves or part of excess reserves from negative rates can be one way to make rate cuts effective even when there is no traditional room left.

On a more micro, country-level scale we do have examples on which we can draw on empirically.

In Denmark, the central bank’s deposit rate is minus-75 bps. To avoid the punitive effect on bank profitability, negative rates were imposed on only a smaller amount of excess reserves. The complication is that effective interest rates could be higher than intended if excess liquidity is constricted too far. Denmark experienced this issue and eventually returned to 100% limits.

Based on empirical evidence within the euro area, the EONIA overnight rate tends to run higher once excess liquidity levels approximate less than €250 billion. At €1,800 billion in excess liquidity, this suggests that the ECB could safely exempt more than €1,000 billion in reserves without putting upward pressure on EONIA. (EONIA is the one-day “overnight” rate that banks lend to each other. It is similar to the fed funds rate controlled by the US Federal Reserve.)

It should be noted that using the past to inform the future is not always a sensible way to do things when the future is different from the past and new variables enter the system. The relationship between EONIA and excess liquidity is contingent on the relative heterogeneity (fragmentation) of the banking system.

However, we do know that excess liquidity would need to decrease materially before there was upward pressure on EONIA.

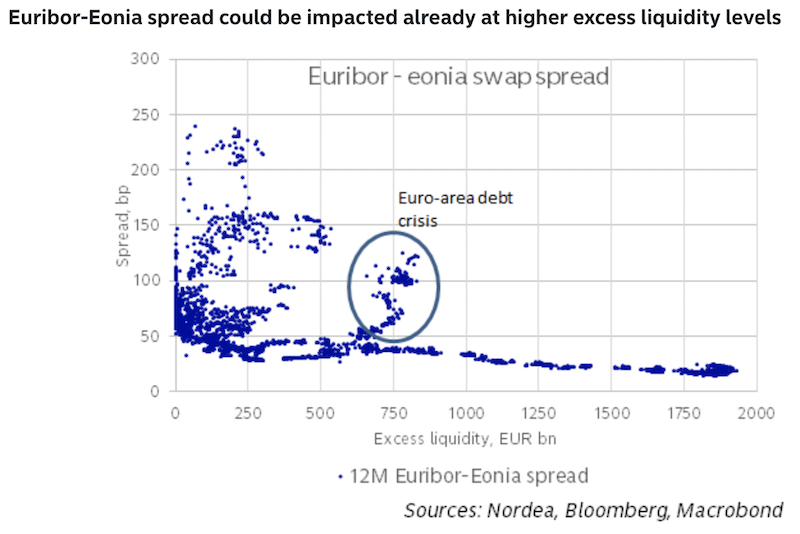

With that said, nothing happens in isolation. Even if excess liquidity is moving around at a level that doesn’t impact EONIA, it could still have influence further out on the yield curve.

It could also impact risk premiums in other asset markets – e.g., corporate credit, equities – and have an influence on the euro currency. Consequently, implementing a tiered interest rate system could have tangible consequences beyond a myopic focus on short-term rates.

The Euribor / EONIA spread had been impacted at much higher levels of excess liquidity in the past. This has notably occurred when problems were surfacing in underlying sovereign debt markets, which have flared up periodically since the 2008 financial crisis. The Euribor – EONIA swap spread ballooned outward at an excess liquidity of €750 billion.

Moreover, markets are a confidence game that discount future expectations and sentiment makes a difference in how markets behave. For example, in the US, the Fed’s balance sheet runoff, also known as quantitative tightening (QT), was largely responsible for impacting the downward plunge in equity markets in Q4 2018. Nonetheless, throughout that time, Treasury yields and Treasury risk premia were largely not impacted.

In other words, even if the ECB tries to make monetary policy more accommodative, a tiered interest rate system – which effectively takes away some of this easing effect – could be perceived as a de facto tightening of policy. This could spread to other asset classes, such as higher equity risk premia or a higher euro currency.

Challenges to a tiered interest rate system

Debate within the ECB on a tiered interest rate system is not new. The ECB first started this discussion when rates first ventured into negative territory.

The system was rejected by policymakers back then, partially due to the challenges in effectively communicating the policy to the public. Communication is important – both what to share and what not to share out of fear of over-sharing – as it helps guide households, corporations, and investors on the future path of monetary policy. This goes on to influence spending and other financial decisions that affect the economy and markets.

On September 12, 2019, the ECB announced the plan to begin the implementation of a tiered interest rate system in late October 2019. They announced a two-tier system that will aim to support bank-based transmission of monetary policy. Part of the excess liquidity holdings will be exempt from the negative deposit facility rate. This exempt tier will be remunerated at an annual rate of 0 percent.

The volume of reserve holdings in excess of minimum reserve requirements exempt from the deposit facility rate (i.e., “the exempt tier”) will be determined as a multiple of an institution’s minimum reserve requirements (MRR). This multiple will be the same for all institutions. For now, it is being set at six (6). If it were set lower, it could dry up all excess liquidity in countries like Italy and Portugal.

Around the time of the announcement, many sovereign debt rates in the EU bottomed and have gradually picked up since (effectively a tightening of policy), as the market was under-impressed with the ECB’s plan.

This goes back into the theme of communication being one of the primary challenges in a tiered interest rate system. Do traders take it at face value that it provides more room to cut rates? Or do they view it as ineffective in accomplishing its purported objectives?

What effect will it have on the transmission of monetary policy? Given it exempts certain amounts of reserves from negative remuneration rates, it will, in some part, reduce the influence of negative interest rates contributing to the easing of monetary policy.

Commercial banks have been trying for years to pass off negative interest rates to their customers. A tiered interest rate system would throw an additional wrinkle into this process.

Examples

Consider some hypotheticals using the following assumptions:

1. Each country’s banking system is treated as one single bank. In other words, it ignores fragmentation and assumes perfect homogeneity within countries’ banking systems.

2. Assumes that cross border transactions are negligible.

+++++

– Let’s assume an ECB rate cut to -60bps

– Exemption of 4.5x MRR would keep banks’ funding costs unchanged

– Under this system, excess liquidity might completely go to zero in Portugal and Italy

– In other words, banks would deposit at zero with their central banks instead of investment in their own short-term government debt or repos

– This would increase local short-term and repo rates back toward zero

– This would result in an unintended monetary tightening rather than an actual easing of policy (i.e., it backfires)

– Lesson: countries with lower levels of bank reserves are generally most in need of easing

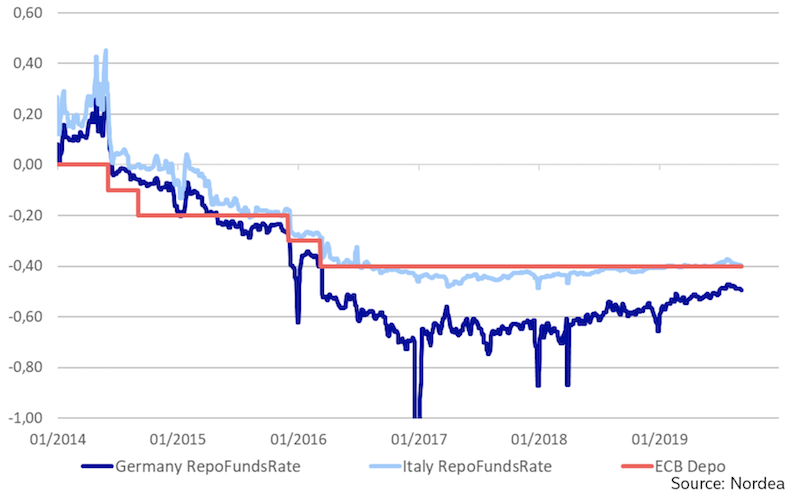

For example, let’s look at Italy’s repo funds rate relative to Germany’s. This is an influence of lower excess liquidity. Constrained supply lifts the rate higher.

+++++

Let’s say:

– ECB rate cut to -60bps

– Tiering of MRR + 5x MRR for excess reserves

– Beyond that, an exemption of 6xMRR would keep banks’ costs unchanged in this particular example

– Government bond repo rates would run close to the deposit facility rate

– Outcomes: (1) Excess liquidity would likely be maintained in each euro area country, including Italy and Portugal. (2) However, periphery banks (e.g., Italy, Portugal) would not benefit from a tiered interest rate system and would disproportionately favor countries in the northern part of the continent.

Where a tiered interest rate system is most likely to work

If the goals and implications of the system are not effectively communicated a tiered interest rate system could easily backfire.

Based on both theory and empirical evidence, a tiered interest rate system would work best in smaller countries with less fragmented banking systems and an explicit exchange rate target.

Denmark is one such example. Relative to the euro area more broadly, the banking system is less homogenized. But even then, Denmark’s central bank had to roll back its level of exemption when it was merely contributing to an unwanted tightening in policy.

A tiered interest system can also be a risky proposition when there is less clarity about the path of excess liquidity moving forward.

There is some demand for the ECB’s TLTRO program, which attempts to offer longer-term funding arrangements to banks that need it.

TLTROs are targeted operations. The amount that banks can borrow is contingent on their loans to households (with the exception of house purchases) and non-financial corporations.

The idea behind TLTRO is to create better autonomy in the monetary conditions of countries that are inherently linked together through the euro. However, the TLTRO III program launched in March 2019 is largely a rollover of existing financing arrangements. Moreover, nothing is better at gaining autonomy over one’s own monetary policy by being able to control the currency. Since many different economies in the euro zone share the same currency, they are all functionally linked together in a pegged system.

Excess liquidity may also fall in the coming years. Introducing a new variable into the euro area’s monetary system (tiering) while excess liquidity is falling will add a new level of uncertainty and could undermine confidence. Moreover, decreasing excess liquidity also has the effect of reducing the impact of negative interest rates on banks.

But the longer negative rates go on – and it will be a while with productivity, labor growth, and inflation as low as they are – the more likely tiering, in terms of its scope and extent, becomes likely.

Loosening monetary policy is in the ECB’s interest and a tiered interest rate system is the way they will primarily approach the task in addition to a resumption of asset purchases.

On the topic of TLTRO within a tiered interest rate system

Within a tiered interest rate system, there comes the potential for banks to engage in TLTRO arbitrage.

Banks could receive inexpensive TLTRO funds from the ECB, then turn around and deposit them at a higher rate with the Eurosystem. (The Eurosystem comprises the ECB and member state national banks that use the euro as their currency.)

In order to preempt banks from taking advantage of these arbitrage opportunities, funds available through the TLTRO program should not be eligible for exemption in a tiered interest rate system. There are currently about €700 billion of TLTROs outstanding.

Spanish and Italian banks most actively use TLTRO funds. Accordingly, if TLTRO funds are excluded from a tiered system, then banks in these countries are unlikely to benefit from deposit exemptions. Excess liquidity would remain high and keep repo and short-term money-market rates low.

The case of Denmark

Denmark’s main monetary policy objective is to maintain stability in its currency – namely it aims to keep the EUR/DKK rate somewhere within a band. This is accomplished by keeping policy in line with the ECB’s.

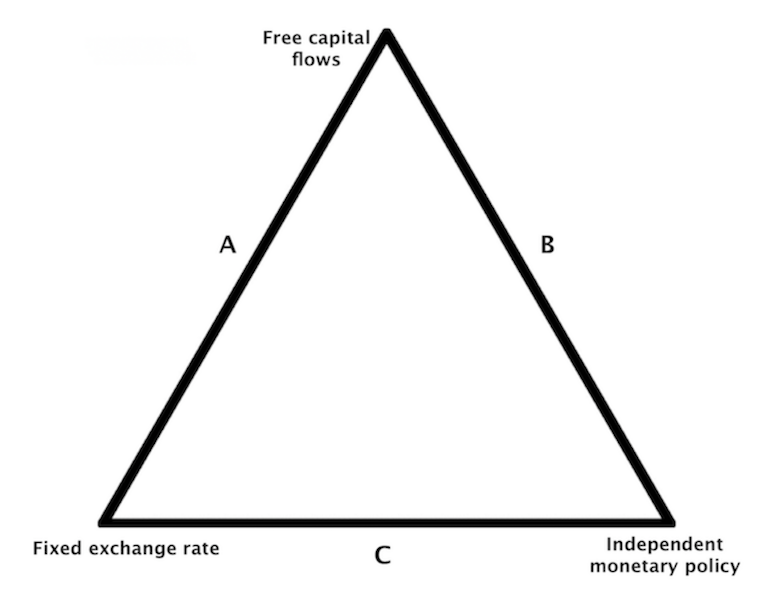

We know from the “trilemma” phenomenon as it pertains to currency regimes that in order to maintain a fixed exchange rate while keeping its capital account open, a country must forgo having an independent monetary policy.

In other words, Denmark has chosen side A of the triangle below.

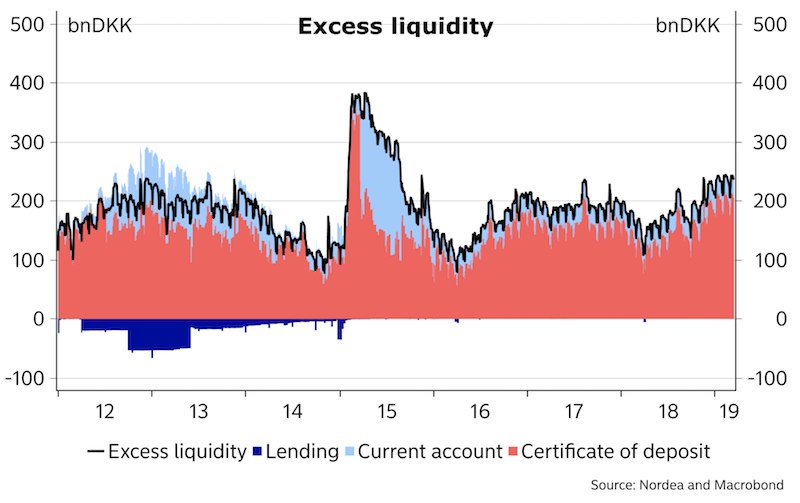

Denmark’s monetary system is characterized by large excess liquidity relative to its GDP, or about DKK250 billion (approximately €35 billion).

Banks hold more cash reserves than what might be optimal. Accordingly, adjustment of deposit rates is the central bank’s main way of carrying out monetary policy.

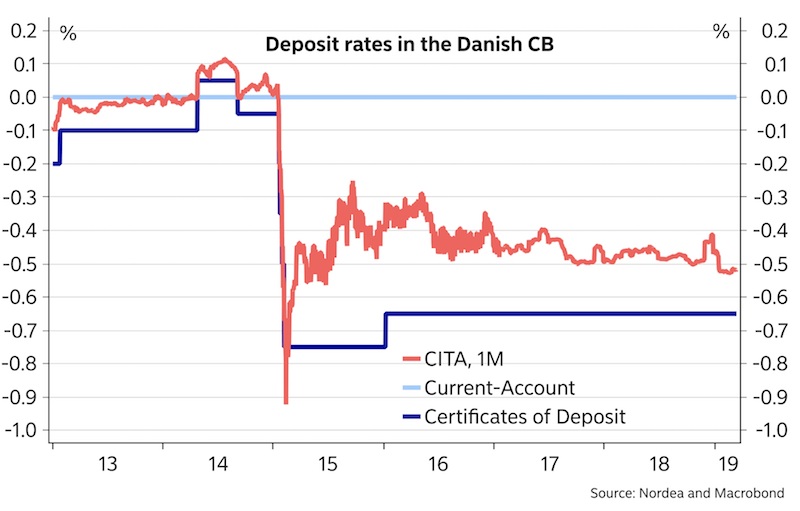

The Danish central bank has divided the deposit facility into a two-tier system. The main facility is the purchase of certificates of deposit issued by the central bank at minus-75 bps. As a supplement, there is the current account deposit facility where banks and other monetary policy counterparties can make overnight deposits. This is set at zero percent.

Denmark’s central bank has also set a limit on current account deposits. This works to keep short-term money market rates at the desired spread relative to euro rates and prevent a buildup of deposits that could be used to exert speculative pressure against the de facto currency peg kept with the euro.

The CITA rate, used in Denmark as the reference rate for various lending agreements and credit securities, is kept in between the deposit rate and facility rate.

Advantage of a tiered interest rate system

With respect to a basic two-tier system there are several advantages.

1) It increases a central bank’s capacity to lower rates below zero while minimizing the impact on lending profitability in the financial sector.

In an economy like Denmark, the increased flexibility provided by a tiered system when at the lower zero bound rate helps preserve credibility that it can defend its currency peg to the euro without having to resort to other means (controlling the inflow and outflow of capital from DKK to other currencies).

2) Monetary policy can be flexibly adjusted as needed within a multi-tier system. When Denmark’s central bank needed to go below zero on the certificate of deposit rate back in 2012 (i.e., the facility rate), they maintained the current account rate at zero and increased the current account limits by more than 300 percent. This helped to minimize the spillover effects of negative interest rate policy on the financial sector, and particularly at a point when negative rates were new policy and its adverse knock-on effects weren’t broadly known.

Conclusion

Given productivity, labor growth, and inflation are languishing, the expectation of very low rates in the euro area are the forecast for a long time. Some assumed that rates would “normalize” simply because they’ve been higher in the past.

It’s natural to extrapolate the past, but the present and future are different from prior economic scenarios. Currently, the “3 D’s” are keeping rates low:

- demographics (aging throughout the developed world limiting labor market growth and straining pension and healthcare obligations),

- debt (more income goes toward debt servicing rather than seeing it spent in the real economy), and,

- disinflation from technological innovation (pricing is more competitive among platforms, valuable information is increasingly free, and so forth)

Nominal rates must follow the trend in nominal growth. Specifically, debt servicing costs must be kept below the rate of income growth, otherwise this will eventually lead to debt problems. This can be done by lowering interest rates. Central banks traditionally have a lot of control over this process.

This might mean negative interest rates. However, negative interest rate policy can induce bank disintermediation (difficult for banks to produce net income). When this occurs, banks become reluctant to lend, which can lead to sub-optimal levels of credit creation. Thus, negative interest rates, an intended form of monetary easing, can induce the opposite effect.

Yet, central banks want to have their cake and eat it too. Hence the idea of a tiered interest rate system to alleviate these potential effects.

An inefficiently designed tiering deposit system could result in an unintended tightening of monetary policy. Or it may result in higher market rates in countries with low bank reserves.

After all, if you exempt certain reserves from the lower rates, that means they’re remunerated at a higher rate. That’s a tightening measure in some form.

The arbitrage opportunities that banks will engage in with respect to TLTRO funds create further difficulties.

Ideally, the ECB could have approached the situation by introducing a tiered interest rate system first and cutting rates down the road to manipulate just one variable at a time. This would give an observation period. However, the ECB needed to sufficiently ease policy in September and accordingly did both.