Hiring Traders to Work for You: What You Need to Know

If you have a proprietary trading operation, multi-strategy hedge fund, family office, or other business designed to make money trading the financial markets, at some point you will probably want to hire traders to work for you (beyond the execution kind). It’s a way to scale and diversify your trading business.

However, for anyone who’s been involved in trading for any amount of time, you know that it’s among the hardest things to do. Markets provide constant feedback about the quality of your decisions and those with excellent track records over a sustained period are uncommon.

Below are some tips on how to improve your odds of successfully identifying trading talent.

Key Takeaways – Hiring Traders to Work for You

- Build scalable trading systems and proven strategies before hiring. Never hire to “fix” what isn’t yet working.

- Develop product or tech leverage first.

- Your core trading engine must generate consistent profits with minimal marginal cost.

- Use media leverage next.

- Publish insights, build visibility, and prove market demand before spending on ads or staff.

- Add people leverage third.

- Hire traders, analysts, or assistants only after your capacity is maxed and your edge is validated.

- Use financial leverage last.

- Outside capital should only amplify an already profitable, stable system.

- Prioritize evidence-based, logical thinkers with discipline and risk awareness.

- Evaluate traders over long, statistically meaningful periods. Short-term results are misleading.

- Align incentives and risk limits to prevent moral hazard or reckless behavior.

The Basics

Most trading operations that succeed in hiring and managing talent generally follow a progression of leverage.

The key is to maximize non-human leverage first, then use people to amplify systems that already work.

Hiring prematurely drains profits, complicates management, and introduces unnecessary risk before the firm’s foundation is stable.

1. Master Product/Tech Leverage First

Before bringing in traders or any help, it’s important that the core trading product or technology is sound.

For a hedge fund, that might mean refining models, execution algorithms, and/or research framework. The very foundation of it all.

For a prop trading operation, it could mean developing repeatable playbooks for strategies with clear edge and high return per unit of risk.

Action

Build a self-contained product or trading system that generates sustainable profits with low marginal cost.

Whether your “product” is a trading algorithm, research platform, product/service, or execution system, make sure it scales efficiently — meaning additional capital or trades don’t significantly increase overhead.

Once this base engine is reliable, you have something others can plug into and expand upon.

2. Master Media Leverage Second

Once the internal engine works, create media systems that attract attention, opportunity, and deal flow.

This could mean publishing whitepapers, running a YouTube channel, posting on social media, having a blog/website, or writing about your process in a way that demonstrates expertise.

Organic visibility becomes a major form of leverage.

Action

Use organic content to test demand and validate interest before spending money on marketing or recruitment.

In trading, this might look like sharing anonymized performance distributions, describing your research philosophy, and/or writing analytical content that separates yourself from others.

The value of an online presence depends on your business and personal preferences, but it builds trust.

This can be very helpful if you later recruit external talent or investors.

3. Acquire People Leverage Third

Only after your product and marketing engines are functioning should you start acquiring people leverage.

This is where you bring in traders, analysts, or developers to scale proven systems, not to fix unproven ones or try to experiment with the business.

Hiring prematurely multiplies chaos if the foundation isn’t in place.

Action

Hire traders or researchers when the founder’s/owner’s capacity is maxed out and the system’s economics are proven.

That means you can already extract predictable returns from your model or process, and additional manpower can genuinely scale profit and what some call a “cheat code” when it’s done well.

Use clear performance frameworks and risk limits, so each hire plugs into an existing machine rather than improvising their own.

People leverage can also come through virtual assistants or support staff for tasks like data cleaning, risk reporting, and compliance tracking.

Reserve your highest-caliber human capital for discretionary or high-value decision-making roles, not administrative clutter.

4. Acquire Financial Leverage Last

Once the system is profitable, stable, and predictable, only then should you add financial leverage through outside capital.

Financial leverage amplifies both skill and fragility.

If you add it before your organization and workers/traders have demonstrated consistent performance, it’s risky.

Action

Bring in capital partners or investors after all prior layers (product, media, people) are validated.

A strong, internally funded track record makes you far more credible to allocators.

At that point, outside money scales what’s already working rather than gambling on potential.

If you’re running a prop operation, you can also use profits to seed internal traders, giving them capital allocations proportional to demonstrated skill and adherence to firm risk protocols.

Why This Order Matters

Each form of leverage builds on the next.

Product leverage gives you something worth scaling.

Media leverage makes it visible and desirable.

People leverage multiplies output without breaking the system.

Financial leverage finally accelerates growth once stability is proven.

Hiring traders is tempting (it feels like an immediate path to diversification) but without proven systems, it layers human noise on top of unknowns.

The firms that endure treat traders as extensions of already-profitable processes, not as experiments to discover them.

Now, in terms of traders themselves…

Personality Tests

(1) Strive to incorporate psychometric and cognitive testing to assess candidates’ raw abilities.

There are many factors that go into what makes a sustainably successful trader. But more or less, it’s about finding individuals who can identify high reward-to-risk setups and positive expected value opportunities and having the courage to make them (or designing algorithms that trigger these decisions).

There is no set “type” or personality.

There are good extraverted traders and good introverted traders.

Some are very social by nature and some are very mathematical and analytical in nature.

Some are very creative and good at idea generation and some are not creative and simply piggyback on others’ trades.

Some are very “big picture” and some are more detail oriented.

All are in some form highly disciplined and are very competent at managing risk. A lot of the job is not so much doing anything “brilliant” but rather not doing anything stupid.

The well-known trader Bernard Baruch is often quoted with the following characterization:

“If you are ready to give up everything else — to study the whole history and background of the market and all the principal companies whose stocks are on the board as carefully as a medical student studies anatomy—if you can do all that and, in addition, you have the cool nerves of a great gambler, the sixth sense of a kind of clairvoyant and the courage of a lion, you have a ghost of a chance.”

Through experience, I have found that the best traders are always evidence based in nature over emotion based. In other words, there’s a strong preference for “thinking” (T) types over “feeling” (F) types, if we go by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator criteria (MBTI). (Specifics on the test can be found here.)

Most people tend to react more emotionally than logically. In trading, this produces outcomes like selling an asset as it gets cheaper. It takes the pain of losing money away, though it typically means the asset is getting cheaper and therefore a better deal. Or having a bias to hold onto something as it goes up based on the ostensible market feedback that it’s a good trade. (In reality, the risk/reward of the trade is probably becoming less favorable.)

Everybody has certain biases and opinions in their head on a range of subjects that can impact their trading behavior. Unfortunately, most of them are useless, or even worse – e.g., by feeding into a harmful mindset that becomes self-fulfilling. Less important is what one’s opinions are, but rather how they came up with them.

In trading, you have to figure out what’s true (or what’s most likely to be true) and what to do about it. You can’t confuse what you wish were true with what is actually true. You need to be evidence based. The range of unknowns is going to be higher than the range of knowns. Therefore, being aware of what you don’t know and knowing when not to have an opinion is more important than whatever it is that you do know.

Markets are very competitive and there are very few no-brainers that you’re going to be able to take advantage of. Every time you make a trade there is somebody else on the other side of it and it would be naïve to assume that you definitively have more information than they do.

Some ways of thinking serve well in some capacities and poorly in others. For instance, buying Tesla stock because one believes that electric cars “should” be the future without accurately ascertaining relevant macroeconomic and industry trends and Tesla’s individual operational, financial, and strategic circumstances makes for a very poor reason to trade it.

For this reason, for anybody who relies on the MBTI or similar type of personality assessment to assess traders’ competencies, you are very likely to have a strong preference for “T types” over “F types”.

Numeracy and Logic Tests

All traders need to be mathematically inclined in some form. You’re dealing with prices, metrics, risk and reward calculations, and various other matters involving numbers.

Therefore, many prop trading operations want to ensure that their candidates have adequate mathematical reasoning skills. For some, this might mean mental math tests. For others, it might mean reasoning exams (e.g., the Wonderlic test) and/or assessments that require a time element to evaluate mental processing speed.

If anything, it can be a “weed out” exam. If you’re posting available trading positions on job boards, it’s not uncommon to get thousands of applicants for a single position. It isn’t feasible to read through each application or resume, so a test or series of tests that can determine a basic set of proficiencies can whittle down the stack considerably.

Culture

(2) Think about the culture of your organization.

Most companies will tend to overvalue skills and abilities and undervalue a candidate’s character and values. This is natural when the key focus is on simply getting the job completed.

But values, or the beliefs that influence and activate behaviors and determine people’s compatibilities with each other, are what bind an organization together. All organizations need to operate by some set of common values in order to perform well together.

Relationships bound together by common values will help bring companies through the natural ebb and flow associated with business.

A company’s culture and its people are self-reinforcing. A company’s culture will tend to attract certain types of individuals. The people in the organization will in turn either reinforce the culture or transform it in a way based on collective values and what the people in it are fundamentally like.

Most organizations recruit ineffectively. People within the organization (who may or may not be best equipped to evaluate resumes) will use their own loose criteria of who might be a fit, which then leads to invites for interviews with groups of people (who also may or may not be equipped to get at the information they need to) who ask questions largely unsystematically and then hire based on whoever they liked the best. What questions do you need to ask, and how do candidates’ different responses help differentiate them in the ways that you’d like to differentiate them?

Training

(3) Training or education might be involved

Not all organizations can afford the luxury to train entry-level talent. If you need a trader to hit the ground running, you will probably not be able to train them in the same way a bulge bracket investment bank might.

Then again, even after testing for abilities at the outset of the process, people with the abilities don’t necessarily have the skills needed to succeed. Trading experience could be a requirement, but you may not be able to confirm such experience (e.g., through a third party auditor) or know whether it was useful.

Length of Track Record

(4) Make sure you’re evaluating over a statistically meaningful period

Weeks, months, or even 1-2 years may not be enough to reach statistically meaningful conclusions about whether a prospect has trading talent. This will be developed down below in more detail.

Treat everyone fairly, not equally

(5) No two traders have the same exact amount of talent. Treat each accordingly.

Just as you might commit more money to a quality trading idea and less money to a lower quality idea, it makes sense to give more capital to those who you have more confidence in and less to those who you have less confidence in, rather than treating everyone equally.

Watch incentives and watch your risk

(6) Don’t let free-riding and unaligned incentives be an issue.

In some organizations, when people gain access or control over resources that aren’t their own, they may be inclined to use them in an aggressive, reckless, or unprincipled way. That could include actions that earn them a large bonus if they’re right and, if they’re wrong and blow it, the losses get socialized among the owners of the firm. But you can’t let the probability of the unacceptable happen (a rogue trader blowing up) because they don’t have the appropriate guardrails in place due to agency issues.

This is why some firms institute capital contribution requirements to a some extent. That helps to equate the firm’s success (or the quality of a trader’s decisions) with their own success.

Evaluating Performance

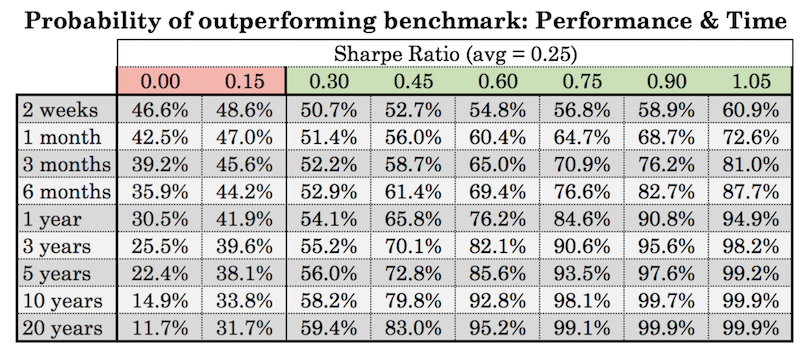

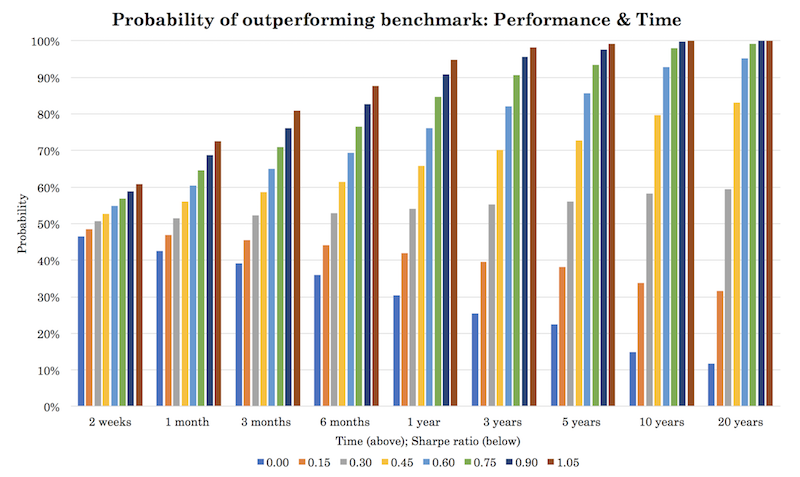

Below you can find a table and graph of the probability of a trader outperforming a benchmark based on their talent level (represented by a Sharpe ratio). It can help act as a conceptual guide to help think about how you can know whether a trader adds value.

This is a function of two things:

(1) their talent level, which could be theoretically embodied by one or more risk-adjusted return metrics, such as their Sharpe ratio (the industry standard) and,

(2) the amount of time elapsed

Financial assets are expected to have Sharpe ratios of 0.2-0.3 over the long-run.

How do we know this? Individual asset classes, often called “betas”, are expected to have ratios where excess returns relative to their excess risks (what the Sharpe ratio calculates) are around 0.2 to 0.3. This is because of two things:

a) there needs to be some type of expected return in order to compensate traders for taking on risk in excess of a “risk-free” asset (making the ratio positive), and

b) this ratio cannot be particularly high because all investment compete with each other and high excess returns relative to excess risks would attract in capital and increase their prices and lower their forward expected return.

I assume that the S&P 500 and other betas will have a long-run Sharpe of 0.25 (the threshold for a trader adding value).

0.3 is considered barely above average, and 1.05 is considered exceptional (more than doubling the risk-adjusted return of SPX or another benchmark), a level that very few perform at over the long-run.

Sharpes of 0.00 (basically investing in cash) and 0.15 (better than cash, but less than the expected Sharpe of equities and other betas) are value destructive over the long-run relative to investing passively. This is borne out in the numbers with their probability of outperforming the benchmark below a coin flip’s chance and falling steadily as time goes on.

Table

Graph

The main takeaway is that at very short timeframes, it’s very difficult to accurately assess the talent level of any given trader.

The exception obviously is the very worst performers. For example, if a trader operates at a Sharpe of minus-2.00, then you know with ~80% odds that they aren’t any good over a timeframe of two weeks.

A trader operating with a Sharpe of 0.00 will outperform the benchmark about 43% of the time over the course of a month. Somebody who has reasonable talent (Sharpe of 0.60), will only outperform the benchmark about 60% of the time over one month.

Trading talent naturally falls along a distribution, and most traders are going to be operating at Sharpes of 0.45 or less over the long-run. In other words, they won’t be beating the market by much and most won’t at all.

So, determining the talent level of a trader or manager requires an extraordinary level of patience, far more than most would imagine. Investing in a high-quality trader takes less patience, but these are rare, and on a shorter timeframe is likely to be a “false positive”.

Accordingly, this is why you might prefer to collect data using psychometric and cognitive exams. You are more likely to make higher probability bets about who’s likely to be good and who isn’t.

Some firms (typically upstart firms) have tried to get creative with the recruiting process by using contests and tournaments. The idea is that if they simply roll out their search to a wide audience through an intriguing or chic format, and observe who has the best results over a (necessarily) short timeframe, that this could provide a reasonable way of finding a good trader.

The problem is it’s almost impossible to get anything statistically meaningful out of performance on such a short timeframe.

Performance within the context of the market environment is also important. Traders are naturally biased toward their own domestic equities markets. So, if that’s had a good run over the tracked period and a trader is simply doing something very similar to an index, then that plays into the equation.

And the incentives that “maximum return” contests create are mostly bad, primarily in the form of excessive risk-taking. The easiest way to win a “trading contest” is to bet everything, or more than everything through leverage, on a very volatile security with an event coming up that is likely to materially move the stock (e.g., earnings) and rely on the binary outcome to produce the returns needed.

Of course, nobody would ever responsibly manage their own money this way.

The folly of evaluating over short timeframes

Let’s look at a hypothetical. Say a prospective trader has no track record, is entry-level, but shows promise and you need to find out his ability within a reasonable timeframe. This is similar to how a bank would treat a new trader coming into the firm.

Let’s say you see a trader performing at a Sharpe of 1.00 over two weeks on a trial period (his excess returns equal his excess risk), which is great.

What is the probability that you know you’re better off investing in this trader than SPY (a market-following exchange traded fund)?

Only about 60%.

If he repeats this performance (Sharpe of 1.00) over another two weeks, your probability of being right is now still only about 71%.

These odds are decent. But if this is also the stage where if this type of performance meant he’d be getting some amount of the firm’s capital, this also might change his behavior if he’s making no capital contribution of his own. If he makes a concentrated bet that works out, he could make decent money. If it doesn’t work out, then the losses are socialized among the owners of the firm.

Let’s say the trial period is elongated into a period of three months.

If he then performs at a 1.00 Sharpe level, your odds of being right about this trader increase to close to 80%.

You could also feel more confident if he was originally phased in by getting past an initial psychometric screen – i.e., you feel comfortable about his processing speed, numeracy, pattern recognition, etc. – because that would increase your odds of being right further.

If a trader is performing at a 0.40 Sharpe ratio over a three-month trial period, your probability is about 57%. If he was screened in with a valid cognitive assessment, then you could be more confident or start more cautiously relative to a higher performer (e.g., start him at a lower starting capital balance).

Conclusion

Conceptually, the methodology that you’d use to hire traders is really not much different than the way you’d go about determining which bets to take in the financial markets. You are using imperfect information to assess your odds of being right about the type of value you’re going to get.

You need to best know their values, abilities, and skills, preferably with a focus on that order.

What motivates them? What are they like – in other words, what is their personality, what are their ways of behaving and thinking, and what competencies have they developed?

For long-term partnerships, ensure not to overvalue skills relative to abilities and values. People in your organization should ideally be on the same mission together and feel a sense of community.

Track records matter. The past isn’t necessarily indicative of the past, but if you’re going to rely on another individual to generate you revenue, they should demonstrate a track record of success in the thing you are potentially relying on them for. If someone is expected to be able to do something, then there should be ample evidence that they’ve accomplished it in the past, preferably multiple times or over a sustained period to draw statistically meaningful conclusions.