Carbon Emissions Trading – Exploring the Carbon Market

Carbon emissions trading is a type of policy that enables companies to buy or sell allotments of carbon dioxide (CO2) output permitted by governments with regional or national emissions standards.

Carbon emissions trading is based on the idea that individuals or institutions can each own, buy or sell permits to produce greenhouse gas.

Carbon emission permit trading allows companies to manage their carbon output by either reducing it, offsetting it, or buying allowances to exceed it.

This helps reduce costs for businesses because they can meet their reduction obligations more cheaply through buying additional credits rather than reducing their own pollution levels.

During an initial period of allowance distribution, this market is made with a fixed amount of credits available for purchase (known as initial allocation).

Once this is established and the free market takes over, prices change in response to supply and demand, like other markets.

Because of the reduced supply and increasing demand for emissions allowances in a carbon emissions trading scheme, some economic studies have shown that the price per unit of carbon must increase in order for society as a whole to benefit from reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon emissions permit trading, in this case, becomes a new valuable commodity.

Carbon emissions trading is based on the idea that individuals, institutions, companies, and other organizations can each own, buy or sell permits to produce an acceptable amount of greenhouse gas – to support industrialization and economic activity (e.g., power plants or transportation to allow them to continue producing with little effect on industrial output (such as power generation)).

Carbon emission permit trading enables companies to manage their carbon output by either shrinking it, offsetting it, or purchasing allowances to exceed it as a way to pay for the negative externalities associated with activities that cause pollution.

Carbon taxes and energy prices

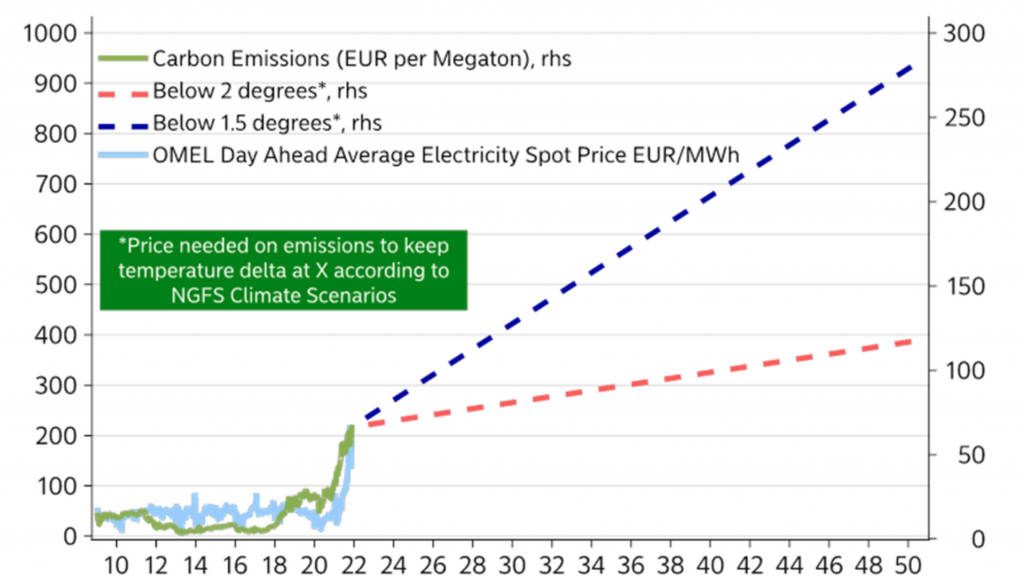

There is a strong correlation between the price of carbon emissions and electricity. (Electricity production is responsible for around 20-25 percent of all global emissions.)

If policymakers intend to pursue a path of keeping the temperature increase below 1.5 degrees Celsius before 2050, then households may see a rise in energy prices.

Carbon taxes act as taxes on carbon emissions implemented by nations, states, regions, or other municipalities.

Some countries have adopted either a tax on the carbon content of energy or a wide-reaching tax that uses carbon intensity as one criteria among others.

Carbon taxes vs. carbon trading

Carbon taxes are commonly viewed by economists to be the most economically efficient way to curtail the rise of or reduce carbon emissions (either outright or on a per-capita basis).

Carbon taxes disincentivize carbon-intensive activities and create incentives to seek alternatives.

On the other hand, carbon emissions trading is a market-based approach to the issues that sets an upper limit or cap on total carbon emissions.

Carbon taxes are set by the government as a matter of public policy. But carbon trading is based on supply and demand forces in the market (that are a result of climate policy and other carbon management practices).

A carbon tax can be used at different levels of government (city, state/province, central/federal) to reduce carbon emissions. Carbon trading schemes have been implemented at only the country-level.

The Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition brings together both government and private sector participants, and lists 18 countries that have greenhouse gas pricing policies that meet their criteria for “leading” carbon pricing. These nations include Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Mexico, Morocco, Norway, South Korea, Russia, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Carbon emissions permit trading, in this case, essentially creates a commodity that can be bought or sold for those with access to the open market.

Carbon emissions permit trading is an alternative method of regulating carbon emissions, and enables member countries to trade emission rights of carbon (or carbon dioxide) without having to rely on their own domestic regulations – even though carbon allowance prices are often impacted by regulations since allowance demand has many different sources.

Carbon emissions trading does not require government action, which makes it a cost-effective method of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon permits are established by public policy with prices then determined by free-market supply and demand.

Every country has several different sources and a unique mix of carbon emissions (e.g., electricity, transportation, construction, agricultural practices). As a result, carbon pollution levels to meet GHG reduction targets vary depending on the country’s economy and its makeup.

Carbon emission trading schemes gives countries like China a chance to reduce its GHG emissions without having an acute trade-off between the environment and economic growth (since they produce a large and increasing amount of global emissions).

Carbon taxes can work as an incentive for governments to regulate industries that create high quantities of carbon emissions.

Carbon taxes are more effective at reducing GHG emissions if they are higher than the price on an equivalent amount of carbon offset credits.

Carbon offsets allow industries with high levels of carbon emissions to remain profitable, but it may come at the cost of higher-priced products until renewable energy sources can more capably fill in a greater portion of demand.

The basic goal of many carbon trading programs was to let everyone compete under the same rules rather than placing limits just on large carbon producers.

Pricing of carbon emissions and electricity needs to rise massively to keep temperatures at bay

(Source: Nordea, Macrobond)

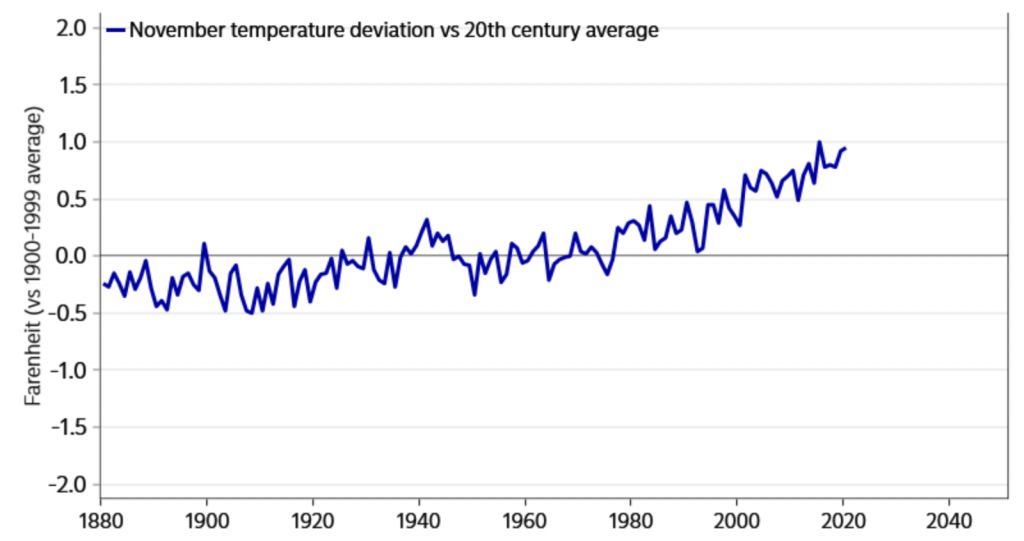

Global temperature deviations in November vs 20th century average

(Source: NOAA, Nordea, Macrobond)

To reduce climate change, many governments globally have tried to reduce supply of cheap brown energy. However, the demand for energy is still the demand.

If supply is constrained and new alternatives aren’t available, then the price goes up.

Global infrastructure is still highly dependent on brown energy. When lots of new building is needed and demand exceeds the supply, this is inflationary.

There is some acknowledgement of this in policymaking circles. More governments want their central bank active in climate policy – even though its dubious how much that type of institution can actually do on that front.

A central bank’s mandate is typically either inflation or output and inflation (and either de facto or in practice, matters related to the national currency and financial stability).

Sweden’s Riksbank’s Governor Ingves argued that ESG/environmental-induced inflation may essentially be ignored as it pertains to monetary policy.

In other words, some policymakers are of the mindset that climate matters are important to the point where any excessive pricing effects from it will be excluded when making policy decisions.

Greenhouse gas emissions as a new commodity

Parties that have commitments under the Kyoto Protocol (Annex B Parties) have accepted targets for limiting or reducing their carbon emissions.

These targets are expressed as allowed emissions levels.

Allowed emissions are divided into assigned amount units, known as AAUs.

As explained in Article 17 of the Kyoto Protocol, emissions trading allows countries that possess spare emission units – emissions permitted to them but not used through industrial or other economic activity – to sell this excess capacity to other countries that are over their targets.

It’s effectively a form of cap and trade. This is a system for curbing carbon emissions and other forms of pollution for which an upper threshold is set on the amount a given business or other organization may produce, but allows additional emissions capacity to be bought from other organizations that have not used their entire allowance.

With carbon, a new commodity was effectively created in the form of reducing emissions of it. Since carbon dioxide (CO2) is the principal greenhouse gas, this is often talked about as “trading in carbon”.

Carbon is thus tracked and traded like any other commodity. This is known as the “carbon market”.

Other trading units in the carbon market

More than actual emissions units can be traded and transacted in under the Kyoto Protocols emissions trading program.

The other units that may be traded under the program may be in the form of:

- An emission reduction unit (ERU) generated by a joint implementation project

- A removal unit (RMU) on the basis of land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) activities (e.g., reforestation, linked back to savings in CO2 equivalent emissions)

- A certified emission reduction (CER) generated from a clean development mechanism project activity

Each unit is equal to one ton of carbon dioxide.

Transfers and acquisitions of ERUs, RMUs, and CERs are tracked and recorded via the registry systems paid out under the Kyoto Protocol.

An international transaction log works to make sure that emission reduction units are securely transferred between countries.

Commitment period reserve

Because of the potential for some entities to essentially “oversell” their units to the point they aren’t able to meet their own emissions targets, it’s required that each entity has a reserve of ERUs, CERs, AAUs, and/or RMUs in its national registry.

This reserve is called the “commitment period reserve” should not drop below either:

- 90 percent of the Party’s assigned amount or

- 100 percent of five times its reviewed inventory as of its last review, whichever is lower.

Relationship to domestic and regional emissions trading schemes

Emissions trading schemes can be established as climate policy implementations at the regional and national level.

Under these programs, governments set emissions targets and obligations that should be reached by all entities involved. The European Union emissions trading scheme is the largest ongoing operation.

The implementation of the Kyoto Protocol’s emissions trading program is also an example of a regional emissions trading scheme.

Australia’s Carbon Pricing Mechanism (CPM) is a form of emissions trading system designed by its government. The Australian CPM helped Australia become the first country in the world to have a carbon pricing mechanism operating at both the state and federal level.

The design specifications of the program are similar to those that were adopted by the state of California.

Struggles of the carbon credits market

When stocks started to tumble in 2022, the booming market for carbon credits fell too.

Speculators cashed out on bets that demand from companies looking to reduce their emissions would keep prices rising.

The average price for carbon credits got up to $13.10 in February 2022, according to the energy-data firm OPIS.

But in March, as surging energy prices increased the threat of recession (due to how many countries have to import energy) and inflation rose, prices fell to an average of $8.17, based on OPIS data.

Carbon credits are used by companies seeking to effectively offset their greenhouse-gas emissions.

The credits fund projects that lower carbon in the atmosphere or avoid emitting additional carbon, such as preserving forests or planting trees or funding renewable energy and power projects.

Thousands of companies have pledged to reduce their emissions, potentially creating large demand for the credits.

Lots of hot money came in at a faster rate than end-user demand, and a lot of speculatives chasing carbon credits as a hot asset either wanted to realize a profit or fold their bets.

There were reasons for the downturn other than rising interest rates.

Oil and gas traders had much larger carbon-trading desks in preparation for a 2021 United Nations climate conference where world leaders agreed on broad guidelines on how countries and companies can trade credits internationally.

Higher interest rates made their leveraged trades in the market less profitable. A lots of new credits hit the market as prices rose, creating a supply-driven slump in the market as well.

The downturn was unexpected among many traders because the carbon market hasn’t historically correlated with equities.

When it did move, the more speculative or lower-quality credits fell the hardest, just as riskier stocks typically drop to a greater extent when the overall market declines.

Conclusion

Carbon emissions trading (also known as carbon offsetting) puts a price on the cost of carbon (CO2) emissions produced when burning energy materials such as coal or oil.

Carbon permits can be traded between companies or individuals in systems that cap their total carbon output or those with no upper limits on the amount of allowable carbon output.

It is one method for countries or organizations to control their carbon dioxide emissions. Carbon offsets are measured and verified reductions in carbon emissions that are achieved by funding projects that decrease, offset, or avoid CO2 and other GHG emissions elsewhere.

The carbon market is an emerging market that has relatively recently been put into effect. There are several factors that need to be considered when entering the carbon market, including the countries economy and how it relates to carbon emissions.

Many nations established carbon emissions targets for (since-passed) 2020 and others may not even have any until 2030 or 2040, but they can become part of the carbon market at any point.

A country could save money by buying carbon credits from another country with few climate obligations, like India, which has a GDP growth rate significantly higher than many European and other developed nations due to their rapid industrialization process (similar to China) and essentially playing catch-up with the rest of the world.

The carbon market could potentially significantly increase from a relatively modest $40 billion (in annual trading). But it’s subject to change depending on the carbon market’s legal status in different nations (China, India, etc.) and future legislation.

But carbon emissions trading is here to stay. Carbon credits are already an established commodity instrument for carbon offsetting and it’s only a matter of time before carbon markets become more mainstream financial instruments. There already exists things like carbon derivatives, which are traded in many types of financial instruments.

The closest way a retail trader could get direct access to the carbon market is through a CFD.

The value of carbon credits depends on the demand for them. With where carbon emissions likely need to go to prevent temperatures from rising by 1.5-2.0 C by mid-century, their value is likely to increase.

Carbon trading allows companies and organizations to trade with each other to buy and sell credits instead of reducing their own emissions, which provides a way of conducting business when reductions and net zero goals are unattainable in the short term.

Carbon emission trading has the potential to stabilize carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions, create sustainable financial markets, and set new standards for environmental awareness. Carbon reductions are likely needed by the majority of nations in order to meet collective emissions goals.

Carbon markets can also be used to incentivize more creation of renewable energy sources. Carbon trading creates a price on carbon that can encourage businesses and individuals to plan for their future by enabling them to prepare for the costs of carbon pricing.