Turkey’s Currency Crisis of 2021

Turkey’s central bank cut rates by 100bps in November 2021, which was expected by the market and Bloomberg consensus. However, given Turkey’s economics fundamentals, the rates cuts were not necessary, leading the country to another currency crisis.

Why did markets throw a tantrum?

They didn’t want the CBRT (Turkey’s central bank) to cut and sold Lira ahead of the meeting to indicate their belief in a policy error.

CBRT didn’t listen to market signals and cut anyway.

In total, this put the Lira down over 20 percent in less than two months.

It’s an enormous move for a national currency and easily the worst performer in emerging markets.

Turkey’s currency crisis could weaken President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s nearly two-decade grip on power and worsen living standards.

The depreciating Lira is a self-inflicted wound for Erdogan, who has pushed for lower interest rates as part of an unconventional economic strategy that he argues will encourage growth. This rate cut was the third in three months.

Lower interest rates will push up the inflation rate, as it makes borrowing and credit creation easier.

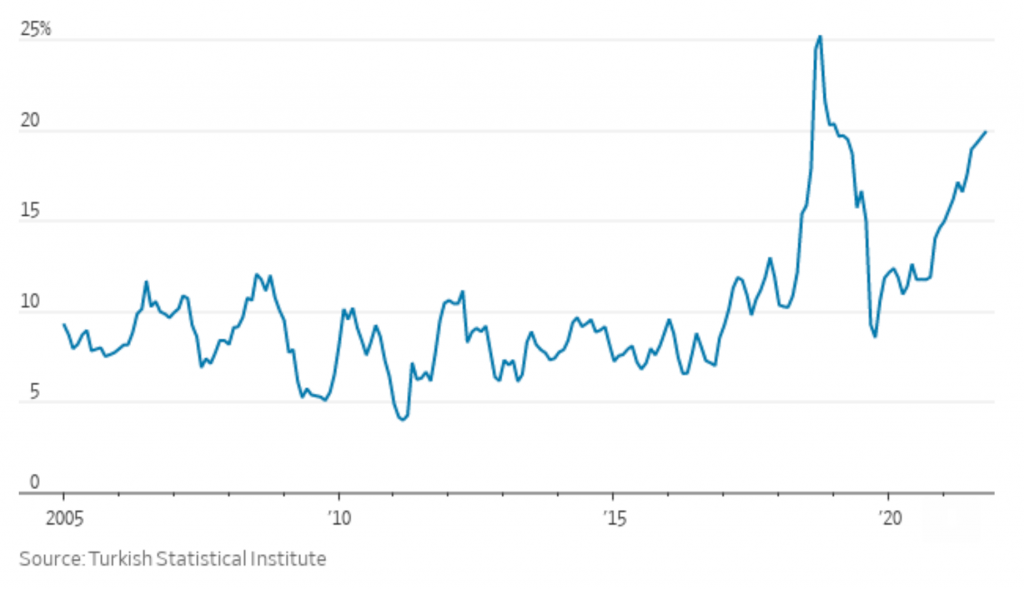

Turkey’s CPI index

Why was Turkey’s rate cut a policy mistake?

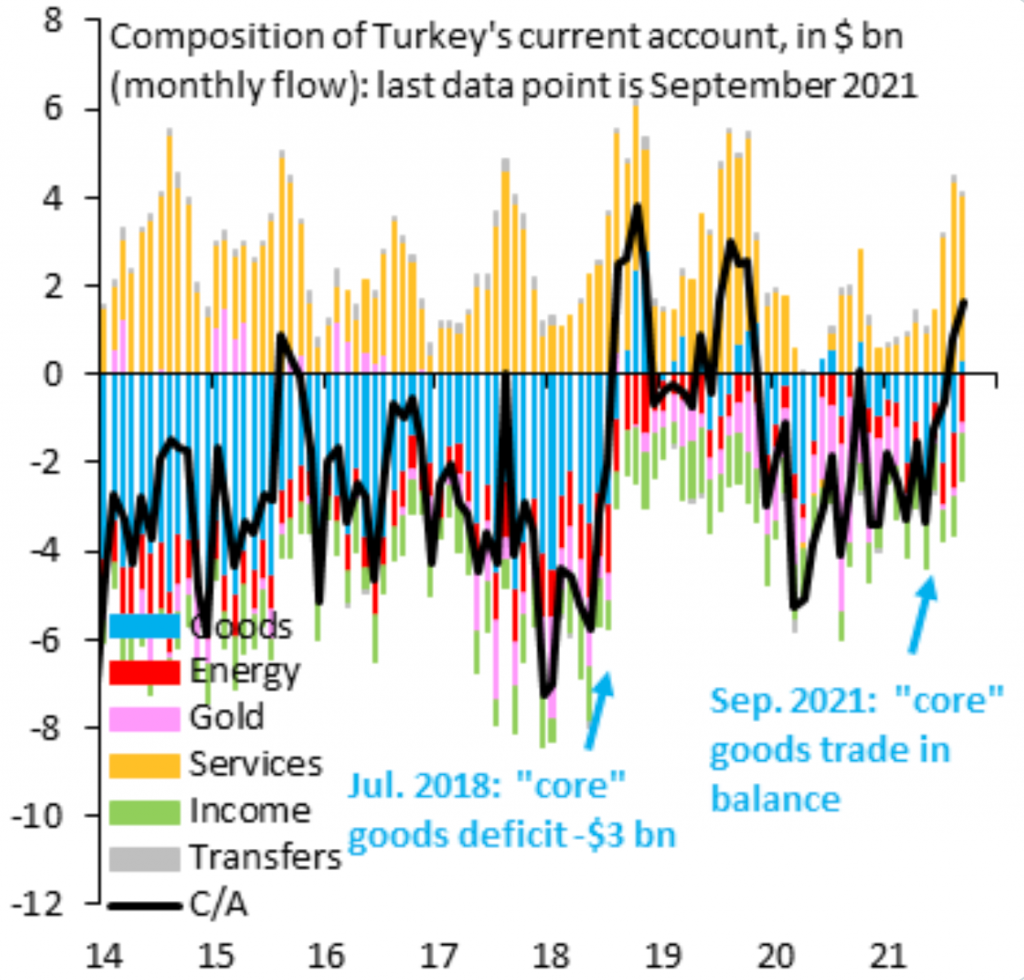

In July 2018, just before the balance of payments “sudden stop” (in capital flows) that caused Lira to fall sharply, Turkey’s “core” trade balance was minus-$3 billion (blue).

In the latest data leading up to Turkey’s policy decision, this “core” goods balance was in slight surplus. Its balance of payments fundamentals don’t warrant Lira falling further.

(Source: IIF)

In most countries, the central bank is independent from the central government.

This way, a central bank won’t be inclined to bend to political whims.

With Turkey’s high inflation rate and otherwise solid balance of payments fundamentals, they need rate hikes, not rate cuts. At the least, they could have stayed on hold.

Their trade deficit was already fine before this latest currency collapse even though oil prices are high (Turkey is an oil importer and therefore higher oil hurts its balance of payments).

With this latest fall, Turkey will see a big drop in imports and push the trade deficit even lower and support currency appreciation.

It looks a lot like the sudden stop in August 2018. But back then it was about geopolitics. This time it’s a form of self-sabotage with the unnecessary and counterproductive rate cuts. Lira was already undervalued.

The more violent sudden stops are, the faster they end and reverse.

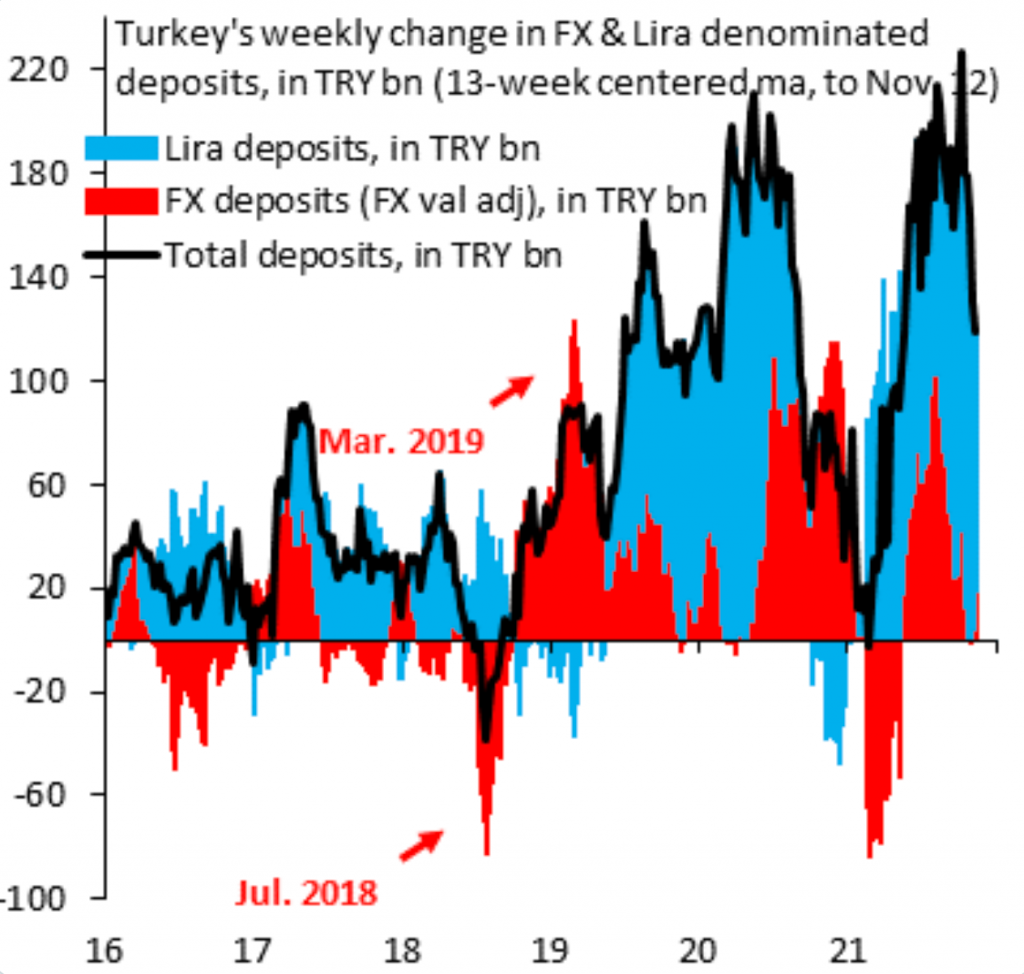

Will Turkey dollarize?

When a currency is undergoing depreciation pressures and/or there’s a lack of currency stability, people often want to exchange domestic currency for something more stable.

That often means a reserve currency.

Traditionally, in Turkey, where there’s a history of inflation and poor currency stability, people move their currency into USD and EUR.

This helps them retain more purchasing power even though they’re subject to the whims of exchange rate fluctuations.

About 60 percent of all domestic deposits are in foreign currency.

So, there are lots of rumors about dollarization in Turkey, but no real-time data.

We nonetheless know what happened in 2018 during the big Lira fall. Back then there was no dollarization as a result of any panic that the country’s currency could continue sliding. In fact, it was the opposite; flows into FX deposits were negative. There won’t be much dollarization now either.

The Lira’s rapid slide resulted in some Turks exchanging their liras for dollars, euros, and other currency. About 59 percent of retail bank deposits are now in foreign currencies, up from nearly 57 percent the week before.

(Source: IIF)

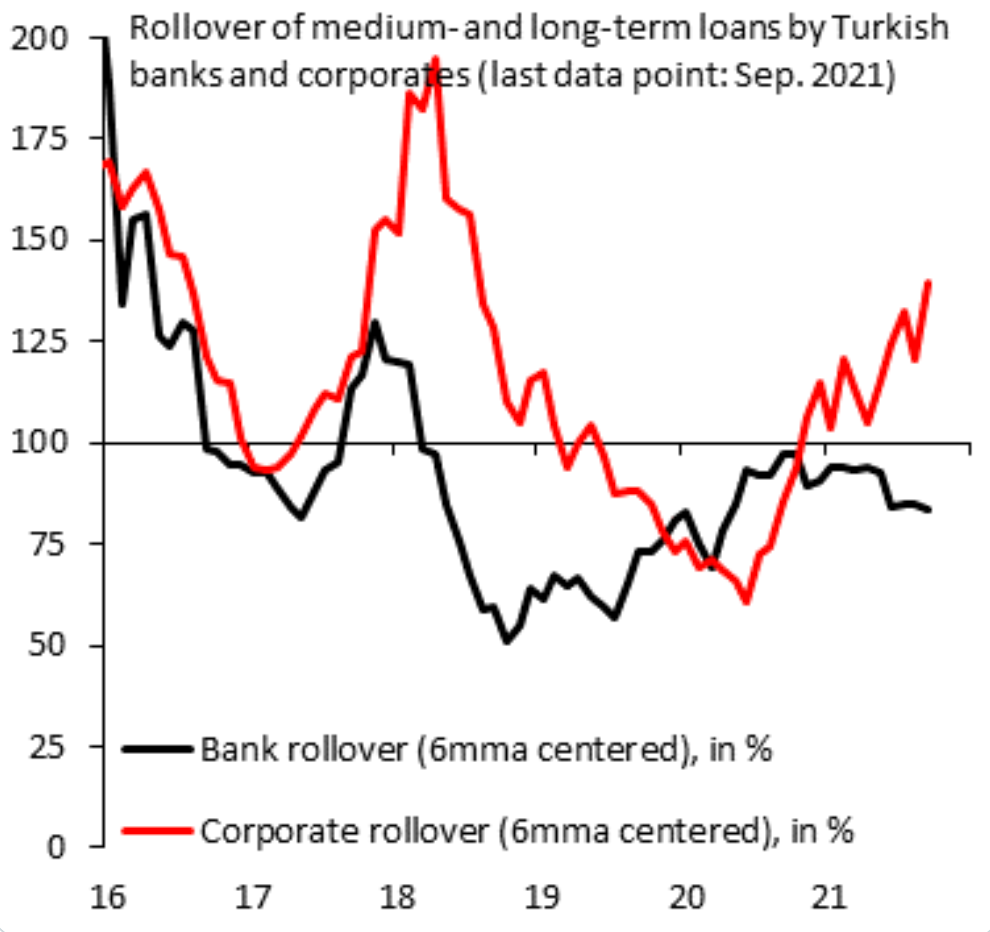

Will currency depreciation endanger corporate and financial stability?

When the Turkish Lira falls sharply, as is the case now, there’s naturally the question of whether this poses risks for the corporate sector and financial stability.

The currency depreciation pressure will be somewhat of a negative on Turkish corporates that took out long-term foreign currency loans. However, if they can rollover their debt, then there’s no problem. Currency depreciation can actually help because it reduces the cost of repaying these loans in Lira terms.

But if they can’t rollover their borrowings (because there’s a sudden stop in capital flows), things get much worse because they often can’t repay their debts, especially if they’re overleveraged and don’t have the reserves or income.

However, Turkish corporates have been able to rollover their foreign currency debt with ease for years now.

This is because Turkey has become an increasingly attractive emerging market destination for yield-seeking investors (despite all the political risks and turbulence it faces) – which created a place where “carry” trades were popular.

Turkey traditionally has among the highest yields in emerging markets. Of course, a lot of this yield is simply because inflation is traditionally quite high.

But for foreign investors, you aren’t subject to that inflation rate like domestic investors – you care about the currency movement relative to your base currency.

In other words, as long as you get an interest rate that at least compensates you for any expected depreciation you have what’s called positive carry.

This won’t change now given Turkey’s favorable balance of payments. Turkey will remain an attractive place for yield-seekers relative to other emerging markets, despite the fall in Lira.

The main difference is that inflows will be more volatile and less predictable than they were before because of the political interference in how policy is run.

A key consideration in trading macro themes is whether policymakers are:

a) knowledgeable enough to do the right things, and

b) have the power to do so

When politicians have a large hand in this process and overreach because of short-term political goals or because they’re misguided on what they think is best, and their authority overrides those who might otherwise be knowledgeable on the appropriate steps, then missteps can happen.

This can include unfavorable outcomes like excessive currency depreciations, higher inflation, and lower growth.

If Turkish banks are vulnerable, then central banks would need to set rates high enough to slow growth, just to calm currency depreciation.

But there’s no risk of financial instability so long as the current account remains in surplus and inflation doesn’t get much worse.

But generally speaking, will corporates have issues? The answer is no. They’ll be able to rollover their loans just fine.

Lira devaluation in August 2018 was much larger and Turkish corporations managed well. They will manage just fine again now.

(Source: IIF)

Turkey’s central bank said the country’s banking sector remained robust and had sufficient liquid assets to withstand the currency crisis, taking some pressure off Erdogan to change course on economic policies.

As a political maneuver, Erdogan ordered an investigation into potential currency manipulation, tasking the State Supervisory Council to identify institutions that bought large amounts of foreign currency to determine whether any manipulation had occurred.

Mechanics of a currency depreciation

Turkey faced a combination of high inflation and sound balance of payments fundamentals.

That combination favors interest rate hikes.

This would slow credit creation to rein in inflation. At the same time, with a current account surplus, there is no need for more exports and fewer imports.

(A cheaper currency stimulates exports because the goods are cheaper for other countries. It also makes imports more expensive because a weaker currency can’t buy as much.)

If Turkey was facing a different combination – such as high inflation and a balance of payments deficit, or low inflation and a BoP surplus – then the trade-offs are something to consider.

It depends on the balance between the two – i.e., which is better and which is worse?

For example, if the high inflation component is worse than the balance of payments deficit, then rate hikes would still be favored. If they roughly match up, then policy might be in a favorable place monetarily, though specific actions can be taken (e.g., through fiscal policy or macroprudential tools) to rectify issues in certain areas.

However, in this case, the decision was black-and-white. Turkey’s fundamentals favor higher interest rates.

Doing the polar opposite of this – cutting by a full percentage point caused the currency to drop. Lower interest rates make a currency less attractive and will stimulate further inflation.

The question then becomes: how long will the depreciation pressures last?

Will it be a short, sharp shock or something more lasting? Generally the bigger a sudden stop in capital flows, the faster you see a reversal.

A big fall in one day generally isn’t a major concern, particularly if it’s temporary. What matters is if the run rate keeps going.

What happens next?

In this case, Turkey’s balance of payments fundamentals are good (it doesn’t owe a lot to other countries relative to its income) and it has high inflation.

At some point higher interest rates should be there to slow the excess credit creation that’s stimulating inflation. This will attract capital inflows from abroad.

However, doing the opposite of this is what contributed to currency depreciation and more inflation.

And an increase in inflation can lead to further currency depreciation as people want to move money out of a currency losing value. In other words, the interest rate being paid on the currency doesn’t at least pay for the rate of the depreciation pressure.

The only way to get out of this is higher interest rates than before and a longer-term view that inflation will fall sufficiently.

If Turkey’s policymakers keep doing the opposite of what’s appropriate the inflation and currency depreciation can get worse. If they eventually come around to not making further policy mistakes the currency should improve.

Will the Lira rebound from its currency crisis?

It should, but there’s a chance this could get worse if policy isn’t run well (e.g., further rate cuts, nothing done about inflation).

Currency crises like these can get worse and last longer if policymakers aren’t willing to admit mistakes and make changes.

At some point, Turkey will need to raise interest rates dramatically in order to slow credit creation and stop depreciation pressures that stem from the high inflation it causes – not continue with its current policy mix for too long without facing reality.

Traders are still watching for clarity on this issue.

Theoretically, the currency has to look attractive even though the tail risk (of further downside) is quite high if policymakers keep pushing in the other direction of what their economic fundamentals dictate.

In a worst-case scenario, inflation can runaway higher and the currency can essentially be ruined.

Can a weaker Lira cause contagion in EM FX?

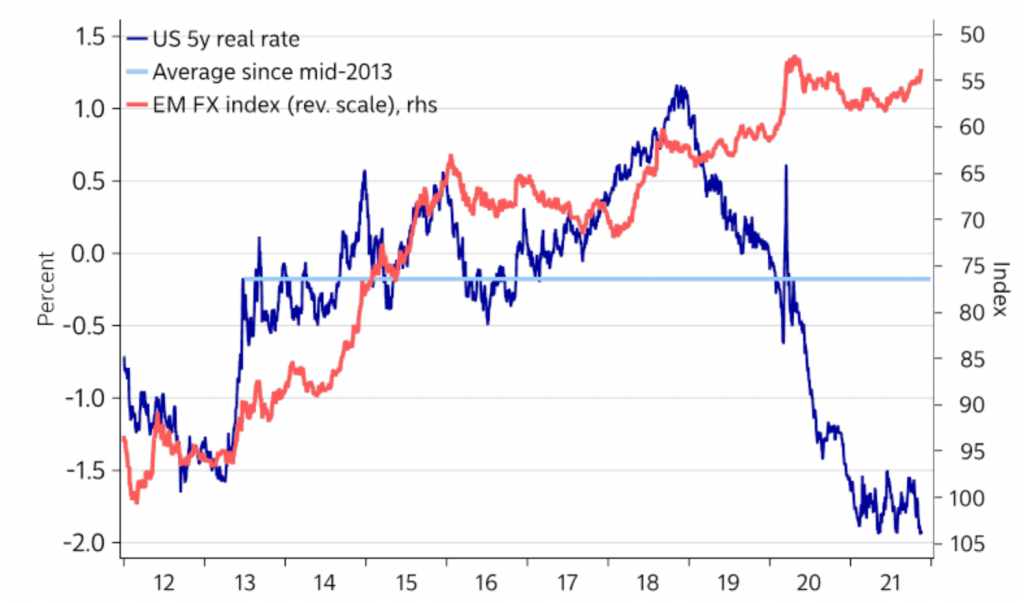

When US real rates start to climb, the USD should improve versus riskier EM currencies.

The fall in the Lira also showcased how EM contagion works. Following a path of rate cuts when inflation spikes blew the Lira to shreds, which also spilled into other risky EM currencies such as the Mexican peso (MXN) and South African rand (ZAR).

EM FX inversely follows US real rates. Emerging market currencies have stayed weak even despite US real rates going lower. That’s likely to get even worse when the Fed is forced to rein in inflation by hiking rates, which will cause US real rates to go higher.

Emerging market currencies are already weak – what will happen when US real rates climb?

(Source: Nordea, Macrobond)

Conclusion

Turkey faced both high inflation and favorable balance of payments fundamentals.

High inflation on its own favors rate hikes to slow credit creation.

Moreover, sound balance of payments fundamentals also supports rate hikes because they don’t need lower rates to stimulate exports and lower imports to close the trade imbalance.

What caused the recent collapse in Turkish lira?

After Turkey’s currency crisis and balance of payments crisis in August 2018, things had been going reasonably well for a while.

The country was running a large current account surplus, inflation was high (but manageable by raising rates), fiscal policy was under control, and so on.

Therefore, there wasn’t any real cause for alarm that could have triggered the big crash in Lira. Their balance of payments fundamentals are as good as they’ve been in a long time.

The August 2018 situation was a product of geopolitics. But November 2021 was a product of interest rate mismanagement.

It’s rare that central banks globally blunder this badly. Their mix of economic fundamentals favored higher interest rates, not lower.

There are cases where there are distinct trade-offs – such as high inflation on one hand (on its own favoring rate hikes) and a balance of payments deficit on the other hand (favoring rate cuts).

If they go in one direction or the other in these cases you can at least understand the thinking.

Turkey’s decision continues to show their central bank is not independent from political interference. The Lira fell sharply before the decision, expecting a follow-through on a policy error (and received it).

Traditionally, monetary policy has a bigger lever over the economy than what fiscal policymakers can traditionally do (because it’s hard for fiscal policymakers to act unilaterally and the central bank controls money creation and the incentives government credit formation).

The currency depreciated because the central bank let interest rates fall to try and stimulate growth.

However, now it needs rate hikes to slow credit creation and inflation (and make up for policy errors).