Currency Intervention: Can Trump Weaken the Dollar?

Experienced currencies traders know that government sponsored currency intervention is part of the game and can come out of the blue even when you may not expect it. Forex as a whole is a difficult asset class to trade with any degree of precision because there are so many factors that ultimately influence its behavior. It’s like having a dozen different doctors operating on the same patient without a clear grasp of what each is doing at any given time.

This contrasts with trading something like short-term interest rates (e.g., of under a year) where the only thing that’ll make you right or wrong on your trades is what the central bank controlling said rate does.

Since the late 1990s, US currency policy has been predominantly hands off. By having the luxury of having the world’s primary reserve currency, the US has largely let market forces dictate the direction of the dollar.

By and large, markets are a better determinant of how one currency should be valued relative to another and how capital should be allocated. Central intervention takes time, effort, and may cause distortions rather than alleviate any problems. Only twice in the past two decades has the US Treasury intervened in the dollar market.

However, within the Trump administration, the idea of government intervention in the dollar market has been considered. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin stated publicly that he has not ruled out currency intervention as a policy tool. Some within the Trump administration have been less receptive of the idea of the US intervening, but with Trump’s and Mnuchin’s stance on the topic as the “number one” and “number two” authority figures when it comes to this matter, the idea of dollar intervention should stick in traders’ minds.

The US has $94 billion in its Exchange Stabilization Fund, but that’s quite small relative to the $4.4 trillion daily turnover of the USD (47x smaller, to be exact). And it’d be sterilized intervention given it would have no influence on the monetary base.

The dollar is overvalued in the long-run with twin deficits (i.e., current account deficit and fiscal deficit) and large non-debt liabilities in the form of, most notably, pension and healthcare obligations.

However, the re-buildup of the Treasury’s general cash account (GCA) will keep the dollar elevated for the remainder of 2019, as a way of diminishing USD excess liquidity. It’s the only major developed economy with interest rates notably above zero. And the USD is a safe haven when global growth expectations recalibrate downward and are less synchronized, which bids up its value in relative terms.

Many traders believed that 2019 would be a year in which the USD would decline. The idea was that the Fed opened the year walking back on their expectation that it could no longer hike interest rates, or at least not very much. Moreover, with the US yield curve priced between 2.5 to 3.5 percent at the time, and all other developed markets at 1 percent on down (and into the negative yield area), the idea was that the Fed could cut rates much more easily on a relative basis.

Even with that same idea in mind, there are already 4 to 5 Fed 25-bp rate cuts priced into the curve forward one year (as of early September 2019). These are already expected and therefore baked into the pricing of the dollar. Fed easing is also being offset by easing elsewhere.

Accordingly, USD rate differentials relative to other currencies are not moving much. A higher inflation-adjusted interest rate relative to another will tend to result in an appreciation of its currency (because it yields more).

Foreign Exchange Policy versus Economic Policy

There’s an inexact line between where foreign exchange policy and economic policy differentiate themselves.

Tax policy, fiscal spending, subsidies, and monetary policy (changing interest rates and the money supply) all impact exchange rates. When policymakers deem these measures to be insufficient, they may turn to capital controls to prevent wealth and currency from being moved offshore. Historically, this has also at times included a banishment of gold ownership.

Price and wage controls may also be enacted. (Typically, they fail to rectify any imbalances and achieve the intended result, often by causing distortions and inefficiencies.)

Capital controls are used with some frequency in emerging and frontier markets (e.g., Argentina), but most developed markets have left them out of the toolkit of viable policy options. The Trump administration, and Secretary Mnuchin in particular, are probably not considering capital controls but rather currency intervention.

Currency intervention entails the central government or central bank going into the market and buying or selling domestic currency. Currency interventions are assumed to work because the resources of government or government-like institutions (e.g., state-owned enterprises) have more resources than private sector participants in these markets. They can simply “print” their own currency and buy foreign currency with it.

However, currency interventions have had mixed results. Let’s briefly digress with the popular example of the British pound (GBP) in the early 1990s.

At this time, the British pound had broadly kept in step with the German mark. However, the Bank of England didn’t have the reserves available to keep the pound within the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), which acted as a unification precursor to the European Monetary Union. The rate was kept at 2.7 German marks per pound.

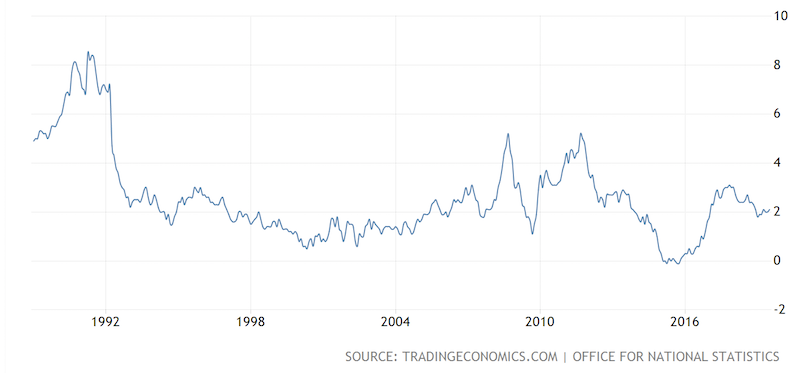

The UK needed higher interest rates given its inflation rate had gotten out of hand at approximately 8 percent. (Note the early 1990s portion of the graph below.)

To that point, because of the ostensible virtue of having greater monetary and economic cooperation between European countries, the UK had agreed to keep its interest rates artificially low. However, once price pressures and inefficiencies pick up to a high enough extent, it’s not a sustainable set of economic conditions.

The Bank of England had to buy its own currency with its foreign reserves to keep the pound pegged to the mark. Many market participants, most notably George Soros due to the size of his bet, believed (in reality, knew) that the BoE couldn’t sustainably do what it was doing to fight natural market forces. So, they decided to short the currency.

The BoE tried to counter by raising interest rates to attract inflows into the pound, but it had little effect in convincing the market of what was an eventual economic reality (that it would run out of reserves), and the British government relented and let the pound fall out of the ERM.

This is a prominent illustration that government intervention in currency markets is far from a bulletproof situation. This is particularly true in scenarios when their desires about the way they want things to be aren’t consistent with reality. Exchange rate regimes that aren’t consistent with economic fundamentals inevitably fail.

When currency intervention works and when it doesn’t

Government intervention can work in instances where there is coordination between countries and market participants. The 1985 Plaza Accord was successful in reversing the US dollar’s strength versus other developed markets. This was broadly a result of cooperation and synchronization among the G-5 nations at the time to achieve exchange rates that would help these countries collectively achieve their economic objectives.

The Louvre Accord, signed 17 months later, was agreed to as a consequence of the success the Plaza Accord achieved and to halt the resultant depreciation of the US dollar that had come out of that agreement.

However, when countries decide to act unilaterally, they typically fail to achieve their objectives. When the US attempted to intervene in the dollar market in the mid 1990s, it did not effectively stop the US dollar from falling against other developed market currencies.

The basic mechanics of the process of halting a depreciation is to sell foreign currency to buy your own. However, reserves are finite in quantity.

Moreover, traders know the approximate levels of reserves each country has. When they begin to run low, they will be inclined to expect that the government will be out of ammunition and have no other option but to depreciate. When the US tried intervening in the dollar market to stop the dollar’s depreciation, it did not run out of reserves, but it didn’t use an adequate quantity to impact the market to any appreciable extent.

During the Asian crisis of 1997, sharp moves in various currencies took place because of the issue of insufficient reserves. Currently, China is dealing with the same issue to a degree. When the US imposes tariffs, this is an external shock that reduces China’s national income relative to future expectations. Given China’s goal of having a stable currency and imposing a more consumption oriented economy (rather than an export based economy), it wants to avoid any material depreciation.

However, as China found out in 2015, a managed depreciation tends to burn through reserves. Obviously, the market wants to front-run the move. Chinese policymakers need to ideally signal to the market that it won’t let the yuan depreciate below a certain level.

Depreciating is easier than appreciating

Intervening to depreciate one’s currency is easier than intervening to appreciate.

This should make intuitive sense. If you want to increase the value of something, that takes care, attention, diligence, and strategic input over time.

If a country wants to depreciate its currency, one way is to convince the market that its country is an unattractive place to invest in relative terms. It doesn’t take much for a country’s leadership to convince the rest of the world that their country is not an ideal place to invest. They can simply “print” as much of their own currency as they need to and buy foreign currency.

Nonetheless, this is sometimes easier said than done.

Switzerland, as a twin surplus country (i.e., fiscal surplus and current account surplus), is viewed as an attractive place to invest in “risk off” periods because of its strong balance of payments situation. It’s had this issue ever since the EU started having economic difficulties, which led to domestic investors repatriating their capital into Swiss-based assets. This has led to levity in the CHF market.

Moreover, because of its already low rates, the Swiss franc is often used as a funding currency to purchase assets with higher yield (see: carry trade). When there is risk off sentiment in the market, those trades typically come unwound. This creates a short squeeze as the CHF funding is pulled back. In turn, this pushes the currency up.

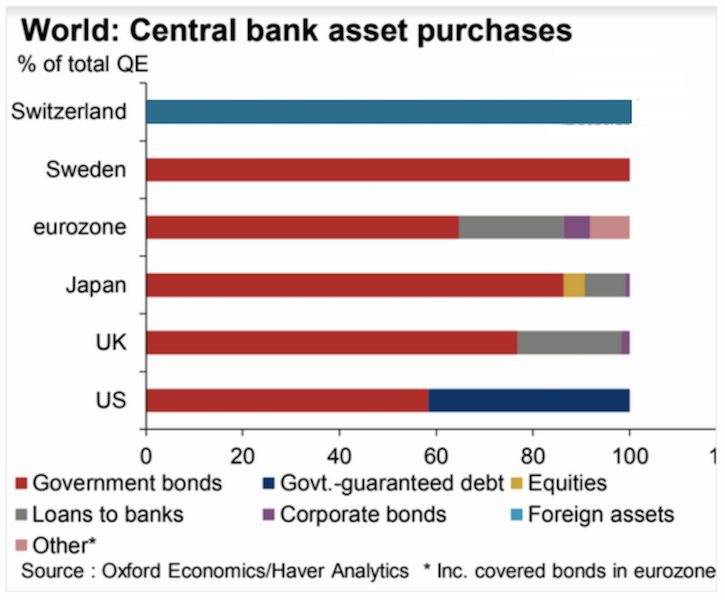

For now, the Swiss National Bank has reacted through low rates to stimulate capital outflows (exports) and has also done its quantitative easing (QE) program much differently from other countries. Instead of buying domestic assets like all other central banks with QE programs, the SNB has “printed” money to purchase outside assets, including US stocks. This is designed to push out liquidity, and raise the dollar relative to the CHF to boost the domestic economy.

When a government “prints” money and sells that currency, it acquires foreign currency, which it then manages on its balance sheet. A central bank can also use a tactic called “sterilization” to offset any increase in the money supply.

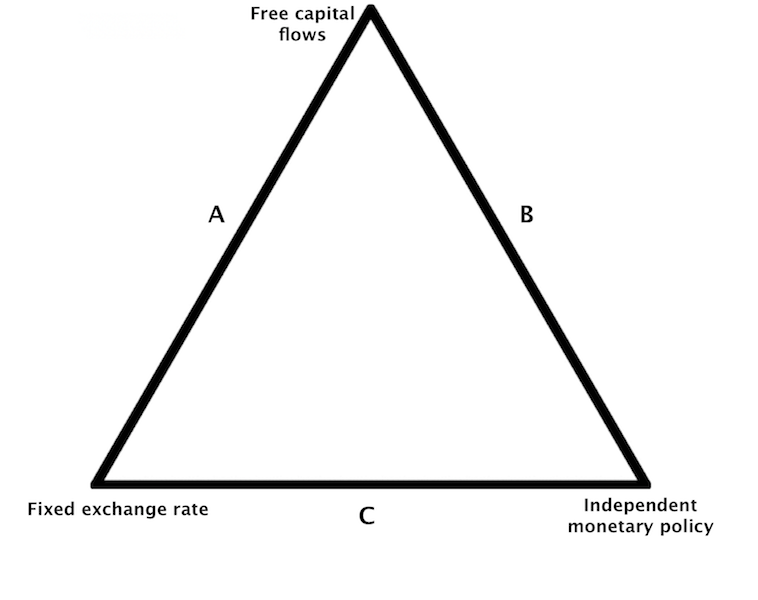

However, a country with an open capital account cannot directly control its capital flows. These flows influence the exchange rate. The exchange rate impacts nominal interest rates. The technical difficulties in simultaneously managing capital flows, the exchange rate, and the autonomy of monetary policy simultaneously is what macroeconomists call a “trilemma”.

The diagram below illustrates these sets of trade-offs. When a country decides on how to run its currency policy, it must effectively choose one side of the triangle, choosing to focus on two of the three at the exclusion of the third.

This is a topic in itself and will be expanded upon in a future post.

Is Trump right that the dollar needs to be weaker?

From the US point of view, it would indeed be of benefit, on a macro level, to have a dollar devaluation relative to current levels. That would help get US pricing in line with the rest of the world.

We’re in a disinflationary environment due to a confluence of factors, including high debt, sluggish productivity, declining growth (effect of the washout of the 2017 tax cut), and various technological innovations and labor arbitrage behaviors keeping price pressures under control.

So, US policymakers should be content to see the currency settle downward in terms of the equilibrium point.

However, I don’t believe we’ll get that in 2019 or the first part of 2020 due to various reasons – e.g., buildup in the Treasury’s general cash account, increased foreign repo pool demand with a flat / inverted curve (a supply-side effect on the USD through reduced bank reserves), foreign demand for safety and liquidity, and high relative real rates compared to other G-7 countries.

The US also has a lot of external debt denominated in dollars – roughly 45 percent of domestic GDP. To get relief on this front, the US would want to see the dollar depreciate. Other countries are getting their currencies down too, at least relative to gold.

Foreign exchange devaluations also help risk asset markets, holding all else equal. One of the best ways to keep a floor under stocks is to devalue the currency.

Conclusion

While the White House has, for now, ruled out currency intervention, it’s a potential tool when it comes to influencing the currency markets.

The Trump administration hasn’t been pleased with the Fed and its hesitance to cut rates as aggressively as it would prefer. If the Fed remains that way, the White House is more likely to consider currency intervention as a backdoor tactic to loosen monetary policy. (More on Trump’s thinking and motivation regarding interest rates can be found here.)

Given the role of the USD in not only currency markets but in all markets as the top global reserve currency, this storyline of US currency intervention is important to track going forward even if it seems off limits currently.