Direct Listings vs. IPOs: Knowing the Difference

More tech startups are opting for direct listings instead of initial public offerings as the preferred way of going public.

In this article, we’ll cover what direct listings are, how they work and why they’re popular among high growth companies, the pros and cons relative to the traditional IPO route, sustainability of this shift, and whether they could become the dominant model for going public for private companies.

Direct listing vs. IPOs

More tech, fintech, and other types of companies are focused on direct listings – also called direct public offerings (or DPOs) – as an alternative to the standard IPO process of going public.

It’s important to note that both direct listings and IPOs accomplish the same thing: a privately held company becomes publicly traded on a stock exchange.

This helps the ownership of the company’s equity go from a smaller number of private investors to a broader base of both institutional and retail investors. It also conveys certain other advantages, such as the greater brand awareness that comes from having a company’s stock trade publicly.

The main difference is that in a direct listing, no new capital is actually raised.

Usually when a company goes public, it does so to access capital from a new type of investor base beyond the standard private investment vehicles (e.g., venture capital, private equity).

The private and public equity in the company are listed on the exchange and can be traded, sometimes with restrictions – e.g., investor lockout periods of a certain timeframe (six months is common) to ensure a successful IPO (i.e., so private shareholders of the company’s equity don’t dump it all at once).

In a direct listing, investment bankers serve as financial advisors to the company in the process of going public.

For an IPO, the company hires investment bankers to underwrite the sale of shares that will raise capital for the company and/or its private shareholders.

Why do a direct listing?

There are a few main reasons why companies would consider going public through a direct listing.

i) Provide liquidity to shareholders

With a direct listing, a company’s entire shareholder base gets access to liquidity. This contrasts with the standard 180-day lockup period for private investors undergoing IPOs.

ii) Avoid dilution

A direct listing avoids the issuance of new shares. This helps avoid dilution of ownership in the company of existing shareholders.

iii) To provide greater access to a company’s shares

Direct listings help increase liquidity in a company’s equity. An investor can buy as many shares as they’d like.

iv) To increase price transparency through an auction-style price discovery process

During an IPO, a fixed number of new shares are priced within a certain range for the IPO.

A direct listing doesn’t involve this process. Instead, shares are listed directly and new investors participate in an auction-style price discovery process without artificial constraints from a reduced float.

Why are companies choosing direct listings?

There are several structural trends supporting direct listings over IPOs.

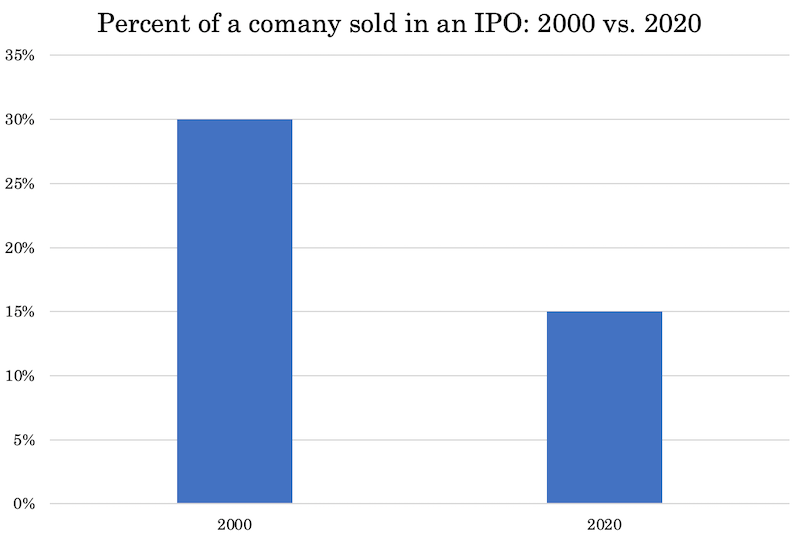

The biggest difference is that less of a company is currently being sold in an IPO than before.

In the 2000s, almost 30 percent of a company was sold during an IPO. Now in the 2020s, it’s only about 15 percent.

(Source: Dealogic, graph by daytrading.com)

The amount being sold is even less for more asset-lite companies like software who don’t necessarily need to raise as much capital.

There are a few main reasons for this:

i) Changing mix of business models

Software companies’ popular use of the subscription model has turned what would otherwise be capital expenditures into operating costs.

Tech companies don’t need as much infrastructure as they previously did with the growing popularity of cloud computing technology.

ii) Companies are going public later

In 2000, as a median figure, companies were five years old from inception to IPO. Today, it’s ten years old.

iii) The average IPO share price pop has gotten larger over the years

In 2000, the average IPO would receive a price boost of 20 percent on the first day. In 2019-20, this grew to nearly 40 percent.

For the high-growth group of technology companies going public in the 2019-20 period, the first-day pop is about 50 percent.

Issuers that received a large first-day boost may view the sharp rise as a missed opportunity to raise more capital and/or price the IPO shares higher than they were.

iv) Private markets provide more ample liquidity than they did before

Before, investment managers tended to specialize in stocks, bonds, private equity, venture capital, real estate, etc., and didn’t venture much outside of that.

Now, there are more crossover investors. Many want exposure to different asset classes to help build better portfolios.

This means more equity managers now invest in things like fixed income, private equity, and so on.

Moreover, constrained by a low return environment, this is drawing more public market investors into private investments.

The rise of growth equity firms is now more popular. Many private equity and venture capital investors also crossover into public market investments.

Direct listings help bring more liquidity back

Direct listing help bring liquidity back to the process of going public.

Four direct listings in 2020 had much higher free floats in comparison to IPOs that were constrained by traditional 180-day lockups.

This enabled public market investors to build positions more quickly, as opposed to lockups preventing liquidity from coming into the market until they expire.

Any company willing to go the direct listing route should be comfortable giving control on pricing and liquidity to the market. The lack of a lockup period takes away the share supply constraints that help make an IPO successful.

Where direct listings go from here

Direct listings are still relatively rare in comparison to IPOs.

All are naturally different. Each has a different financial profile, market cap, existing shareholder base, and story to tell investors.

More will follow and the direct listing process will evolve as time goes on. All types of companies will view their alternatives when it comes to capital raising and generating markets for their shares, whether that’s a direct listing, traditional IPO, or remaining private.

Companies could raise capital privately before a direct listing. This has included companies like Spotify, Asana, and Slack.

Each underwent a private round of capital raising less than a year before a direct listing. Not having a need for capital enabled them to be flexible in choosing their options between a direct listing or IPO when going public.

If more companies go this route, we could see investors who typically build portfolios of public companies become more active in establishing positions in private companies ahead of potential direct listings.

Public market investors have noticed that liquidity from direct listings is greater than a standard IPO and may be more patient once public to develop positions.

Palantir chose a direct listing but chose to lock up three quarters of its shares. This allowed for more liquidity than a traditional IPO to increase free float in the early days of trading.

But constraining the supply of shares still nonetheless gave greater control of liquidity than a regular direct listing where all is normally provided at once.

Direct listing may still be the best way to bring liquidity back into the process of going public with or without a partial lockup.