Net Zero: What It Means for Oil Trading

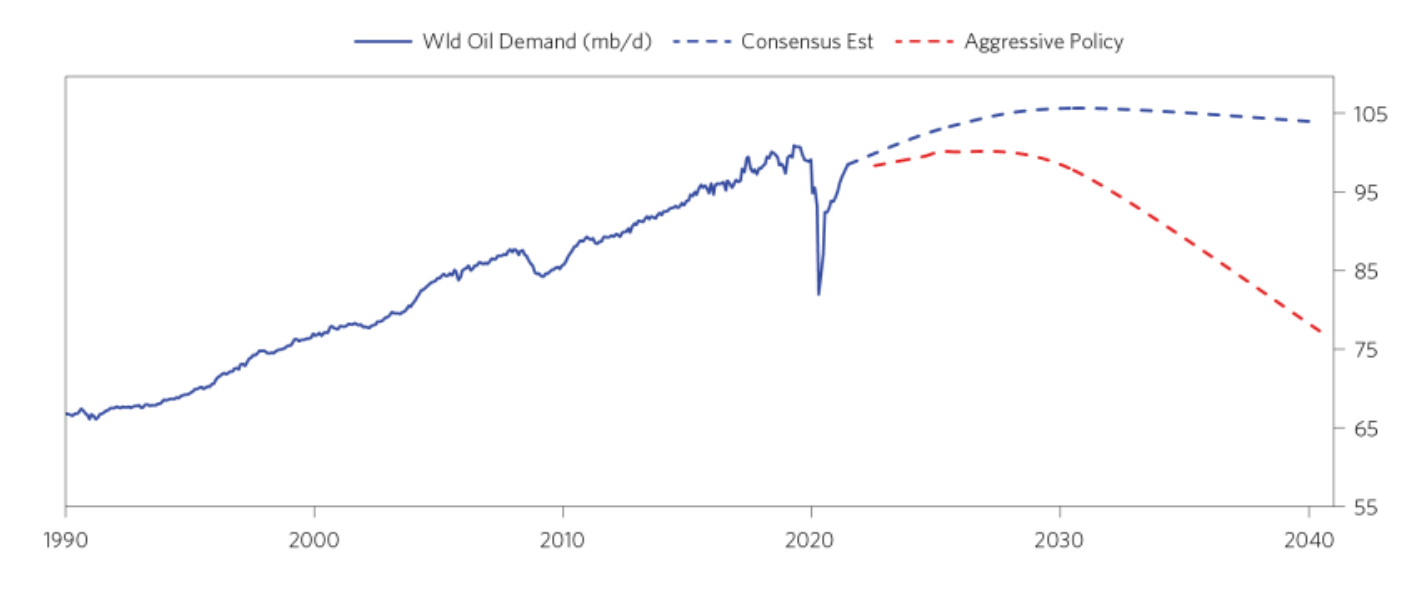

Under current policies, it’s expected that there will be no decline in oil consumption for years.

For directional oil traders, it’s important to pay attention to whether government action going forward will meaningfully reduce the demand for oil. This is likely to come through carbon taxes or subsidies to encourage the creation and shift to alternative energy sources.

The net zero concept of net zero carbon emissions by the middle of this century is growing in acceptance among policymakers and industry leaders.

Globally, more than 200 countries have signed on to reduce or cap their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in some way. This includes the world’s two largest emitters (and naturally the world’s two largest economies): China and the United States.

Under net zero, net GHG emissions are offset with net negative emissions created through the capture of waste carbon dioxide (CO2). The net-zero process can include carbon sequestration into deep underground mines or bodies of water; it can also include bioenergy generation that uses low-carbon fuels like natural gas to power transportation.

Policies adopted under net zero may ultimately materially curtail oil consumption if countries decide to pursue policies that use other energy sources to help offset carbon-intensive sources.

Most countries around the world have signed on to the Paris Agreement, committing themselves to achieve “net zero” economies by 2050. World leaders regularly meet to discuss the transition of the global economy away from emitting net new greenhouse gases that warm the planet into the atmosphere.

Discussions around net zero are very different than net zero carbon policies already in place. Under net zero, net greenhouse gas emissions are offset with net negative emissions created through the process of carbon capture.

Net zero is a concept that has been used in science and engineering for years. It can mean anything from a building, car, truck, airplane, or other piece of equipment emitting no more CO2 than it absorbs over its lifetime.

It’s important to note net zero does not mean absolute zero, which would eliminate all emissions. Net zero essentially means a net overall balance between emissions and absorption or emissions and sequestration.

Two examples come from the power sector:

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) where waste CO2 is captured at coal power plants and sequestered into underground reservoirs or oil and gas fields to enhance oil and gas production. And there’s BECCS, which stands for bio-energy with carbon capture and sequestration.

CCS technology is currently being deployed at commercial power plants in North America, Japan, Europe, China, and Australia.

In the US, it’s been used on a smaller scale at refineries where greenhouse gas emissions are offset by net negative carbon emissions.

In general, industry leaders must keep abreast of net zero technologies that can reduce demand for oil.

Institutional support for net zero

Trillions of institutional dollars have made a net zero commitment to align their portfolios with the transition of the real economy away from carbon-intensive sources of energy as well.

This net zero movement among those operating in the financial economy is led by the growing list of net zero private companies across several sectors that are committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and profiting from the global transition to net zero.

Over 500 institutional investors representing more than $35 trillion in assets have declared support for net zero policies around the world.

Assets include retirement funds, mutual funds, insurance firms, sovereign wealth funds, and increasing numbers of absolute-return vehicles like hedge funds.

The Global Investor Coalition on Climate Change (GIC), which represents more than 200 public pension plans and other investment vehicles with trillions of dollars of assets under management, has called net zero concepts “a powerful policy framework” for mitigating climate risk. GIC member institutions collectively manage more than $22 trillion in assets.

All this activity raises an important question: should traders and investors pay attention to the large stream of plans, policies, and other pronouncements on net zero policies?

Although it’s far from the only relevant aspect for market participants, this article is dedicated to looking at the question through the lens of the oil market.

Oil is the world’s largest and most studied commodity market.

It’s also the most relevant for traders and investors who otherwise don’t trade oil and commodities because of oil’s second-order impacts on stocks, bonds, and currency markets globally. Given net zero’s potential to impact oil demand, it is also highly relevant for investors in (and traders of) oil stocks.

We look at the impacts of net zero on various aspects of oil demand, which includes policy developments and net zero technologies that could become more important over time.

Net zero has only just started to emerge as an important topic for companies, energy regulators, and policymakers. But the net zero concept largely has widespread support, including among many oil majors.

Therefore, it’s important for any trader or investor to look at efforts to curtail carbon emissions in the context of the oil market.

We think the key points for traders and investors are as follows:

Governments around the world are committed to a big reduction in oil use

194 countries and the EU have signed up to the Paris Agreement. This international treaty commits its signers to achieve net zero emissions economies by 2050.

In other words, they will strive to take steps such that they will not emit new greenhouse gases – on net – into the atmosphere.

Of course, this is not easy. It will require a big reduction in how much oil is used in the global economy. This means a transition from oil to sources of energy that don’t emit new greenhouse gasses.

Many net zero targets have been set at the national or regional levels

Examples include net zero GHG (or carbon) emissions by 2040 or 2045, net zero GHG emissions on an economy-wide level by 2050, net zero methane from oil and gas production by 202X, net zero deforestation globally by 202X, net zero emissions from forestry and agriculture activities, and net zero transport sector emissions in the certain regions (like the EU).

It is important for traders and investors to pay attention to net zero guidelines as an important part of one’s long term analysis. There will be many net zero goals that may be codified into law over the upcoming decades, which in turn will impact supply, demand, and overall money and credit flows that impact prices.

In the US, it’s been used on a smaller scale at refineries where net GHG emissions are offset through the greater use of renewables or nuclear production; net zero GHG fuel standards in the US; net zero by 2050 in California and net zero by 2035 in New York; net zero for national parks in China and commitments of net zero cities across China and Europe; and by companies like Apple, Nike, and General Motors.

Work has begun on net zero standards at the international level. For example, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) is considering net zero GHG emissions from international shipping. Other potential net zero policies include net zero methane from oil and gas production globally as well as net zero agriculture.

These commitments have not yet translated to tangible policies

Many of these remain high-level commitments.

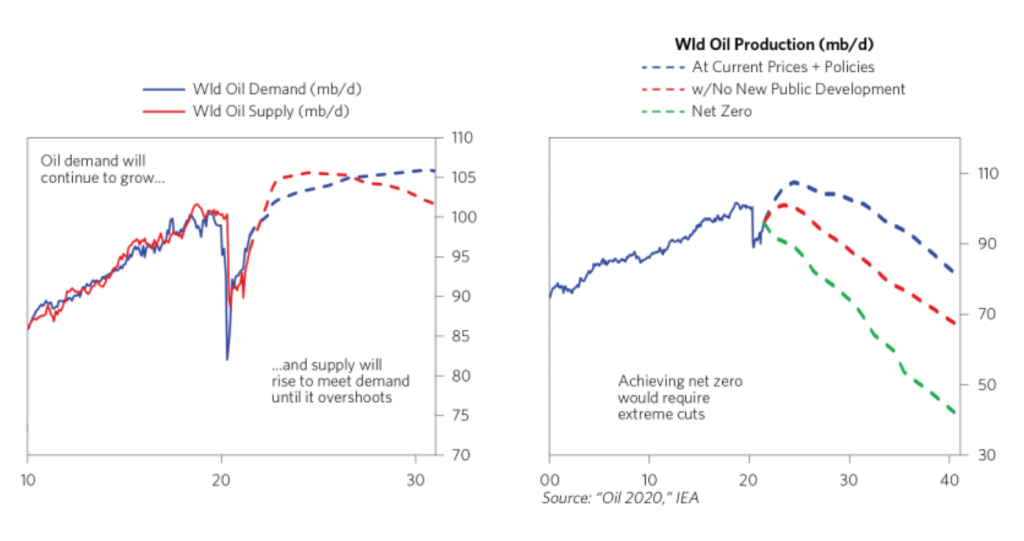

At current prices and policies, global oil use is unlikely to decline in the next decade. Oil demand is expected to rise to new highs and production is likely to rise to meet demand.

Oil consumption is likely to rise until 2030. And instead of declining from that point forward, it’s more likely to flatten.

Many net zero policies have been set as a matter of aspiration rather than policy with concrete, credible steps taken to definitively achieve these.

In the US, net zero policies are not likely to be enacted at a federal level until sometime in the 2020s.

Moreover, net zero emissions standards in the US will not start for new vehicles until 2026. And they won’t apply to existing vehicles until 2040 or later.

Further, net zero greenhouse gas emissions standards may not be adopted by states that choose to opt out of federal emissions standards. This would mean net zero compliance is unattainable under any circumstances over the next 10 years unless there’s new technology or big changes in oil demand (down).

As things are now, it appears unlikely that there will be net zero GHG emissions as it pertains to oil and gas production in the US any time soon.

China’s net zero policies could potentially become a part of a net zero economy across all sectors by 2050, but it’s unclear whether these will be applicable to oil and gas production or if net zero emissions from forestry and agricultural production will begin at any point in the near future.

Currently, China is still upping its emissions. This is true even on a per-capita basis as it grows its industrialization as an emerging economy.

It makes net zero oil trading very difficult for traders and investors to achieve over the next decade because there are no net zero standards at a global level.

Getting alignment between governments that have committed to climate change targets and have high demands for oil going forward will not be easy because of the acute trade-offs involved.

In the long term, net zero policies may lead to oil being mostly phased out as a transport fuel if adequate alternatives are dense enough, reliable enough, and economic enough to replace it.

They may be more stringent net zero policies on oil and gas production, which would have a profound impact on the oil market.

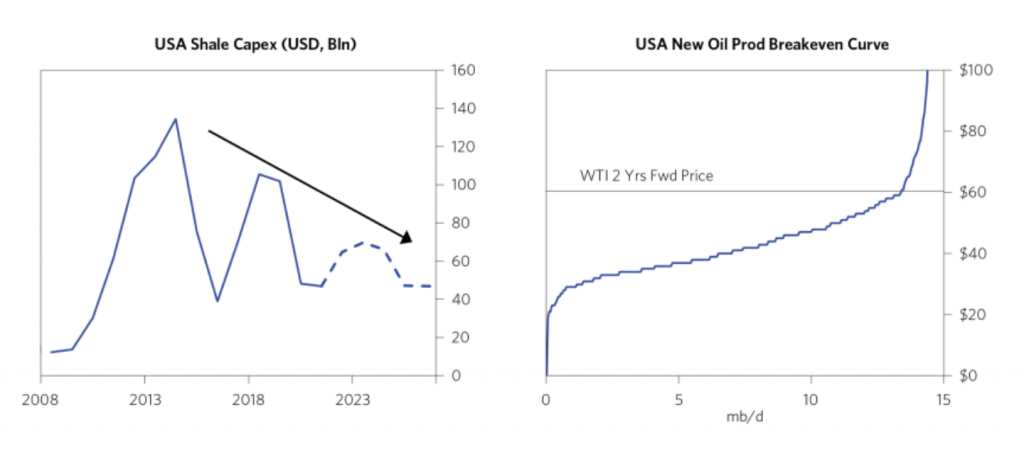

In the short run, net zero policies are likely to be net positive for oil prices because it crimps oil capex before new alternatives are ready, constricting supply and driving prices higher. We’re already seeing this.

Oil demand has been rising, which is natural with rising population growth and economic growth, and net zero emissions standards could represent a significant cost disadvantage for countries that produce large amounts of so-called brown energy compared to those that encourage renewable energy sources.

Many developed nations also got to their current level of development through the heavy use of fossil fuels, which could be considered unfair to those who may be forced to not operate with that advantage.

The dynamics of oil supply

Oil dynamics are such that it is difficult to see progress toward net zero occurring because of a shortage in supply.

Major oil producers (e.g., ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, Chevon) are committed to continuing to pump and have the pricing power to be competitive even if a lower-priced energy alternative emerged.

It is difficult to see net zero policies causing a drop in demand.

Governments and corporations will continue to seek the reliability and energy density of oil – it has high stored energy content per unit weight compared with renewable fuels. Accordingly, it should be expected for global oil demand to remain high until net zero emissions policies are adopted across all sectors globally.

In this scenario, net zero may increase costs and decrease production efficiency and competitiveness versus new technologies. NAFTA countries have increased NAFTA crude by rail deliveries since the US lifted its ban on exports in 2015. But net zero policies present logistical challenges because there exists no infrastructure for exporting renewable fuels.

Existing infrastructure will need to be adapted for net zero policies, new infrastructure would need to be built – which is dependent on brown energy today – and could require new pipelines.

Oil markets are hard to predict – which is why oil is about twice as volatile as US stocks – but net zero may cause some policy shifts in the near term while supply continues to fall short of demand as more countries explore and emphasize alternative energy sources.

There have been calls for net zero GHG emissions since the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997. But net zero is just beginning to gain global traction now because of increasing concerns about rising global temperatures and other patterns of climate change.

Traders and investors should look at what policy changes can materially reduce oil demand

If nothing changes, moderately rising oil prices in the short-to-medium term are likely as demand exceeds supply. This, in turn, would incentivize new supply to come online to meet it.

It would also mean the world is moving away from rather than toward what governments said they want to do, as stated in the Paris Agreement.

Or we could see a type of shock in markets related to the transition. In other words, policies that more aggressively look to reduce the demand for oil, by taxing carbon or subsidizing alternative energy sources.

Such policies, if they were to gain traction, would not only affect the oil market and the countries, regions, companies, and currencies reliant on it.

They would also have material influences on the broader economy. They could be inflationary or deflationary depending on the transition path that policymakers choose.

With current prices and policies, oil demand is expected to rise to new highs over the next decade. Moreover, it should be expected for production to rise to meet demand and possibly overshoot.

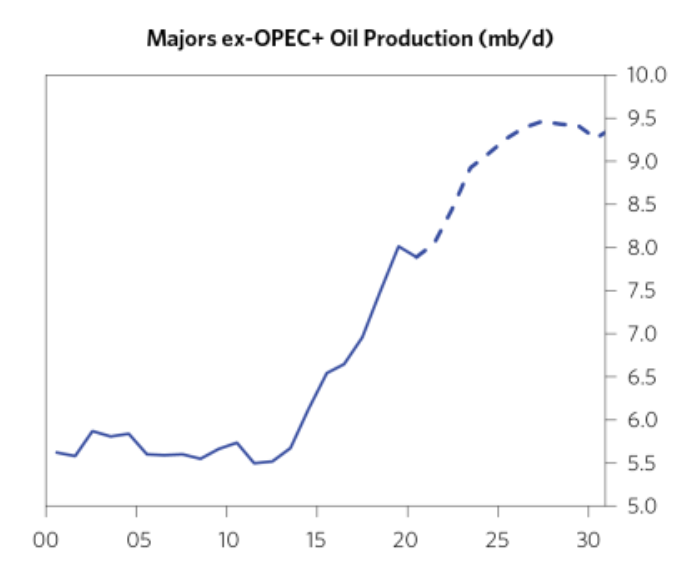

Supply cuts would have to be extreme to meet net zero goals. To give a sense of how extreme, the chart on the right below shows how far from a net zero path we would be if all publicly traded oil companies (in other words, those that are not state-owned) entirely and permanently stopped all new oil production.

Naturally, making extreme supply cuts from over 90 million barrels per day (mb/d) down to 40 mb/d by 2040 is not aligned with what they’re likely to do given their incentives.

It’s also out of line relative to their current stated goals. It would take extreme action. Otherwise, the talk of net zero by 2050 isn’t very likely.

Like with any market, it’s important to understand what each participant in it is likely to do in order to understand how supply and demand dynamics are likely to work going forward.

Oil is a global commodity, and approximately 75 percent of net oil supply comes from the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iran, China, and Canada.

Saudi Arabia is most likely to first commit to net zero emissions. It has not officially committed to that goal. However, Saudi Arabia has already worked to diversify its economy away from oil by making large investments in renewables for domestic use.

Net zero commitments would also allow the Kingdom to effectively export these technologies globally.

Oil Producers Are Willing to Keep Producing at Competitive Prices

Let’s look at the incentives of the various oil producers in the market.

OPEC+

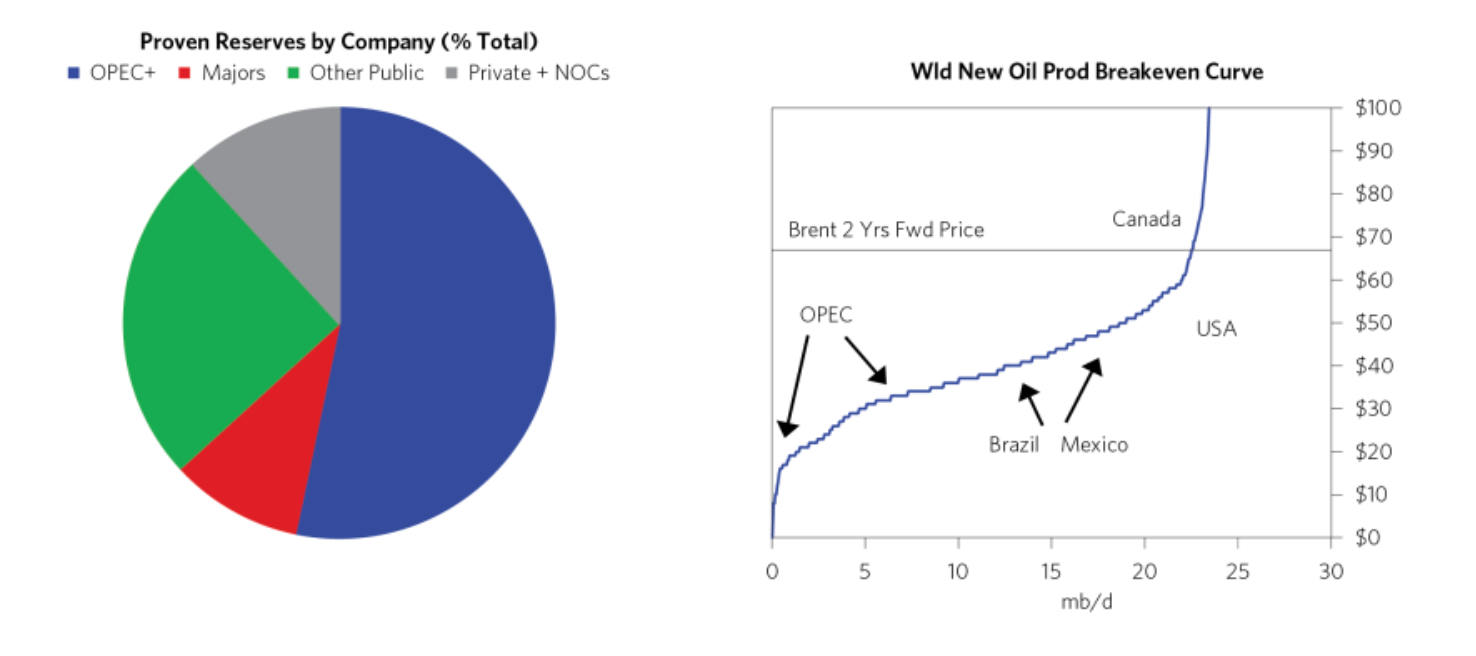

OPEC+ (which includes Saudi Arabia, Russia, Venezuela, Iraq, and 19 other countries) produces more than 50 percent of the world’s oil and controls over half of proven oil reserves.

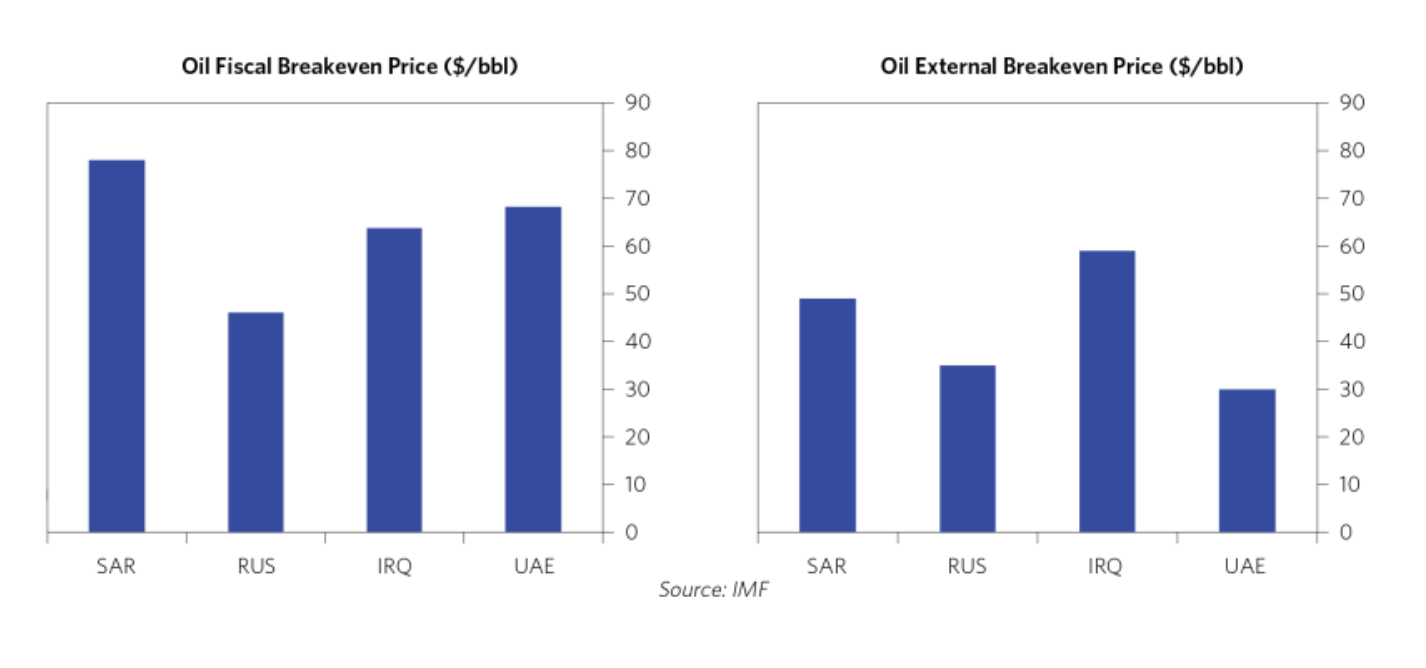

OPEC+ countries are going to want to pump oil for decades. This is because their fiscal spending depends on these oil revenues.

None of these countries have reserve currencies, so it’s not easy for them to finance deficits because of limited demand for their debt.

Moreover, OPEC+ can profitably produce at much lower prices than the standard $60 to $80 per barrel range.

So even if a strong alternative to oil emerged at a much lower price than where oil is today, they could simply drop their price to remain competitive.

Production costs are low and oil revenues are so important to their fiscal budgets, so it’s not surprising that the Saudi oil minister vowed to drill out “every last molecule”.

Norway is not in OPEC+ but is another important national producer. Its own prime minister has committed to keep drilling.

If OPEC+ could get their proven oil reserves out of the ground as quickly as needed, the contingent could supply the oil demanded by the world economy for a long time. This means there would be little progress toward zero on the supply side.

OPEC+ has some amount that they’re able to bring onto the market in the short term. But otherwise it typically takes 5–10 years to get new capacity to the market.

Other producers can also quickly work to offset supply cuts.

US shale

US shale production is unique because it can increase supply very rapidly. It doesn’t require the typical 5–10 years to bring online. Instead, it’s a more modest 7–9 months.

Most of the shale producers do little outside of shale oil. As a result, there isn’t much to persuade them to transition their business.

Before, shale producers were ramping production while not receiving return on capital. These days, they can invest in new projects while still producing a profit and having positive cash flow.

Today, they’re likely to have a strong incentive to push production forward if prices rise to incentivize production.

Oil majors

The publicly traded large oil companies that receive widespread shareholder attention are about 10 percent of the total global oil market.

Oil majors are vulnerable to shareholder actions and the most able to push into other businesses given their market capitalizations.

But they are also a small share of the overall oil market. They would need to make extreme cuts to their output to have much impact on the global oil scene.

Altogether, given global producers’ current incentive structure, it is not likely that there will be a material and sustained lack of supply that pushes oil consumers to transition to alternative energy sources under current policies.

However, developed market players reducing new oil capex does indeed has an impact. Any reduction in the capacity to pump oil tightens the supply/demand balance at the margin.

But supply cuts are only meaningful if other players don’t come in with their own production to simply offset another’s supply cuts.

As shareholders look to cut down on new oil exploration, more oil and gas capex shifts to private companies that are out of the public limelight.

Moreover, countries with large proven oil reserves like Saudi Arabia, Norway, and other have insisted on their intention to keep drilling.

Higher taxes and/or regulations on US shale production would have the largest impact, given their role as a marginal supplier to quickly fill in any gaps in the market.

Without actions taken to disincentivize US shale players from coming into the market to take advantage of high prices, shortcomings in oil supply relative to demand are likely to largely be met by US players coming in with their own production.

This is likely to limit price increases and therefore limit the incentives to shift away from oil.

So, what does net zero actually look like?

What’s Happening in the Oil Market Today Illustrates How Supply Cuts Don’t Reduce Global Oil Consumption

That is, unless the supply cuts are massive and permanent.

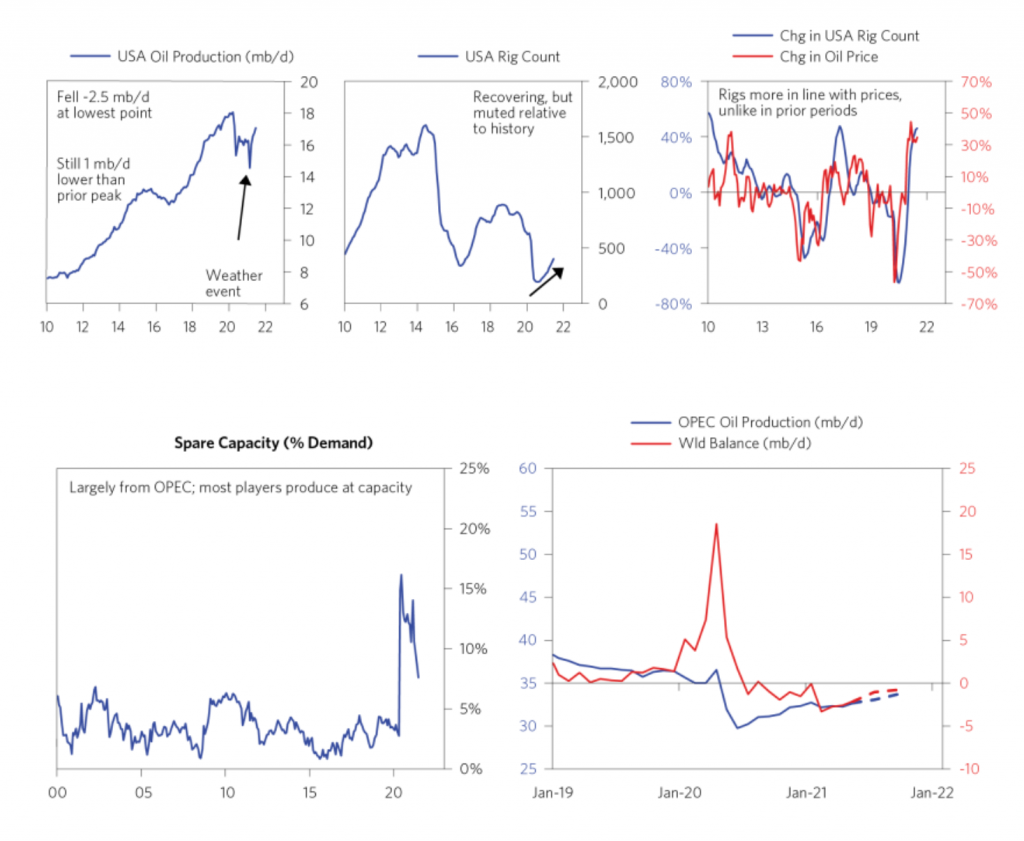

In 2021, US oil production fell markedly and didn’t recover to its prior highs.

But global oil consumption wasn’t impacted much. OPEC+ simply scaled up their production to fill in the gap and continue this production to match the recovery in demand.

Oil prices may have been somewhat lower if US supply had been higher. But this has kept oil prices below the point of encouraging any transition away from oil.

Moreover, total oil consumed was not affected by cuts in US supply.

This shows that for supply cuts to matter, they need to:

a) be large enough to more than make up for all the spare capacity from OPEC+ and

b) not incentivize more US shale production

OPEC+’s incentives, as they’ve come out and confirmed, have been to increase oil prices while maximizing volume amount to maximize revenue to support their fiscal spending.

To maximize revenue, OPEC+ wants the highest possible prices but without:

a) incentivizing the higher-cost producers (like US shale) from entering the market to capture more share or

b) accelerate the transition away from oil.

This means they want prices around $75 per barrel. This is plenty above their production costs and allows them to maintain their current level of fiscal spending.

US shale is one of the only producers capable of ramping up new supply very quickly, in under a year.

Reduced US supply has heavily been driven by producers’ desire to prioritize returns to shareholders and avoid taking on too much debt relative to free cash flow.

But as supply thins out, this provides strong incentives to increase drilling again.

As shown in the charts below, US oil production give high net margins at today’s prices.

Shale companies don’t have the usual trade-offs that they would otherwise have at lower prices. Namely, they can both maintain capital discipline and avoid over-leveraging and expand production at the same time.

This can effectively cap any price pressures from reduced supply via other sources.

Most shale producers have little to no reason to keep going if not to drill for oil. So shareholders in these companies are not likely to strive for supply cuts that would make any material difference as it pertains to net zero goals.

On the other hand, the oil majors could more feasibly shift their businesses toward alternative revenue streams – and have had some shareholder pressure to do so.

But their current plans don’t involve any material cuts to oil supply going forward.

ExxonMobil and Chevron still have ambitious growth targets, especially in the Permian. ConcoPhillips wants to drill 4,700 wells in the Permian over the next decade. This would be more spuds in operation than any other Permian producer since 2014 (when oil and gas capex peaked relative to production).

Industry producers have been increasingly using net zero concepts to describe how they’ll go about reducing their carbon emissions and increasing investments in alternative energy.

Net zero has also been used by oil companies when discussing plans to replace volumes due to production declines.

Net zero means that US shale producers will have a large enough role in keeping supply in line with demand that there won’t be a material impact on price due to supply cuts elsewhere.

Supply provided by OPEC+ will have a vital role in filling the gap left by reduced US oil supply, with little influence on prices or total global oil consumption looking forward.

Current Policies Aren’t Likely to Lead to Meaningful Cuts in Oil Demand Either

Consumers (households, businesses, and so on) will have less demand for oil if it’s expensive relative to other energy options.

Oil consumers also want to know the trajectory of future prices.

In other words, are high prices likely to be sustained or short-term.

This matters as it pertains to potential investments involved in switching. For example, it matter in terms of what it takes to power a car, new building, factory, and so on.

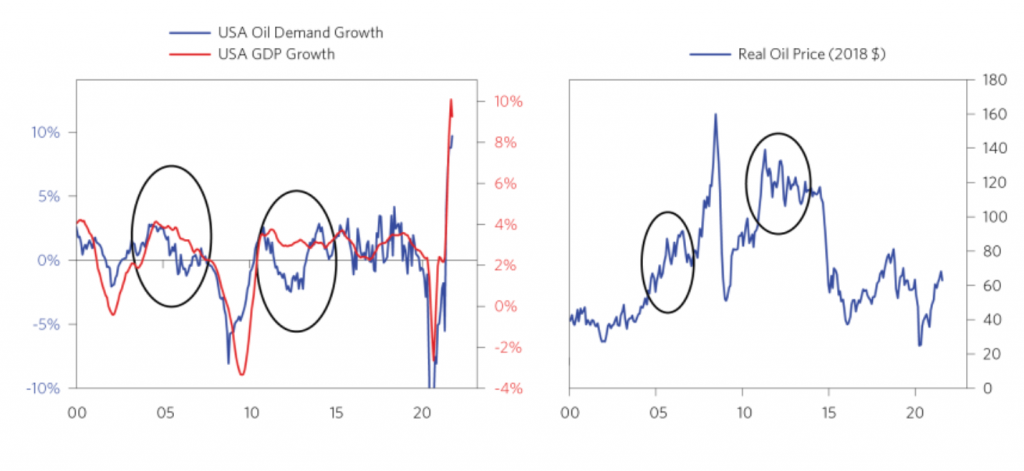

This means that in the short term, it would take large jumps in the price of oil to cause demand to be materially reduced.

Therefore, oil demand is not likely to be hit much directly through the free market/private sector.

Demand is more likely to fall through policy action, such as taxes or subsidies or through the development of cheaper alternative sources.

A drop in supply makes oil more expensive. This means more revenue goes toward producers.

Carbon taxes make oil more expensive for consumers but not producers, but with the revenue going to governments, who can then redistribute the money back to consumers or invest in new alternatives.

If oil is expensive from curtailed supply, this encourages new suppliers to come in and take advantage of the higher revenue. This could be from privately-held companies who are less vulnerable to shareholder pressure on responding to climate change. This has been seen in the oil recovery from the Covid-19-related bust.

If oil prices fall because of taxes or cheaper alternative energy sources, not as many suppliers will want to enter the market. This makes price increases to consumers more entrenched.

It’s not easy to make any type of dent in oil demand quickly. The charts below show oil price levels over recent history that have been needed to begin shifting away from oil.

In the past time, we’ve seen oil demand fall (relative to economic activity) when oil prices went above $85 per barrel (or somewhat above).

But those price increases weren’t believed to be permanent (and they weren’t). So new investments in shifting away from oil didn’t make sense given the temporary nature of the price shifts.

Aggressive public policies can accelerate a shift away from oil.

But oil demand is still likely to grow. Any type of shift in that pattern isn’t likely before 2030.

Some changes that were made as a result of Covid-19 will make a small dent in demand. Electric vehicle adoption may be accelerating and policymakers are offering big incentives to get people into them, but don’t move the needle much (and a lot of electricity used to charge electric vehicles is produced through fossil fuels).

The big thing for traders and investors to look out for is a type of transition shock. This is where policies more aggressively reduce oil demand either by pricing carbon or subsidizing greener alternatives.

If these kinds of policies emerged, they would not only have a material impact on the oil market and the companies, countries, and currencies dependent on it.

They would also impact the wider economy, because they may be inflationary or deflationary depending on how policymakers choose to make the transition.

There are two main initiatives that traders and investors should be looking at that could impact this picture:

1) What oil alternatives are being favored?

One example is government subsidies and incentives forcing more of a shift to electric vehicles.

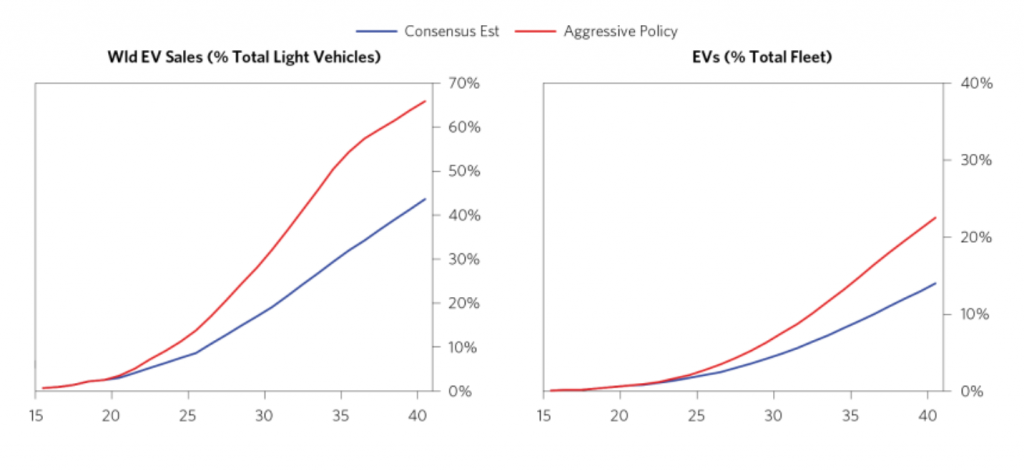

The transition to electric vehicles is just starting. And it will likely take time for the global fleet of vehicles to turnover more toward EVs. (Cars are lasting longer as automotive technology improves their lifespan.)

Aggressive rules could create a significant shift in demand.

In Europe and some political circles in the US, there is more talk about when to abolish cars and other equipment (even lawn mowers) with internal combustion engines, which reflects the scope for increased action.

For instance, carbon taxes in the US and EU could accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles.

That is, faster than they’re already being brought to market by some startup auto producers. And increasingly by big legacy auto OEMs who are eating more of the startups’ market share as they become more economically feasible to produce (e.g., VW, GM, Ford).

The net impact of these policies may not be net negative for oil prices.

But they will, however, create net positive demand for alternatives to oil if adoption of these products accelerates.

On the other hand, if governments are more slow to definitively act on net zero and other climate policies, price increases could be more likely. This is especially true if geopolitical risk increases. Higher prices will still encourage the production and adoption of other sources of energy even if actions by governments don’t add up to much.

The earnings of oil companies can be volatile depending on oil prices, drill bit performance, regulatory matters, weather patterns, and other factors that are beyond traders’ control or a horizon on which they could make reasonable predictions.

2) Taxing carbon/CO2 emissions

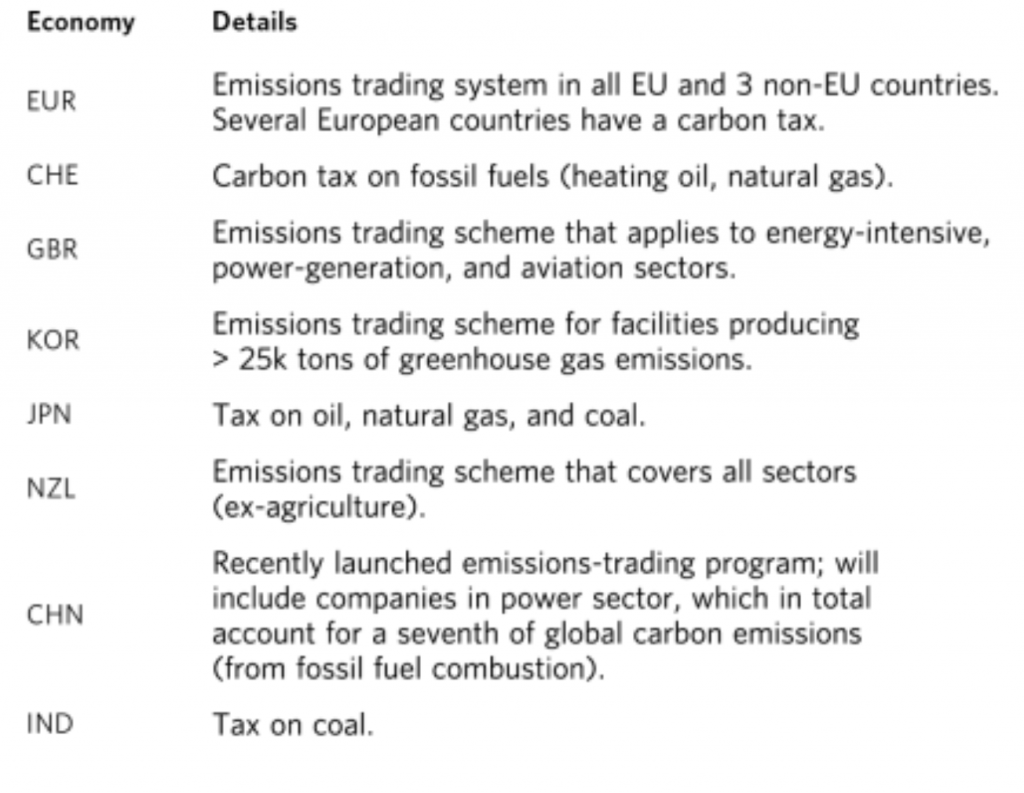

A broader approach for governments is to implement a tax on carbon emissions.

If oil prices for consumers increase due to taxes, price increases are likely to seem more entrenched.

In turn, this could help accelerate the transition. Businesses could deem with more certainty that it’s worth it to invest in transitioning if they need to pay for carbon or GHG emissions certificates every time they use oil.

There are more carbon pricing schemes coming into play, mostly in wealthier developed nations.

But progress toward meaningful carbon pricing is fairly slow.

Carbon taxes and emissions policies

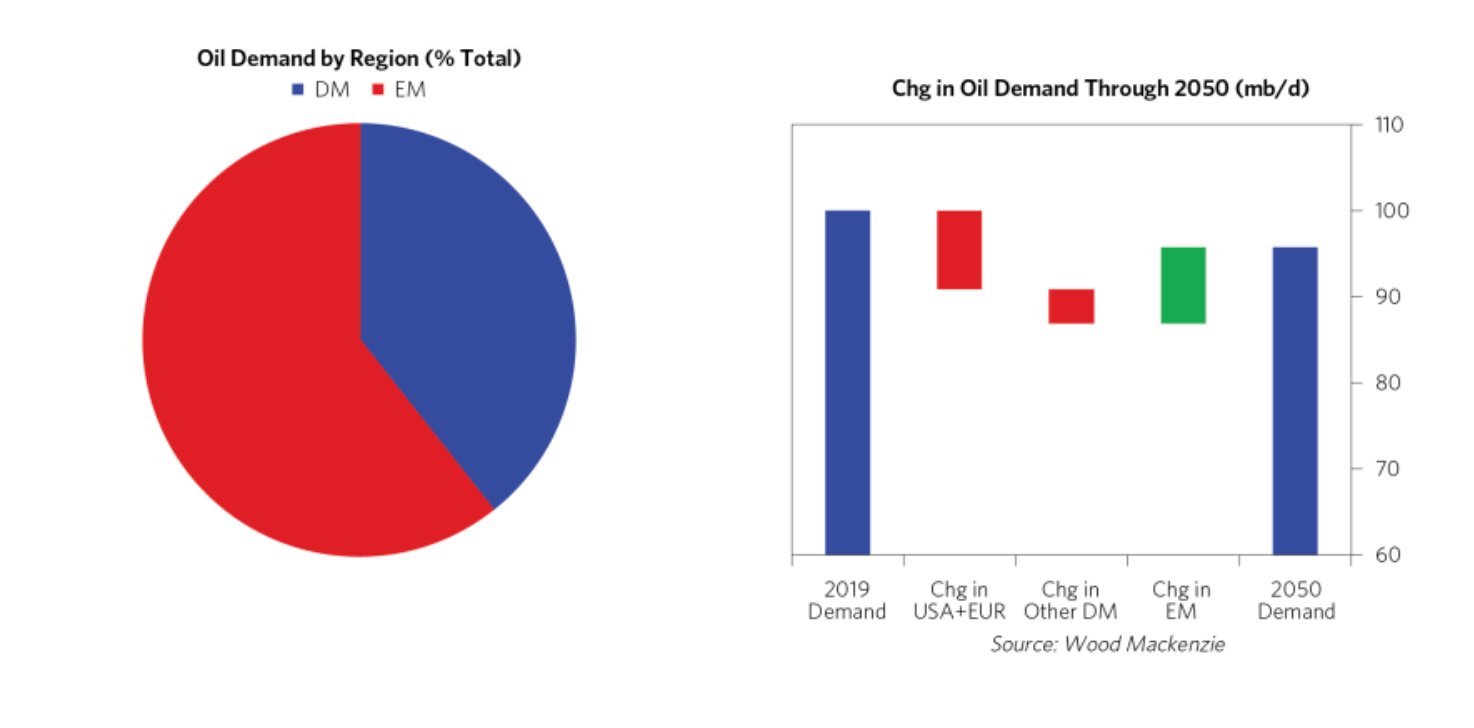

While most progress toward policies aimed at reducing oil demand is in developing countries, more than half of global oil demand comes from emerging markets.

Moreover, all of the projected growth in oil demand looking forward comes from emerging countries.

This means that most of the oil demand is coming from parts of the world where carbon taxes aren’t very likely to be adopted.

As oil demand falls in wealthier countries, the OPEC+ producers will be incentivized to keep producing oil and place prices low enough to disincentivize consumers from switching.

Having carbon taxes only in Europe or in other wealthier countries won’t be sufficient unless it leads to the development of cheaper energy alternatives to oil that are then economic for all countries to adopt.

By this point, what happens with oil – demand, supply, and prices – depends on how incentives are and this is likely decades down the line.

There’s likely to be lower oil demand in rich countries, but it depends on how things play out in emerging countries where greater industrialization is creating more demand for energy.

It’s also unknown where OPEC+ economies are in 20-30+ years:

- How dependent are their economies on oil revenues to support their spending?

- How well did countries diversify their revenue streams to reduce reliance on oil (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iran, Venezuela)?

Net global production capacity is not likely to change much over the next few decades. And neither is output when OPEC+ producers can pump oil profitably down to very low levels (much lower than oil majors and shale producers).

A net positive demand shock for oil would likely need to come from emerging markets where oil demand growth is still high (and accounts for virtually the entirety of oil demand growth).

Moreover, political opposition to carbon pricing may be higher than in wealthy countries. This is because poorer countries have more building to do and want to take advantage of the most economical sources of energy possible to make this a reality.

There is a risk that falling prices will actually stimulate demand growth if consumers (households, businesses, countries/governments) think low prices are persistent.

New energy technologies could work to lower net global supply. But it could also come from environmental policy action resulting in net negative emissions shocks – e.g., higher carbon taxes, stricter emissions standards, or lower energy demand (due to higher efficiency, limiting use of fossil fuels).

Risks to the outlook

1) Black Swan Events

Oil prices briefly went negative during the Covid-19 crisis due to a big slowing in transportation and industrial activity.

For example, if new short-term US supply sources were to become available in combination with a demand shock lower (or one or the other) it could reduce oil prices significantly and lead watchers of the oil market to lower their net baselines over time.

Low probability scenarios and tail risks are always worth monitoring.

For example, viruses and pandemic-related risks should mostly be in the rearview mirror.

But oil is still extremely sensitive to potential virus issues given the potential for travel restrictions, lockdowns, and general fear of traveling if there’s a flare-up.

On the Black Friday shopping holiday in November 2021, news of the B.1.1.529 omicron Covid-19 variant drove WTI oil prices down more than 13 percent in a single trading session despite many traders having the day off.

2) Acceleration of decarbonization

More aggressive decarbonization policies than expected by governments could result in net negative emission shocks. This could produce more fuel switching than anticipated.

Can Renewables/Clean Energy Take Over for Oil?

The technologies and infrastructure to begin to make renewables a substantially larger part of the energy mix aren’t developed yet and inadequate investment in the standard primary energy sources alongside them in the interim has created a supply/demand imbalance in those markets, so the transition is being done in an inflationary way.

A lot has to be accomplished in order to get a material change in the energy landscape while also counterbalancing the current supply/demand issues.

That’s why some parts of Europe and Japan, especially, are looking to reactivate nuclear plants to better ensure that energy supply can meet energy demand to avoid/reduce cost inflation, given solar, wind, and biofuels aren’t ready yet to absorb the shortfall.

And there’s also the matter of how the energy problem feeds into their current macroeconomic problems in Europe with inflation rates so well above ECB targets at the same time they’re running into growth problems.

So it’s an extreme challenge and it is not easy dealing with the reality of those trade-offs.

And the outcomes for clean energy’s impact depend heavily on how well those investments are done because there’s an extraordinary upfront cost that has to be borne by society today and in the years ahead (depending on how aggressive the policies are) plus a long lead time to realizing the benefits.

Are they establishing clear and impartial metrics to objectively assess how those investment programs are going – i.e., to ensure the outcomes and progress toward the outcomes are providing benefits at least commensurate with the costs?

Added up over the past two decades, the cumulative subsidies across the world for biofuels, wind, and solar approach about $5 trillion to supply roughly 5 percent of global energy.

The world still depends on hydrocarbons for 84 percent of all energy, which is just two percentage points lower than 20 years ago.

Electric vehicles’ offset to world oil demand rounded to the nearest percentage is still zero percent.

Such policies like “net zero by 2050” also don’t entail going to zero world oil production.

But steep cuts would be necessary that would be highly inflationary if there isn’t offsetting equivalent energy supply to fill the gap.

To achieve that sort of goal (which is very unlikely to happen for various reasons) would mean world oil production would need to fall from ~100m barrels per day equivalent now to around 70m b/d by 2030 and around 45m b/d by 2040.

On average, the US has about 1-2 months’ worth of national demand in storage for each type of hydrocarbon.

Those quantities are possible because it costs less than $1 per barrel per month to store oil or the energy equivalent of natural gas. Storing coal is even less expensive.

Our current electricity grid that reliably powers nearly everything in most parts of the country costs less than 3 percent of GDP.

Storing electricity itself in terms of the output from solar/wind machines remains extremely expensive despite advancements in battery technology.

Lithium batteries are around 400 percent better than lead-acid batteries in terms of energy stored per unit of weight (which is important for vehicles).

The costs for lithium batteries have declined more than 10-fold in the past two decades, but it’s still at least $30 to store the energy equivalent of one barrel of oil using lithium batteries.

That’s why, regardless of mandates and subsidies, batteries aren’t a solution at grid scales for days of storage, let alone weeks or months.

Global Growth in Energy Demands

And it’s not only how much energy the world currently uses, but how much more energy the world will demand going forward.

It takes nearly as much energy to make a single smartphone as it does one refrigerator, even though a refrigerator weighs 1,000x more.

And the world produces almost 10x more smartphones each year than refrigerators.

This means the global production of smartphones uses 15 percent as much energy as the entire automotive industry.

Global cloud infrastructure, a relatively new invention that’s still growing rapidly, already uses 2x the electricity as the entire nation of Japan.

And then there are all the other common, critical needs for energy – heating, cooling, food production, delivering freight, and so on.

In terms of other types of statistics to show where energy demands are going:

- In the US, there are nearly as many vehicles as people, while in most of the world, less than 5 percent of people have a car.

- More than 80 percent of the world population has yet to take a single flight.

Wind, solar, and EVs have not yet come even close to cost parity with traditional energy sources or modes of transportation.

Even before the latest period of rising energy prices, Germany and the UK, which are both further along in transitioning their grids than the US, have seen average electricity rates rise 60 to 110 percent over the past two decades. The same pattern is happening in Australia and Canada. This is also going on in US states and regions where mandates have resulted in grids with a higher share of wind/solar energy.

In general, overall US residential electricity costs rose over the past 20 years despite an average overall decline in the cost of the inputs (natural gas and coal) over that period – the two energy sources that supplied nearly 70 percent of electricity over that time.

Rates have gone higher because of new spending on infrastructure required to transmit wind- and solar-generated electricity, in addition to the increased costs to keep electricity flowing during periods where wind and sun aren’t available that come from also keeping conventional power plants available.

Conclusion

There are many potential opportunities that would put upward pressure on net global supply (OPEC+ production, US shale) that could cause countries to fall well short of their net zero goals.

To reach net zero by 2050, there needs to be around net-zero demand (not zero demand, but net-zero via offsets through carbon capture, sequestration, and other methods of pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere).

This is likely either through net negative carbon pricing shocks or through net-negative supply shocks resulting from environmental policy action to accelerate the process of decarbonization.

As oil demand falls in richer countries, OPEC+ producers will be incentivized to keep producing oil and push prices low enough to disincentivize consumers from switching.

So, for supply cuts to matter, they need to be large enough to more than offset OPEC+’s spare capacity and not incentivize additional production from US shale.

OPEC+ wants to have oil prices as high as possible while maximizing production in order to support their fiscal budgets.

This means high enough, but not too high to avoid US shale from drilling more and taking up more market share.

And also not too high to incentivize consumers (households, businesses, etc.) to shift away from oil.

This is somewhere around $75 per barrel, though it changes over time depending on the dynamics of the market. This is above their production costs and enables them to keep spending without going too far into deficits that would otherwise be difficult to finance (due to their lacking of a reserve currency to help support large amounts of debt issuance).