How To Buy Cheap Stocks In Any Market

The concept of the cash-secured put, or selling put options for income, is one method traders of all stripes (individual, institutional) will use to generate income and/or buy securities cheaper than the current market price.

The buyer of a put option pays a premium to the seller for the right to sell shares at an agreed upon price in the event the option lands in the money (ITM). Each option contract contains 100 shares of the underlying stock.

If the seller holds to maturity, he will receive the premium. If it expires out of the money (OTM), he keeps the entire premium. If it expires ITM, his profit is the difference between the premium and loss based on the relative “money-ness” of the option.

For example, if a seller writes (“writing” options is another name for selling) a 100 strike put on an option for $6 per share ($600 per contract), and the underlying security finishes at $95 by expiration, it finishes ITM by $5 per share.

The seller’s profit is then $6 minus the $5 loss, or $1 per share. Moreover, he buys the shares at $100 each, which is part of the contractual obligation of selling an option.

Why sell options?

Traders who sell options will do so for various reasons. It may be part of a broader strategy that has multiple legs to it. Advanced options strategies, such as call spreads, put spreads, iron condors, and iron butterflies, will often involve a trader selling options.

They may be short the stock and wish to cover at a particular price lower than the current market price. Similar to a covered call for a long position, a covered put can provide the same type of function for short positions. It also has some level of hedge value should the short position go against them.

They might also feel the price of a stock is too high. Accordingly, a trader who is short puts may wish to buy at a lower price and get paid to wait.

If a stock is $120 per share, and you feel it’d be a better value at $100, then selling a 100 strike put option is one opportunity to get paid a premium while you wait.

Note that selling options is risky. To go along with concentrated positioning sizing and the uneducated use of leverage, selling options is one of the most common ways traders punch large holes in their portfolios.

Unlike the buyer, who can lose only the premium paid for the option, the seller of the option bears the entirety of the downside. Selling a call option entails potentially infinite downside, while selling a put option involves the downside of the security going to zero (not unlike owning a stock).

This is why puts should be cash-secured. If you are selling, for instance, 10 contracts of 100 strike puts, you know that those 10 contracts cover 100 shares each. That’s 1,000 shares. One hundred shares at $100 each (the price you would buy at) represents a potential $10,000 purchase cost.

How much margin you have to post to cover that will depend on your account – i.e., cash account, Reg-T, portfolio margin, etc. Securing your position with cash is the safest way to go.

The downside with selling puts is that as the position goes against you, your broker will require you to post more margin against the position. That means if you don’t have the margin available in your account, you could be squeezed out the position because of the need to raise cash. It’s hard to grow your portfolio over the long-term if you constantly have to liquidate losing positions because of a cash shortage in your account. This is the opposite of what you want to do because you’re effectively selling at more favorable prices (relative to when you got in the position).

If you have a margin account that requires you to post 25 percent collateral for each cash equity position, your broker will only have you post a fraction of your potential purchase price if the option you sold is OTM. But if that option starts to go ITM, your broker will automatically have you post more collateral.

It’s important to have that on hand to avoid having to sell at the most inopportune times.

It’s tempting to run one’s liquidity buffer down to very low levels to remain “fully invested”. But there needs to be enough to tolerate any down swings in your portfolio. If you use leverage, basic hiccups in your net liquidation value can give you problems with liquidity management.

In down markets, you ideally want to be the one picking up anything trading at discounts. You don’t want to be stretched such that it forces you to be part of the selling because you were over-extended and need to raise cash to cover margin deficits.

When to use the cash-secured put strategy

If you want to own a stock, but it’s too richly priced for your current tastes and want a higher margin of safety, you could consider selling cash-secured put options at a strike you’d feel comfortable buying it at.

This allows you to collect a premium either way while allowing you to potentially buy the stock at a cheaper price.

The closer ITM the option is, the higher the premium will be and the greater the probability the stock will be assigned. The further out from expiration, the higher the premium will be, holding all else equal. What constitutes a quality return is up to the individual and is what makes a market.

Example

Let’s say you like the long-term prospects of Facebook (FB). If you find the current price too high, you could consider a cash-secured put against the stock.

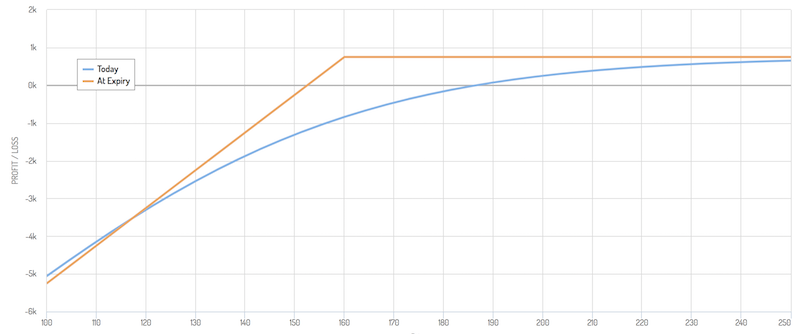

If you wanted to sell a 160 strike put with a ten-month maturity, your premium would be about $750 ($7.50 per share), with an upfront collateral requirement of $2,322.

If the option lands ITM, a 160 put would require you to buy $16,000 worth of Facebook stock by expiration ($160 per share multiplied by the 100 shares per contract).

If you’re in a margin account that has a 25 percent margin requirement, you’d need to post up to $4,000 in margin (.25 multiplied by $16k). Because the option is currently OTM, you’d be required to post only a bit more than half of that currently ($2,322). Nonetheless you should be sure that you have at least this amount on hand.

Your breakeven on this trade is the strike price minus the premium per share – $160 minus $7.50 or $152.50.

If the stock is currently $200 per share, that means over the duration of this trade, you would be profitable so long as the stock doesn’t fall more than 24 percent (1 – $152.50/$200), with a maximum profit achieved so long as the stock doesn’t fall more than 20 percent (1 – $160/$200).

As you can see, if you’re short the put, you have a fixed upside (the $750 per contract) and large downside if shares were to go down a lot. Your probability of getting the full $750 is quite high because generally stocks don’t fall 20 percent (and stay there) within ten months.

The implied probability is about 75 percent of getting the maximum profit on this trade as the seller. (A free options probability calculator can be found here, using the variable inputs of the current stock price, target stock price (i.e., strike price), number of calendar days remaining, and the implied volatility of the stock, which can be found within most brokerage trading software.)

However, prices can and will go against you, and such bad events are fully within the range of expectations.

Some traders never want to “short gamma” (sell options) because of the limited upside and unlimited (or very high) downside structure to these types of trades.

When you short OTM options, you will tend to have a high win percentage. But when you lose, you can lose many multiples of your premium. When shorting options, it tends to about balance out in terms of profit and loss with frequent small to moderate wins punctuated by infrequent large losses. The upside of selling puts is, as mentioned, the ability to own a security at a cheaper price.

As a seller, options do lose value over time, which is positive when you’re on this side of the trade. However, things change as time passes. Namely, price and volatility of the underlying security also change.

When you’re going out ten months on an option, like in this example, that is a long time and will carry a large amount of time premium. The prospects of a company could change, and naturally so could one’s opinion. Even though $160 per share on Facebook seems cheap now, if something transpires (with the economy, with the regulation of tech firms, with Facebook specifically, and so on), that might not seem like such a good deal.

The pricing of an option is a function of its implied volatility (commonly abbreviated IV) relative to its realized volatility.

If implied volatility is higher relative to realized volatility, the option’s seller makes a profit (on the option itself). If implied volatility is less than its realized volatility, the option’s buyer makes a profit.

Disregarding the effect of realized volatility on an option’s price often leads to the faulty conclusion that theta decay will be a strong source of investment income. Theta decay has value if the option is priced expensively relative to its intrinsic value. If the option is priced inexpensively (i.e., implied volatility lower than realized volatility), then theta decay works against the seller.

Conclusion

Selling cash-secured puts is one way to buy stocks more cheaply than you’d otherwise be able to. A put option gives you the right to buy a stock at the strike price if it lands ITM. If the option expires OTM, you won’t have the opportunity to buy the stock at the strike price, but will receive the premium.

In one way, selling cash-secured puts allows you to place a buy limit order on a stock that you’d like to own while getting compensated for doing so. If the options are assigned, the premium can partially or fully offset the mark-to-market losses on the stock.

In our above example, if you paid a $7.50 per share premium to get into a 160 put on Facebook and the stock was $158 by expiration, you would have a $2 per share mark-to-market loss. But the $7.50 per share premium would more than offset the loss. You would earn $5.50 per share and get the benefit of owning the stock about 20 percent cheaper.

Always be sure to have a sufficient capital cushion to not only afford the required collateral you need to post, but also the collateral that will need to be posted if the shares decrease in price. If you are in a cash account and can sell options, you should have the full purchase amount in cash to “secure” the put. For a Facebook 160 strike put, that means $16,000, given 100 shares per contract. For a margin account, it will be lower and will be dependent on the type of margin account you have.

If you don’t have an adequate capital cushion, this puts you at increased risk of having to go through a margin call if and when the underlying security goes down in value. Running it too close with your excess liquidity can get you into the dangerous, wealth-sapping dynamic of needing to “sell low” in order to raise cash. Doing the opposite of what you need to do (sell when it goes in your favor and buy when the price is right) makes it very difficult to succeed at trading over the long-run.