Negative Interest Rates: Can They Continue?

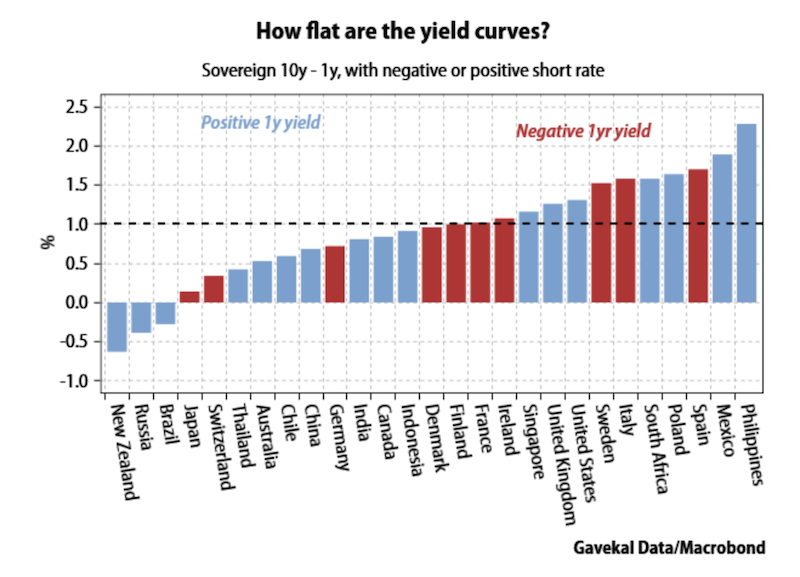

Negative interest rates are now a fixture in the financial world. Most developed market countries currently have negative interest rates of some form. Some remain “holdouts” – most notably the US to go along with the UK, Canada, and Australia / New Zealand, but Japan and most of developed Europe are below the zero level on most of their sovereign yield curves.

Negative interest rates are counterintuitive. Under these arrangements, this means a lender will pay a borrower when they extend credit. Typically, if you borrow money from someone, you have to pay them interest. In this case, the standard relationship is flipped on its head.

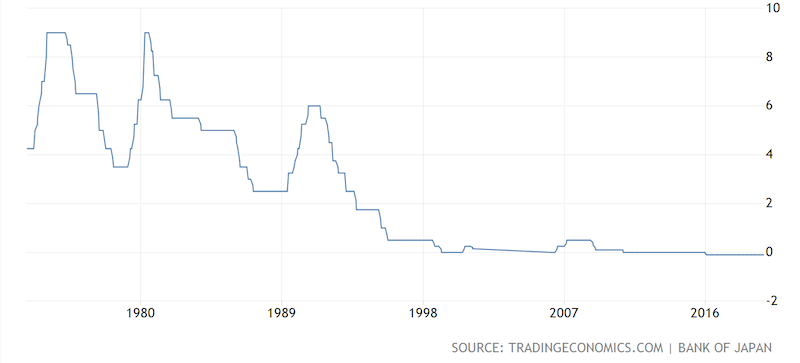

Japan introduced negative interest rates in 2016, going to minus-10 basis points, though has already been at zero or very close to zero for the past twenty years.

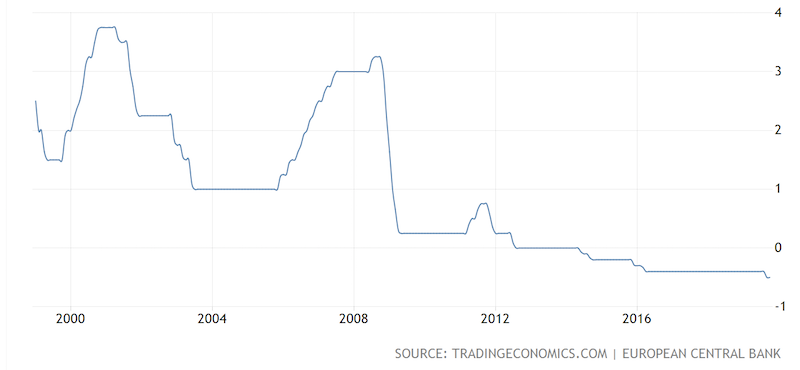

The European Central Bank reduced the rate on its credit facility to minus-10bps in 2014.

In other words, these central banks are paying those that borrow from them at these rates (i.e., large commercial banks).

To date, we don’t know how much more prevalent they’ll become, what the ramifications of them are, how long they’ll continue, or whether they’ll also become mainstream in the remaining developed markets with slightly positive rates.

How are interest rates determined?

First, we should explain what makes an interest rate sustainable.

An interest rate represents the price of credit. (An interest rate is not the price of money as commonly described. Credit – an asset for a lender and a liability (debt) to a borrower – is something that has to be paid back. Money, on the other hand, is what payments are settled with.)

What households, companies, and governments are willing to pay for credit has to be in line with the feasible ROI they can achieve on a project or initiative. At the macroeconomic level, if an economy is growing by 2 percent in real terms and has an inflation rate of 2 percent, it is growing at a nominal rate of 4 percent combining the two.

Nominal interest rates, or the cost of capital, for most players in this particular economy could not exceed 4 percent. Why? Because the debt would compound faster than the economy would grow. Whatever income is generated from the project would be swamped if they were paying more than that in interest expense. At some point, debt problems would emerge and the debt servicing requirements would need to be eased.

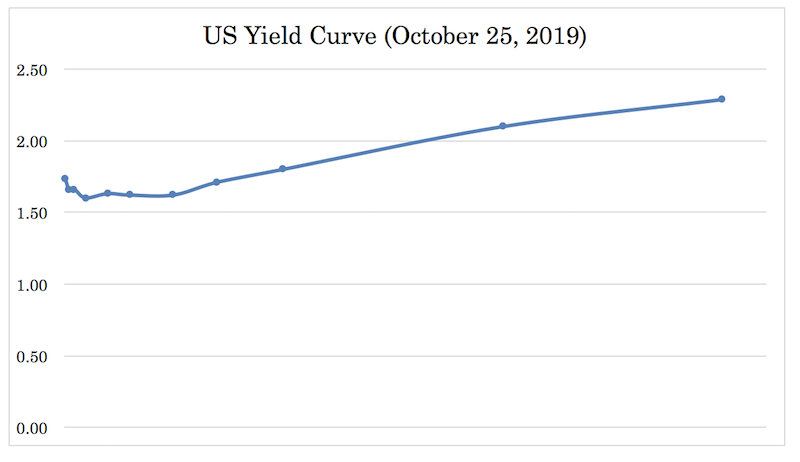

So, broadly speaking, the central bank should keep rates under 4 percent in this type of economy. Because rates at the short end of the curve are typically lower than those further out on the curve and the rate at which loans are extended in the capital markets – a function of greater duration risk and credit risk – short-term rates should be reasonably lower than nominal growth. For example, short-term rates might be 2 percent. Short-term rates also feed into the rest of the curve.

If debt growth is too high relative to income growth, the central bank might want to be tighter with its monetary policy, and looser if debt growth is too low relative to income growth. If the operating capacity of the economy is too high relative to its potential capacity, then it might want to also be tighter, and vice versa. Moreover, if there is excess speculative activity in the markets, then the central bank may also want to be tighter, and vice versa if investment activity is too low.

These all should in some form play into a central bank’s reaction function.

Negative rates suggest that nominal growth is so low that front end rates should be below zero to stimulate the economy.

Before the 2007-09 financial crisis, putting your money into developed market sovereign bonds was a straightforward way to make money. Developed Europe still gave you 3 percent or higher yields and US yields still gave you north of 5 percent.

Since then, due to lower growth, lower inflation, belief in the use of sovereign bonds as effective hedges on equity portfolios, the yield on these bonds has gone materially lower.

In the US, real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) yields are now below zero or right at zero. In much of Europe and Japan, the nominal yields are negative and real yields are even more negative. People are paying to store their money in a safe place.

Europe went to negative interest rates to help resolve debt issues that have popped up in “periphery” markets like Greece and Italy. Commodity prices were also very high in 2013-14, which fed into higher consumer and corporate costs for importers.

Typically, commercial banks earn interest on the excess reserves (a form of cash) they hold at the central bank. This is true with the US Federal Reserve and ECB. Negative interest rates earned on those reserves forces them to pay money to the central bank. This dis-incentivizes them from holding them. In theory, this should make them more inclined to lend, which should boost the economy. More credit availability typically leads to more investment and greater spending.

Negative interest rates feed into negative rate bonds

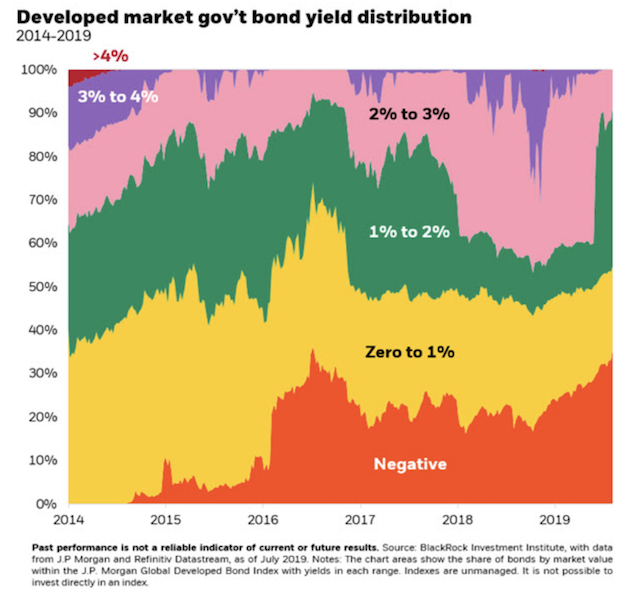

Today, we have roughly $17 trillion in negative yielding bonds. These are most sovereign bonds from developed Europe and Japan. Roughly 90 percent of developed market government bonds now yield less than 2 percent:

Some corporate bonds also yield negatively, including some “high yield” bonds that also trade at negative rates. About 25-30 percent of all investment grade debt in the world now trades at negative rates.

If we adjust for inflation, about $36 trillion worth of bonds yield negatively. Some $9 trillion worth of US government bonds yield less than the CPI inflation rate. So, even in the “positive yield” US, about 25 percent of the world’s negative rate debt exists in inflation-adjusted terms.

Here we can find the rates by different markets (China is still considered an emerging market):

Why would you buy something with a negative interest rate?

This was written about in a previous article at greater length. Basically, to rehash, when you buy something with a negative rate your total interest received will be negative. This means that if you buy a negative yielding bond and hold it until maturity, it’s a lock that you’ll lose money.

Why do people buy them?

– Some might expect deflation, meaning a bond could give them a positive real return in that case, or at least a less negative nominal return.

– Uncertainty regarding the future or a hedge against risk assets. Many investors like to put all their money into stocks. Stocks can lose 20 to 90 percent in a recession or in a bad debt crisis. In the US, stocks lost 89 percent peak to trough during the Great Depression and 51 percent peak to trough in the 2007 to 2009 period. The NASDAQ drew down 80 percent from March 2000 to October 2002 due to the combination of an overvaluation and US recession.

Viewed from that perspective, losing only 1 percent per year on the lowest yielding bonds doesn’t seem as bad against the prospect of losing much more.

– There is a lot of liquidity from central banks buying over $15 trillion worth of financial assets since the 2008 financial crisis. This all inevitably gets into asset prices. Negative interest rates are, in part, a manifestation of too much cash chasing too few assets.

– As a speculative instrument to bet against a further drop in interest rates. If rates are going to decline even more, holders of these bonds make money on a mark-to-market basis. The longer the duration of the bond, the more sensitive it is to interest rates.

– As an FX trade. Some may want to bet that the currency the bond is denominated in will appreciate by more per year than the associated interest rate.

– The rate on it can still be positive if hedged in a different currency. For example, for US traders buying European sovereign bonds or Japanese government bonds, when hedged back into USD they provide a positive nominal yield.

Based on the idea of interest rate parity, currencies that have lower interest rates are expected to trade at a higher exchange rate in the future. All currencies that have zero/negative interest rates – e.g., JPY, EUR, CHF – have upward-sloping futures curves against the USD.

The interest rate parity formula is represented as:

F = S * (1 + domestic interest rate) / (1 + foreign interest rate)

F = forward exchange rate

S = spot exchange rate

Let’s do an example between the US and Japan:

If the forward one-year interest rates are 1.6 percent (US) and minus-0.24 percent in Japan, we can put these into the formula, knowing the current spot exchange rate of 108.62.

F = 108.62 (1 + 0.016) / (1 + -0.0024)

F = 110.62

This means that for a US investor putting their money into a bond yielding minus-0.24 percent, when they hedge this back to USD they earn:

110.62 / 108.62 * (1 + -0.0024) = 1.60%

This assume frictional costs are negligible (e.g., commissions, slippage). In other words, the 1-year yield between Japan and the US should be more or less the same given this arbitrage process.

Interest rate equilibrium

As above-mentioned, from a macro perspective, interest rates need to be below nominal growth to keep the debt servicing sustainable. Debt servicing cannot exceed income growth for very long. Debt can rise faster than income so long as the debt serviceability remains low.

So, central banks need to keep debt growth in line with income growth. Credit is the main driver of spending power in an economy, so it’s very important. If credit growth is too low, the economy will underperform. If debt growth is too high, there will eventually be a serviceability issue and the economy will contract.

At a more microeconomic level, lenders will want a return that helps compensate for the time value of money. To different lenders this will be different amounts. The capital markets will largely dictate these rates.

If lenders want a 3 percent annualized real return and inflation is expected to run at 2 percent over the next ten years, then the nominal rate they would charge for a 10-year loan would be 5 percent. However, if the expectation is that inflation will be minus-3 percent (i.e., deflation), then that type of loan should yield zero percent, in theory.

Market competition is a big factor in determining what lenders can charge what. And because the commercial banking system is so intertwined with the central bank or central monetary authority in most countries, this institution has such large reach over what banks, non-banks, and other financial intermediaries can charge.

So, we know that negative rates are following the same type of dynamic as any form of interest rate. They are some combination of the following:

– Nominal growth expectations (real growth and inflation)

– Changes in real return expectations

– Market competition among lenders and other microeconomic supply and demand factors

– A result of central bank policies

More detailed reasoning for negative interest rates

At a broad level, the reasons just mentioned go a long way toward explaining changes in interest rates.

We could break it down in a bit more detailed way.

– Central banks can push interest rates lower by adjusting the front end of the curve. This base rate also influences the remainder of the curve to some extent.

– They can buy assets that are of longer duration (longer-dated government bonds). Or, in the case of the ECB and Bank of Japan, they can buy corporate assets as well. This pulls down rates further out along the curve.

– When a central bank buys assets, it exchanges cash for the assets. Where does the central bank get the cash? It creates it. Where does the cash go? It goes into the financial system. If a central bank provides liquidity into the system it will get into assets, increasing their prices. This reduces their forward returns. Sometimes these returns may go negative, especially if all the liquidity in the system (private investment potential) is not able to swamp private savings.

– Negative interest rates give central banks a way to test how low creditors are willing to go on returns before pushing them into riskier assets. When growth is slowing, to keep the economy in positive shape and avoid seeing the asset and liability mix get out of whack, central banks must lower rates. This effectively favor debtors (who get debt relief) relative to creditors (who see lower returns). If forward nominal growth figures to be low – in other words, low returns expectations on future projects – then borrowers will have lower demand for it.

– Currency depreciations can also draw rates lower. This implies that financial assets will produce lower returns in the future and reduces demand for them (and hence reduces demand for that currency).

– Debt monetizations as a tertiary form of monetary policy could also be partially priced into financial asset prices. This is where debts are effectively paid off by central banks directly. In other words, they create cash and directly retire debts. This lowers implied credit risk.

– When more of the economy shifts toward less capital-intensive channels, such as the internet and other “asset light” business models, this reduces the need for capital. The largest companies in the world are not particularly capital needy firms. These include Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, Google, and Facebook. All are technology companies of some form and many parts of their businesses deal with intangible products. No longer are the most valuable companies in the world based on manufacturing or extracting resources, which require ample amounts of capital. Moreover, much information these days can be obtained for free or very cheap. It’s also easy to search the internet for the best prices rather than being stuck with only a very limited number of options within your geographical area, which keeps inflation structurally lower and also rates in conjunction.

– Forward demographic trends also reinforce the drop in growth. Real GDP growth is a function in the growth in productivity plus the growth in the labor force. In the developed world, many countries have already seen their labor force numbers peak, which means that a growing number of workers can no longer be relied upon.

– Due to regulatory reasons, many countries require their banks to hold a certain amount of sovereign debt to meet their capital requirements. (In the US, this is called a “high quality liquid asset” (HQLA) requirement.) This prevents the banking sector from becoming excessively leveraged to prevent a repeat of large vulnerabilities associated with 2008. Because banks have to buy without recourse to price or yield, the price-insensitive flow from financial institutions is a tangible source of demand and accordingly influences their prices and yields.

Compound interest flipped up-side-down

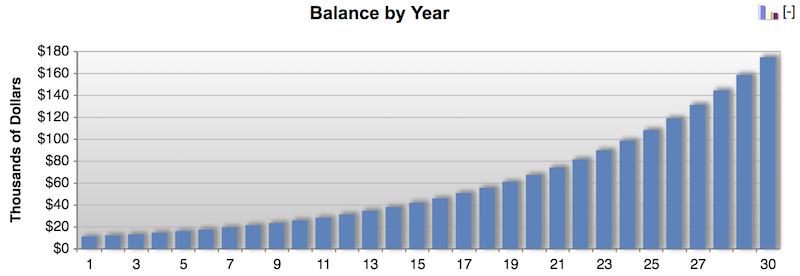

The power of compound interest allows money to grow in a steepening non-linear way. If you invest money at 10 percent over 30 years, that money grows to just 3x its amount based on simple interest. If compounded, it grows to 17x-18x its initial amount as a result of earning interest on top of the interest earned in each preceding period. Over time, this exponentiation in the growth becomes very powerful. Below shows $10,000 invested at 10 percent compounded annually over time.

However, with negative rates, this process runs in reverse. The prospect of generating positive returns from your investments or making positive returns within the context of a quality risk/return ratio becomes less plausible.

When we’re in an environment where safe assets generate negative returns, this will convince many traders that taking negative returns isn’t an option. When institutional traders and investors have a fiduciary obligation to their clients to produce the best returns that they can, this will discourage a general sense of risk aversion and encourage the continued purchase of risk assets.

This is part of the point. Central banks want to force financial market participants into riskier assets. This makes companies worth more and causes incomes and sources of potential collateral to grow. This encourages credit creation and risk taking and helps the economy grow.

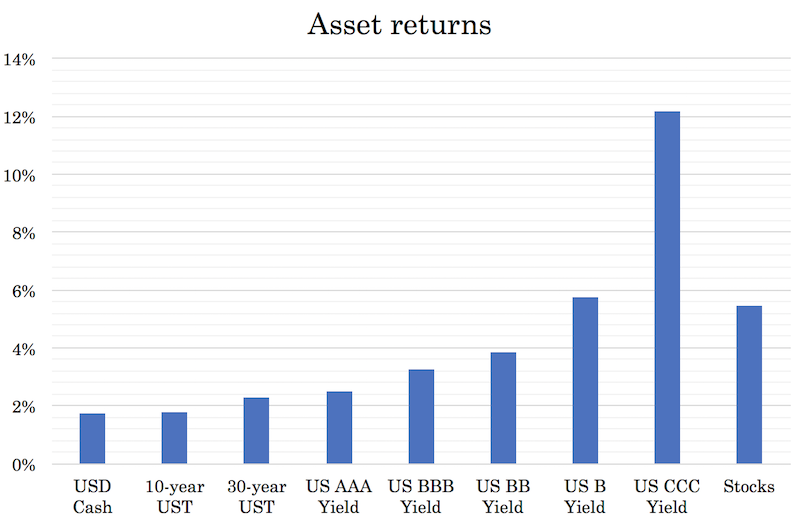

All assets compete with each other. Investors inherently want to be compensated for taking on more risk as they go from cash to bonds and from bonds (and their various types) to stocks. This also feeds into leveraged and other riskier forms of equity assets like real estate, private equity, and venture capital.

Below are how various forms of US yields compare to each other across all facets of the risk curve – cash, longer-duration US Treasuries, US corporate credit, and equities. (If we were to compare yields from different countries, we would need to adjust to keep things in constant currency terms. If we do not, the comparison isn’t perfectly appropriately because of the FX risk.)

For investors in developed Europe, this is more of an issue than for US investors, who at least enjoy some nominal return on cash (for now). Germany’s 30-year sovereign yield is roughly 0.00 percent. Italy’s 50-year yield is 2.30 percent. That’s high relative to the rest of Europe but low for a “periphery” country with some material degree of credit risk. Based on the effective duration of the bond (28-29 years), it would only take a 0.03-0.04 percent adverse change in interest rates to wipe out its entire annual yield.

Retirees who rely on the generation of income from safe interest payments may see the need to work longer or do whatever they can to save more.

Insurance companies also tend to struggle with low to negative interest rates. Part of the insurance business model is that whatever claims they pay are typically done after they receive the premiums paid in. Over that time, they generate income on this premium, termed “float”. Private insurance models will struggle if it costs them money to hold float instead. Will this require increasing public sector control of various insurance markets?

Will those who owe money be incentivized to pay more quickly if cash earns negative interest? Will those who are owed money be less incentivized to collect this money quickly if keeping it with the debtor makes them bear the negative interest instead of themselves?

How will negative interest rates impact social security programs?

In the US, the Social Security Fund can only invest in US Treasury bonds. While there is still some nominal yield associated with US Treasuries, it is very little.

If it gets worse and these eventually yield negatively like many of sovereign bonds of their European counterparts, this would pressure a system that is already facing the prospect of insolvency as soon as the 2030s.

How will negative interest rates influence the calculations of present values?

When the present value of obligations exceeds the future value of obligations (as it would if the discount rate is negative), this can be very bad for parts of the economy like pension funds. This means that present obligations that are discounted at higher rates combined with low yields on future investments can lead to low confidence of the long-term sustainability of their status as appropriately funded entities.

How will negative interest rates impact bank profitability?

Banks and lending entities largely depend on the spread between the rate at which they borrow at and the rate at which they can lend at.

This means that if the rates at which they lend at are negative, they need to borrow even more negatively to maintain a profit. This means that lowering the reserve rate below zero needs to decrease the deposit rate similarly to keep the same spread. If there is no impact on the deposit rate, then there’s no stimulatory impact on banks’ funding costs. Therefore, if the deposit rate isn’t influenced in conjunction, there is no additional willingness for banks to lend, meaning negative rates would have minimal ability to increase the credit creation of the economy and hence positively impact aggregate demand and overall output.

The impact of negative interest rates on bank disintermediation (i.e., lack of lending profitability) is part of why the ECB is trying out a tiered interest rate system to relieve some of the adverse effects of sub-zero rates.

If a bank is forced to hold loans and securities then it is essentially being penalized for lending. While bank profitability is chiefly based on the spread and not the absolute level of any given interest rate, we do see European banks as especially sensitive to interest rates. For example, here is how Deutsche Bank’s stock price trends relative to German 10-year bonds.

This suggests, that if the weighted average opinion in the equity markets is accurate, that banks are not seeing much of a drop in their funding costs from negative rates. In other words, they are not able to pass on much of the negative rates to their depositors. They’ve been able to pass off some costs of negative interest rates to corporate and high-net-worth depositors, but smaller depositors have so far been spared.

How do negative interest rates impact “black box” or algorithmic trading systems?

Because of the relative newness of negative interest rates and the unique type of relationships that they create, we have little financial history to look back on to see how different financial assets performed.

Many algorithmic trading systems are based on historical data. The problem with reliance on historical data is that when the future is different from the past these models are probably going to have an issue. There is no way traders can stress test their portfolios through negative rate environments because there’s so little precedent for them.

As a whole, traders often use the past to help them understand the present and predict the future. The idea of positive interest rates, that money has a positive time value and that compounding returns incentivizes investment, can no longer be taken for granted (not that anything necessarily should be).

How do negative interest rates impact corporate credit valuation?

If companies are paid to borrow, they not only make money by being in debt but also can effectively roll over their debt with none of the traditional associated cost.

Normally, when a company owns cash that’s a good thing. That cash earns interest to generate future income. Now that cash, if negative interest rates are applied toward it, yields negatively, so investors might be less inclined to favor companies holding it in conjunction with how much income it costs them. At the same time, leveraged companies holding negative rate debt effectively enjoy an income stream. Debt rollover also becomes easier.

In this sense, the traditional role of cash and debt are swapped in terms of the cash inflow / outflow relationship.

When various financial asset valuation models get input with a negative discount rate, the resultant valuations begin to increase in a non-linear way.

Negative interest rates and populism

How will negative interest rates affect the populism movement, which has gained steam?

When there is a large wealth gap and a large opportunity gap (or at least perceived opportunity gap), this feeds into populist sentiment. Populism is a social movement that feeds into support for political candidates who show interest in the “common people” as opposed to those who seemingly favor, or are part of, the “elite”, or those who supposedly have the political, financial, and economic system set up to their advantage.

We are now more than a decade past the 2008 financial crisis. While economies have grown again, the benefits have accrued disproportionately.

When there’s a breakdown in the social fabric of a country that can become a big issue. Even as economies are still growing and many financial markets are at or near their all-time highs, we still see a high degree of social unrest. This type of breakdown only gets worse when there’s a downturn in the economy.

Negative rates are a part of the wealth gap issue. Those who have assets have seen very accommodative monetary policy (zero interest rates, negative interest rates, quantitative easing) boost the value of their holdings. Those who don’t have assets or can only save have not seen their wealth grow at anywhere near the same level.

The negative signaling from negative interest rates

Do negative interest rates provide an inherently contractionary signal? If central banks are saying the outlook is so mediocre that the whole borrowing/lending framework needs to be upended, does this make households and businesses more pessimistic about the future?

If this is the case, then this can actually lower future growth and inflation expectations rather than raising them. It can also suggest that the economy’s rate of growth going forward will be so lackluster that instead of borrowing, investing, and spending, more consumers will actually choose to hoard instead. Eurozone household savings rates are at a five-year high.

Will the US go to negative interest rates?

Compared to Europe and Japan, the US is still in positive territory. The basic reason is that its nominal growth is structurally higher. It’s growing faster and inflation expectations are higher. The US has more growth legs to its economy than either Japan and Europe.

The US has participated in the “tech revolution” to a much greater extent. Tech is roughly 25 percent of the total US market capitalization compared to just 5 percent in Europe. Almost of the world’s top tech companies (Google, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Facebook) are based in the US. It’s also a material oil producer. Demand for credit out many years is higher, which makes sense if there are better uses of it.

The US is also not quite as old demographically as Europe and Japan, so labor force growth situation is not quite in the same type of slowdown.

Along the US yield curve, there is only 160-230bps of room left to ease. Typical easing cycles are 500bps or more. If the Fed decides to go with negative interest rates, it may be more inclined to do so after both the Bank of Japan and ECB have. The IMF has by and large recommended negative interest rates as a viable policy path.

Because the US offers higher yields that other developed markets and has the world’s top reserve currency, this has caused the US dollar to appreciate throughout 2019. A rising currency can hurt exports and cause the US trade balance to become more negative, widening its current account balance. A higher dollar can cause an unwanted tightening of financial conditions.

What to do in a world with negative interest rates?

We know that returns will not be anything like those of the past. Holding USD cash used to get you 5 percent or more per year. The same was true in other developed markets. The 10-year US Treasury often yielded 6 percent or more. Stocks have returned some 11 percent annualized over the past 50 years. Investing used to be relatively straightforward.

Now we’re in a world where USD cash gets you about 1.5 percent (and falling) and is negative in both nominal and real terms in other developed markets. Long-dated government bonds get you minus-1 percent to positive-2 percent, and stocks will give you a bit above 5 percent.

After over $15 trillion of central bank asset purchases, this has all flowed into assets, boosting their prices and lowering their forward returns.

This means if central banks get desperate enough, assets will yield negatively.

Nonetheless, there’s a limit to how negative the returns can get on cash and bonds before it no longer makes sense to hold them. At a point, investors will begin to defer to alternative store-holds of wealth and other currencies like gold. At that point, the current monetary policy paradigm of interest rate easing and quantitative easing will likely need to switch into tertiary forms of easing like currency depreciations (which are a zero sum game as they benefit one country relative to another) and the monetization of fiscal deficits.

Of course, there are always riskier assets available with positive yielding returns. There are equities, riskier forms of bonds, emerging markets, private equity, and real estate.

But these also carry high risk and these returns should be pursued with caution, as it’s difficult to find anything that isn’t already richly priced relative to its risk.

Even if your nominal return is zero on a safe asset, that doesn’t seem so bad when the 5 percent annual returns on equities can be wiped out in a couple days. Traders and investors tend to extrapolate the past into the future even when at some point that future continuing on indefinitely doesn’t seem particularly likely.

Trading in a negative rate, zero rate, and richly priced environment in general doesn’t make things particularly easy.

Conclusion

Negative interest rates give traders an additional source of uncertainty to navigate.

We don’t know for sure if negative interest rates help growth or whether they’re simply a default option that produce little marginal demand (or even work in reverse).

Do we know for sure that Europe and Japan are better off with negative rates than if they had simply been held at zero (the traditional lower bound level) with pursuit of other policies to help stimulate further? Based on their current growth rates, typically between 0-2 percent in real terms, we can’t say they’ve been terribly successful, though perhaps they’ve delayed things from getting significantly worse.

Problems with negative interest rates include encouragement of excess risk-taking, disintermediation for banks and insurance companies, potential exacerbation of some unfunded liabilities (e.g., pension funds), complications for “black box” algorithmic trading systems, difficulty in accurately valuing assets under negative discount rate assumptions, potential negative signaling effects, and continued fuel on the populism movement.

It is likely that interest rates and financial asset returns can only get so negative, which will begin to yield alternative monetary policies, such as currency depreciations and fiscal deficit monetizations, going forward.