Which Currencies Do Best During a Trade Conflict?

Let’s start with a basic trading principle: When one country slaps tariffs on another country’s tariffs that is bullish for the tariff-implementing country and bearish for the country on the receiving end of them. It is an external shock that reduces national income for the recipient. The ongoing trade conflict between the US and China bears this out with the US dollar’s run against the yuan.

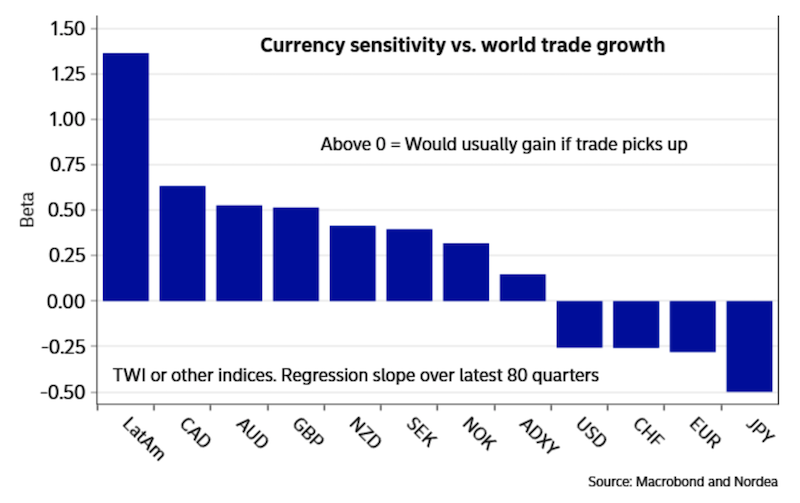

During the ongoing trade conflict between the US and China, Latin American currencies have seen the highest sensitivity (“beta”) to any ‘trade war’ related news. Among G-10 currencies, the Canadian dollar (CAD) shows the highest beta to world trade, with the Australian dollar (AUD) not far behind.

Part of the reason why is that Canada and Australia are commodity dependent economies. They benefit by selling their natural resources to other economies in need of them. The demand for these goes in step with the health of the global economy. Trade tensions between the world’s two largest economies creates uncertainty in business investment and supply chains going forward, contributing to lower forward expectations of global growth.

On the other hand, creditor countries that don’t have dollar-debt related issues – namely, they won’t be impacted much by a stronger US dollar – tend to benefit most. They act as safe havens on any adverse ‘trade war’ news. This includes the Swiss franc (CHF) and Japanese yen (JPY). Their overall lack of foreign debt obligations gives them strong control over managing these liabilities. Countries can control the interest rates and control the maturities when their liabilities are denominated in their own currency.

The CHF and JPY are also funding currencies in carry trades. When there is negative trade news, there is “risk off” sentiment which causes a deleveraging in risk asset trades, lowering the degree of speculative borrowing in these currencies.

If you are part of the camp that believes the trade conflict will not get better and probably get worse, you might expect currencies with a high beta to world trade to struggle for the remainder of the year. (US-China is a longstanding geopolitical conflict that’s following the standard template of what happens when an ascendant power challenges an incumbent power. This article goes into it this perspective further.)

This means currencies like the CAD, AUD, NZD, and GBP are at a disadvantage. Currencies like the USD, EUR, CHF, and JPY are likely to perform well by comparison, taking into account the trade factor alone.

Idiosyncratic risks are also in play.

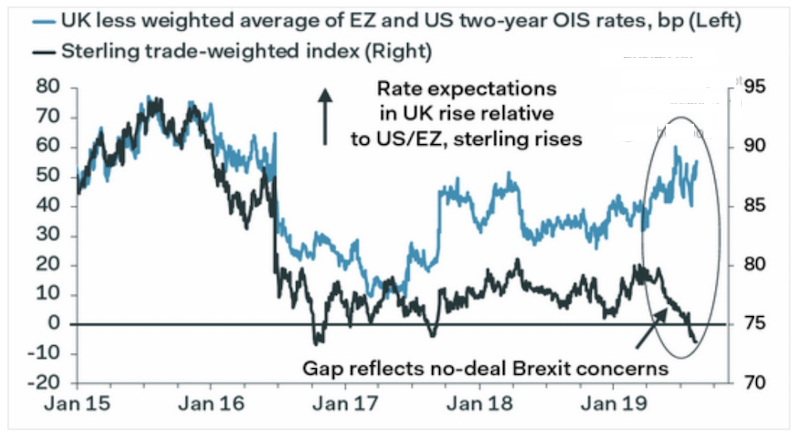

The GBP, at the time of publishing, is 1.21 to the USD and is a very crowded short trade. But it’s widely believed that the Bank of England will eventually get rid of their language about “gradual rate hikes”, which aren’t very likely to happen. The GBP is the cheapest to the USD since 1992, and many believe that weakness is merited for the time being mainly due to Brexit-related weakness.

Based on interest rate differentials – or the valuation of the pound relative to the interest income that can be achieved investing in a different currency – the GBP looks undervalued.

The trade conflict and the decline in yields

As the US and China’s trade conflict has increasingly been priced in as a long-simmering geopolitical tension (rather than the idea it can be assuaged through some “trade deal”), this has increased the demand for safe haven asset like US Treasuries, gold, and German bunds.

Compared to Japanese government bonds, US Treasuries trade a 0.60% premium on a currency-hedged basis.

The term premium on the 10-yr is about minus-133 basis points (an all-time low).

Conceptually, the term premium is if you take short-term Treasury bills, rolled them continually, and calculated what the equivalent yield would be on a longer-duration bond. When you compare that to the actual X-year yield and take the difference, you will have derived the yield premium. The “roll T-bills” yield would be 2.91% out to 10 years and 2.67% out 5 years. In other words, the extra compensation for taking duration risk by holding a longer-dated bond is the most negative it’s ever been in the US across a range of maturities.

This is commonly calculated using the ACM model, which is the most common (five-factor, no-arbitrage model).

The term premium is compressed heavily because people view longer-duration US Treasuries, which have structurally higher volatility relative to lower-duration bonds, as a positive carry hedge on equities. Many traders prefer going long Treasuries as opposed to long puts, bear spreads, and other hedging structures that cost them money.

With the addition of the trade conflict weighing on business sentiment, traders are more willing to pay a large premium to lock in yields on liquid, safe bonds. Even with many German and Swiss bonds yielding at negative-50 basis points (traders paying the government to take their money) it is hard to determine what the notional “equilibrium value” is with the regular flux in the tariff situation.

Moreover, mortgage portfolio hedging, pension fund asset/liability management, and CTA fund flows have helped drive rates lower in a self-reinforcing way. (Read more: Does Quant Trading Pose an Existential Threat to Day Traders?)

Given post-crisis legislation has limited the impact of commercial bank prop trading groups, who would normally be the ones, with plenty of liquidity backing them, to take a shot on catching “falling knives” in the market.

When interest rate curves invert, longer-dated bond yields will also bleed into expectations for the front end of the curve. With curves normally positively sloped, traders expect the inversion to eventually be resolved, usually through rate cuts at the short end, which central banks control.

In the US, the rates market has another four cuts priced into the front end of the curve over the next year (which is then extrapolated forward) despite the Fed’s suggestion that July’s rate cut was a “mid cycle adjustment”.

Escalation of the trade conflict and weak earnings mean more “risk off” sentiment

China manages its currency against what’s called the CFETS band, which is a basket of several different currencies, with more weight on the top reserve currencies.

It is broadly unknown the extent to which China’s policymakers pay attention to the US dollar when setting their valuation preferences for their currency. With the US dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency, it could be very reasonably assumed that China pays attention to the yuan’s value against the dollar. But it’s not explicitly known how much the USD/CNY exchange rate itself directly plays into its reaction function.

The 7.00 level in the USD/CNY currency pair was a psychological level. The break after the Trump administration’s rollout of 10% tariffs on an additional $300 billion worth of goods is a negative shock against China’s currency. As published in a different article, to offset the economic effects of these tariffs entirely, China would need to weaken its currency into the ~7.30 area, using the following math:

– 10% tariffs on $300 billion worth of goods is $30 billion (multiplying the two together) in terms of the change in national accounting

– The US imports approximately $500 billion from China each year

– Dividing the two quantities, $500 billion / $30 billion, that comes to a currency adjustment of about 6%

From the 6.88 exchange rate mark at which the “10 percent on $300 billion” was announced, this approximates 7.30 in terms of the new equilibrium exchange rate (6.88 multiplied by 1.06). To prevent a depreciation, China would need to use some of its reserves (a process that entails using other foreign currencies to buy its own currency).

Why does China want a stronger currency in effect? Because it’s transitioning from an export economic model to a consumption based economic model as the country becomes wealthier. This means consumers’ money can go further, primarily by making imports cheaper.

The idea that China wants a weaker currency broadly hasn’t been true for a decade now, when it was still focused on its export economic model as one of the world’s cheapest manufacturing hubs. Today it will only weaken its currency in circumstances where there is a catalyst driving it higher in order to stabilize its value. A stable currency gives the yuan (also commonly known as the renminbi, CNY, or RMB) greater credibility as a reserve currency.

To establish a reserve currency, it must be a viable enough means of exchange and store-hold of value such that it is held by other central banks, reserve managers, and large institutional investors. These represent the main entities that decide which currencies are important in the global economy and their relative standing among each other.

The country with the world’s top reserve currency also derives a positive income effect from that. The US is in a privileged position by having the world’s top reserve currency, and currently enjoys this advantage. The GDPs per capita for the UK, Japan, Germany – former global superpowers or countries that tried to become superpowers – have settled at about 20%-30% lower than the US’s and reserve currency status is a big part of this gap. (Japan’s was only about 10% lower at the time its speculative bubble collapsed in 1989.)

7.00-7.30 in the USD/CNY exchange rate is considered a “negative risk sentiment” zone. A break above 7.30 would represent a new escalation in the US-China conflict and would very likely go hand in hand with a further rise in Treasury yields and gold.

At the same time, President Trump very likely understands that upping the ante on the tariffs is a way to force lower rates out of the Fed. Lower interest rates help support growth and will help in his upcoming campaign for re-election. The US economy is likely to see several rates cuts over the next year going into the 2020 election.