The Four Main Ways to Alleviate Debt Crises

Below we’ll go through the four main ways debt crises can be rectified and how these levers are normally used.

Debt defaults and restructurings

Getting rid of bad debts – i.e., debts that won’t produce more than they cost – is vital for the future flow of capital and for a return to good economic times.

The major challenge for policymakers is to enable that process to work itself out in an orderly way to ensure economic stability and market function.

The challenge for traders is anticipating what’s likely to play out ahead of time. Moreover, they will need to recognize what they don’t know (which will be a lot) so they can be largely immune to them through strategic diversification and smart asset allocation.

Debt crises that are the best managed are those where policymakers:

i) quickly recognize the magnitude of the debt problems

ii) restore or create new lending infrastructure to enable creditworthy borrowers to get access to credit in the future

iii) don’t save every institution that is not essential, enabling insolvent institutions to fail and restructuring the risks that such failures can have on other lenders and borrowers that are creditworthy

iv) enabling acceptable growth and inflation conditions through a combination of lowering interest rates, buying assets, and/or providing credit and liquidity support program where necessary

v) ensuring adequate stability in the currency

With respect to longer term considerations, will policymakers change the structure of the system to repair the root causes of what created the debt problems?

Or will they choose to restructure the debts by writing them down and spreading them out over the population such that they are not unbearable?

This process takes time to figure out. Things happen fast and the flow of information is imperfect.

Policymakers are normally slow to react and don’t understand the magnitude of the problem at first. Instead, they will settle on one-off measures that are typically not adequate to do much outside a temporary boost (if it is not underwhelming relative to expectations).

For example, during the onset of the Covid-19 business shock, the Federal Reserve used an emergency rate cut between meetings.

But it was nowhere near sufficient to get the credit machinery running as it would need to and to get the market to bottom. The extent of the income losses and credit problems were severe and interest rate cuts wouldn’t be adequate.

Nonetheless, the Fed was relatively fast by traditional standards. The market bottomed on March 24 after topping on February 19.

US stocks still fell about 35 percent over that short period, though small caps were down about 47 percent. If small businesses had an index to themselves to gauge their market value, it would have been even worse.

The nature of the crisis was unique due to business shutdowns drying up revenue completely in many industries throughout the developed world (e.g., restaurants, movie theaters, brick-and-mortar retail).

Sometimes it can take years for policymakers to act decisively.

The quickness and aggressiveness of the response are among the most influential factors in determining how long and how severe the depression phase and market downturn will be.

Sounds currency policies

Policymakers must also run a sound currency policy. This means the currency shouldn’t produce large declines or rises in relation to major trading partners, other leading currencies, or relative to goods and services prices.

Running a sound currency policy helps produce a sound credit system that works for both borrowers and lenders.

China, for example, has been managing its exchange rates and the interest rates that have a big influence on the capital inflows and outflows that move exchange rates since 1985.

Who gets saved and who doesn’t

There is also the economic and social factor of determining how the costs of the downturn will be divided among various parts of society.

These include the government, depositors, bondholders of varying levels of seniority, equity holders, and so forth. Naturally, this becomes a hot political topic.

Generally, the institutions that are not systemically important are forced to take their losses internally. This means the equity holders, or owners of the business. If they fail, then they are allowed to go bankrupt.

Sometimes these types of companies, if they do fail, or see their market values severely decline, are merged with healthy institutions. They are typically bought at steep discounts relative to their all-time highs.

Buyouts and/or mergers and acquisitions is the case for insolvent companies more than three-quarters of the time.

In other cases, their assets are liquidated. The equity holders are often zeroed and bondholders, depending on their seniority, are forced to take a haircut.

In some cases, their assets are transferred into a special purpose vehicle that’s set up by the government to sell off their assets to various buyers. This can include buildings, machinery, factories, and other equipment.

Policymakers need to recognize that the solvency of the banking system is critical and keeping it viable is necessary. So, typically ensuring adequate liquidity and solvency is important for the major financial institutions.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, guarantees (or larger guarantees) of bank liabilities have been provided in developed market countries.

Sometimes, though not commonly, government-sponsored bank recapitalizations are done across the commercial banking system. But more commonly, such recapitalizations target only systemically important institutions.

Some politicians ask that all financial institutions not get to a level such that they can be classified into such a category to avoid moral hazard concerns.

Credit protections

Creditor protections are defined and have clear priorities.

Small depositors receive government protections up to a certain amount, generally defined as deposit insurance (e.g., $250k in the US under FDIC and NCUA insurance). In nearly each case, the losses are zero or small.

Coverage is typically expanded during the crisis to ensure that banks don’t face runs and such that they have adequate liquidity.

Even when deposit insurance is absent, depositors often have seniority.

Generally, when depositors do take losses, they are on foreign-exchange deposits where the money lost value when converted back to their domestic currency (i.e., relative to its value when deposited, akin to an investment loss).

When institutions are insolvent and left to fail, it’s generally the large depositors, junior debt holders, and equity holders who are forced to take large losses. This is generally the case regardless of whether the institution is deemed systemically important or not.

Equity recapitalizations and protection of senior and subordinated debt holders are mostly seen in the developed world and rarely in the developing world (i.e., emerging markets).

Sometimes policymakers will favor domestic creditors over foreign creditors. This is particularly true when deposit insurance programs beginning to deplete their funds and/or these entities are part of the private sector.

At the same time, governments normally try to prioritize loans from multinational organizations such as the IMF, World Bank, and BIS.

These are lenders of last resort for countries undergoing financial stress and paying them back helps to keep open these funding channels in the future, should they be needed.

Policymakers normally react to the large amounts of failed borrowers by implementing regulatory reforms.

In some cases, these changes are moderate and sometimes they are substantial. Sometimes they make a positive impact and sometimes they make matters worse.

Changing how banks operate is a common change. This was the case in the 1930s with deposit guarantees.

After 2008, another bank-related crisis, the Volcker rule and Dodd-Frank were put into place. This legislation placed restrictions on bank activities and gave greater oversight power to the Federal Reserve to regulate systemically important institutions.

These changes also include matters like requiring the banks to improve their credit standards, larger equity capitalization requirements, new competition within the banking system (e.g., allowing foreign entrants), and removing protections to lenders to remove moral hazard concerns.

The political process plays a large role

Politics makes a difference in what types of reforms are made.

Sometimes these reforms distort the market-based incentives associated with the private sector. This can limit the amount of lending that can flow to creditworthy borrowers and increase the likelihood of credit problems emerging going forward.

In some cases, regulations help improve the flow of credit to creditworthy borrowers, protect households, and can effectively reduce the likelihood of credit problems in the future.

How bad assets are managed

Getting markets to bottom is heavily determined on how well bad assets are managed and restructured.

When failed lenders (or existing lenders) have bad/non-performing assets that they need managed, there are two basic ways this traditionally plays out:

i) They remain on the balance sheet of the original lending institution to manage

ii) They are transferred onto a different balance sheet (i.e., a separate entity) to be disposed of or restructured

The first option is a little bit more common than the second.

There are various ways that these non-performing loans can be managed:

i) extending the maturities of the loans or writing down a portion of their values (or all of their values)

ii) sales of the loans and/or assets to other institutions or investors

iii) swapping debt for equity, or what are effectively asset seizures – i.e., all or a portion of the bondholders become claimants on these assets, since the equity holders are typically wiped out

iv) securitizations of these assets to make them saleable to a variety of different parties

The use of a separate asset management company for these bad debts is generally better for accelerating the rate at which the debt problem can be effectively managed.

It allows banks (at least those that are continuing to operate) to help consolidate the debts on a separate single balance sheet and coordinate the process of managing their sales and restructurings.

Meanwhile, the banks themselves (the normal entities) can resume lending operations.

Separate asset management companies are normally publicly owned entities and they are required to manage and sell the assets they are transferred within a stipulated timeframe.

At the same time, their goal is to minimize the impact on the budget of the central government while also reducing any disruption to financial markets.

Some asset management companies will have explicit goals of restructuring bad debts to reduce their burden over time.

They are not able to work effectively in recognizing and restructuring non-performing assets when there are constraints placed against them. This can mean political, legal, or funding matters that inhibit their ability to operate well.

As a result they are generally financed by some type of direct debt issuance.

The need for a separate asset management company declines when:

i) the original bank or lender is a state-sponsored entity

ii) if the debts are manageable, such that they are not too large to be managed effectively

iii) alternative existing resolution mechanisms already exist

iv) the technical knowledge and expertise required to set up separate a asset management company is not available

Systemic vs. Non-Systemic Institutions

There is a clear distinction between how institutions are handled that are systemically important – or strategic in other ways (e.g., intellectual property, already a government or quasi-government structure, employ a lot of workers (especially high-skilled ones)) – and those that are not.

Systemically important

Policymakers will ensure that systemically important lenders and borrowers, or strategically important ones, take steps to ensure that the businesses remain as “going concerns” (financially viable).

Generally this occurs by restructuring the debt to ensure that the debt service commitments are manageable.

This is accomplished by reducing the amount of existing debt, lowering their interest rates to reduce the incremental payment requirements, or expanding out the maturities of the debt.

Debt for equity swaps are also common, essentially forcing the equity holders to absorb the losses.

Policymakers may also introduce new types of lending programs to ensure liquidity is sufficient.

Non-Systemic

The non-systemically important borrowers are normally left to restructure their debt commitments with private lenders. If they cannot do that, they are allowed to go broke and liquidated.

Central governments often will work to reduce the debt burdens facing the household sector.

Asset management companies may also choose to restructure their debts rather than foreclosing on them to help with their mandate of ensuring they get the maximum value for them.

Austerity

During the depression phase of a downturn, policymakers typically try austerity because that’s the easiest and most straightforward thing to do.

It’s natural to want the borrowers and lenders who got themselves into trouble to bear the costs for their actions.

But the issue is that austerity, even on a severe level, isn’t enough to bring debt levels down back in line with income.

This is because when spending is cut, incomes are also cut because one person’s spending is another’s income.

So, the spending cuts generally need to be extreme in order to get adequate reduction in the debt-to-income ratios such that the economy can find a new equilibrium and begin growing again.

Moreover, when the economy contracts, governments’ tax takes and overall revenues generally fall.

For governments with large progressive tax schemes (i.e., those making higher incomes have a larger share of their income going toward taxes), the drop in revenues can be especially severe. The incomes of the highest earners tend to be the most volatile.

Yet when the economy falls, the demands on the government increase. This often causes fiscal deficits to balloon outward.

Emerging markets often face balance of payments crises when they run into issues with deficits.

This is when people anticipate that a lot of debt needs to be issued to fund them and people want to get their money out of the country due to the likelihood of currency depreciation and investment losses.

Developed markets have less of an issue because of their reserve currency status, which means there’s at least decent demand for their credit. This reduces the likelihood of large depreciations and credit problems.

Seeking to remain fiscally responsible, governments typically try to raise taxes. Politically countries are also more likely to shift left, electing politicians who are more amenable to the idea of raising taxes.

But, if not done well, higher tax policies often chase away the top earners who have just suffered hits to their assets and incomes and are facing another hit through higher taxes or new taxes.

Naturally, they try to move their assets and/or themselves to tax-friendly jurisdictions.

Money Creation (also known as “Printing Money”)

Money creation is used to get asset markets to bottom and to stimulate the economy.

“Runs” commonly develop on lending institutions so people can be sure they’ll get their money. This is especially true for those that aren’t backed by the government.

The monetary and fiscal arms of the central government will need to decide which lenders and which depositors are worth saving (i.e., the systemically important ones) and which ones should be allowed to sustain losses.

This also needs to be done in a way that maximizes the safety of the financial system and economy and minimizes the costs and burdens to the government and its finances.

During big market downswings when stress against financial institutions is particularly high, various types of guarantees are provided to important banks. Some of them may be nationalized.

Due to laws, regulations, and the various political matters surrounding this process, how fast and how well this plays out can vary.

Some of the money needed to keep the banks liquid comes from the central banks (monetary side) by creating it. This is usually quicker because it is less political. Some money comes from the fiscal side by being approved through the budget process.

Governments will do both, with varying extents on what amount comes from central banks and what amount comes from fiscal policymakers.

Money is provided to both essential banks, with some going to non-bank entities as well that are deemed important enough to save.

After backstopping the important entities, they must ease the credit problems and stimulate the broader economy.

The government at this point will have issues collecting more revenue through taxation. It will also be hard for them to borrow the money.

So, they are forced to choose between:

i) “printing” the money and buying the government’s debts, or

ii) having local and central governments and the private sector compete for a limited amount of money

The former is stimulative, the latter is deflationary and tightens money further. They always choose to print more money.

Usually, the money creation comes in smaller quantities that are not enough to remedy the imbalance between the demand for money and the supply of it to reverse the market downturn.

They are generally enough to produce some spurts of rallies in financial assets and in the real economy.

In the Great Depression, the bear market saw a peak to trough decline of 89 percent in financial assets. But there were six rallies of between 16 to 48 percent during this period.

All of these rallies came as a result of the government wanting to reduce the imbalance between a lot of assets for sale and not enough liquidity available to find buyers.

The combination of guarantees, printing money, and buying assets in sufficient quantity moves the markets from the depression phase back into expansion. The markets bottom before the economy. This was the same process in the US in 1932, 2008-09, and 2020.

Stimulative monetary policy is important in getting markets and economies to bottom when lowering interest rates no longer works effectively. But it is generally not adequate on its own.

Systemically important institutions must be kept running, particularly when they’re at risk of failing.

Policymakers need to act immediately to:

i) Ensure adequate liquidity. Because credit is contracting and liquidity is tight, the central bank can help ensure that liquidity is put into the financial system.

First, they start with lower duration government securities (bonds), which are the safest. This is the standard process of how central banks lower short-term interest rates.

When that’s out of room, they move on to longer duration government and government-backed securities.

If necessary, they can move on to corporate credit and other riskier forms of collateral, law permitting. They may also help backstop a wider range of financial institutions that are typically outside the purview of their lending operations.

ii) Not only liquidity support, but help backstop systemically important institutions.

The typical first step is to incentivize the private sector to help rectify the problem. This can include supporting mergers between healthy banks and insolvent/troubled banks.

Regulatory measures can be taken to help get more capital to the private sector. To ensure solvency on the basis of capital ratios, changes in accounting rules can be made to avoid technical insolvency.

This gives institutions more time to improve their situations financially and earn their way out of their current financial problems.

Mark-to-market accounting was part of the reason why the 2008 financial crisis was worse than the one suffered in the 1980s. More loans were traded on the exchanges in the 2000s than the 1980s, so keeping tabs on technical solvency and insolvency was easier.

iii) Place guarantees on debt issuance, deposits, and various bank liabilities.

For institutions whose demise would threaten the ongoing operation of the financial system or economy, backstopping them with capital infusions limits or does away with this risk.

Sometimes, governments can force liquidity to remain in the banking system. For example, they can mandate a stop to all share buyback, as the US Federal Reserve did in 2020. They can also mandate no increases in dividends or special distributions.

In other cases, the central bank can impose freezes on deposits. This is generally not prudent because it increases panic.

Because are most incentivized to get their money out of something when measures might be taken to ensure they can’t.

This is true for deposits at banks and also when countries impose capital controls to prevent money from leaving a country to control their balance of payments.

However, sometimes deposit freezes can be necessary when there is no other way to keep liquidity in the banking system.

iv) Governments can also nationalize the banks, recapitalize them, or cover their losses. When everything else fails, governments will step in to recapitalize insolvent banks.

Stabilizing lenders and maintaining the flow of credit in an economy is critical to preventing a credit crunch from spreading and getting worse.

Certain institutions are critical to an economy ensuring this process that would make them painful to lose even if they’re not profitable in a temporary sense.

Systemic importance goes beyond banks and financial institutions

In some countries, this would be similar to protecting their oil industry.

Even if oil prices going into a downswing and profitable exploration and production activities are non-existent, oil is a strategically important commodity.

Given their criticalness, governments still want those companies operating. So, many countries have gone on to nationalize their oil companies for those that have ample amounts of natural energy resources.

The same goes for airlines and other forms of important commerce, such as passenger train systems (e.g., Amtrak in the US).

Oil, airlines, and other industrial companies also face competitive issues related to high capital intensity, thin margins, and the large amount of consolidation necessary to achieve scale. At times, this makes private sector participation in these sectors difficult.

So some governments come in and take over the industry to have greater control over important industries and infrastructure.

Countries with a large concentration of systemically important institutions in the hands of the private sector can also choose to provide loans and capital infusions into these companies in lieu of nationalization.

Wealth redistribution

Wealth gaps tend to increase during market bubbles. This becomes a socially and politically divisive topic as those with lower net worths see the net worths of asset holders increase.

They perceive the system as increasingly unfair and “favoring the rich”.

How much inequality is tolerated before there’s major conflict is dependent on the society. Some societies will tolerate more inequality than others.

But in general, if there’s an economic downturn there will inevitably be some level of social, political, and economic conflict between those who own the bulk of the wealth (a small percent) and those who don’t.

More broadly, there is typically conflict between the political left and right. How people and the political system act are also important factors in how the economy and society pull through the downturn.

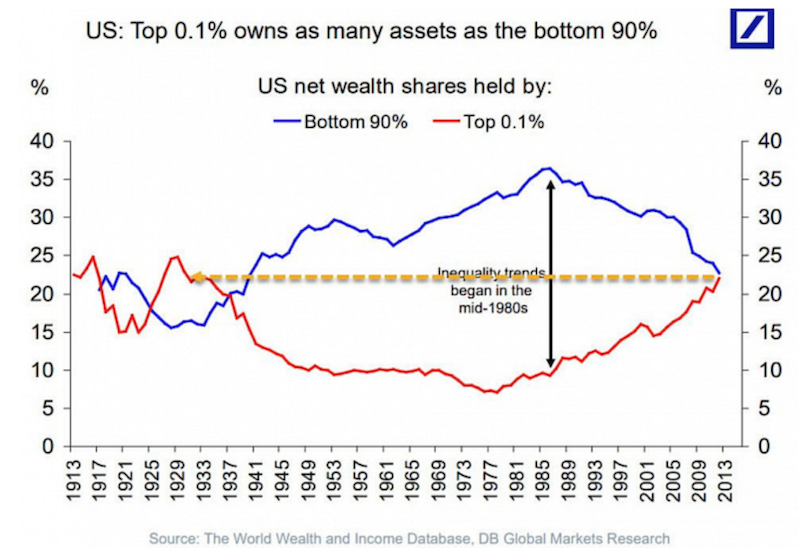

Like in the 1930s, the wealth inequality after the financial crisis and after the Covid-19 pandemic are high, with the top 0.1 percent owning assets that are approximately equal to those of the bottom 90 percent combined.

Raising taxes on the wealthy becomes more politically popular because they tend to make a lot of money during the boom period.

Those in the financial sector are especially condemned because many perceive them to have caused many of the problems associated with financial crises because of their excessive speculative actions.

Moreover, the central bank’s purchase of financial assets disproportionately benefits those who own financial assets and assets of most kinds.

Generally, such downturns create political shifts to the left, whose leaders call for more redistribution and higher taxes on those who have high wealth and incomes.

The rich generally want to move their assets to be protective. This itself has an impact on financial asset and currency markets (i.e., weakens them further).

It can also contribute to a hollowing out of these areas. The ones who earn the large incomes are also the big income taxpayers. If they leave, that reduces overall revenues, and these areas suffer declines in property values and services.

Higher taxes generally take the form of higher taxes on income, consumption, and property. These are the most effective at generating revenues.

Taxes on inheritance and wealth are sometimes increased as well. The extent to which wealth taxes can be applied varies heavily depending on where you go.

The topic of wealth taxes

Wealth taxes have been deemed unconstitutional in the US and a major court decision would be required for them to be implemented in the traditional ways of taxing wealth. But they have been applied to varying extents in other countries and throughout time.

Calls for wealth taxes tend to coincide with periods of higher social tensions, when there is economic weakness, higher levels of inequality, social upheaval between the “capitalists” and “socialists”, and higher than normal political polarity.

Inheritance and wealth taxes are nonetheless rarely effective. Because most wealth is illiquid it’s hard to collect revenue on it.

This forces taxpayers to sell assets to make their tax payments. This undermines the process of building capital for business purposes (known as “capital formation”), reduces financial asset prices, and overall creditworthiness (which in turn feeds into spending and income in a negative way).

This shrinks the total amount of wealth in a society and creates greater conflict on how to divide up available resources.

In turn, this creates even more conflict, which leads to political battles between opposing leaders who want to take control of the situation to bring about order.

During these periods, democracy is challenged more by autocracy. Some believe the drawbacks of autocracy outweigh democracy when situations run out of control, decision-making is slow, and order needs to be restored.

In the 1920s and 1930s, after a widespread economic depression hit the developed world, Germany, Japan, Italy, Spain, and many other smaller nations turned away from democratic decision-making and more toward strong autocratic leaders who promised to regain control.

The three major democracies (the US, UK, and France) all became more autocratic as well in response to violent social behavior and a reduced respect for law.

During periods of greater upheaval, more individuals believe that more centralized and autocratic decision making (i.e., less political compromise) can be better suited to the environment than less centralized and more democratic decision making.

The belief is not without merit depending on the general quality of the decision making. China is a more autocratic system, which brings with it the benefit to being able to take control and get things done more quickly politically. Like any system there are pros and cons.

Tax and redistribute rarely contribute to ending debt crises

Regardless of the tax and redistribute policies implemented, they rarely move the needle when it comes to rectifying the debt and income imbalances that exist in an economy.

Governments are already trying to optimize their tax take during good times. When incomes go down during the bad times, it becomes harder to raise taxes in any meaningful quantity.

Cutting government spending is also extremely politically unpalatable as a means of keeping deficits in check. People rely on that government spending for income or essential services.

Politicians don’t want to be voted out. Accordingly, they will spend what they need to out of self-interest, leaving the financial situation of their jurisdiction to those who come after them.

So, naturally deficits will balloon depending on the extent of the economic and financial problems and the government will turn to more stimulative monetary policy and liability guarantees.

The exception is when there are revolutions and large social upheavals where large amounts of wealth are effectively seized and a large amount of property is nationalized. When the causes people are behind are more important than the systems available for resolving their disagreements, the systems are often in jeopardy.

‘Debt eats equity’

There is an old saying that ‘debt eats equity’.

This means that debts have to be paid above all else.

Debt is cheaper than equity because it is senior in the capital structure. But it has to be paid first.

For example, if you own a house (which means you have a form of equity ownership) and you can’t pay the mortgage payments, the house will be sold or taken away by the creditor (the bank or whoever made the loan). The house is collateral for the loan.

This means the creditor will get paid ahead of the owner of the house.

The general idea is that when:

- your revenue (or income in the case of an individual or family) is less than your expenses and

- your assets are less than your liabilities (i.e., debts)…

…it means that assets will need to be sold if there’s not a reversal of these circumstances.

Money (what payments are settled with) and credit (a promise to pay) can easily be created by central banks.

Individuals, corporations, nonprofits, and local and central governments like it when central banks create a lot of money and credit because all this creates spending power.

When this cash and credit are spent, it makes most goods, services, and investment assets go up in price.

But it also creates debt that has to be repaid, which requires people, companies, nonprofits, and governments to eventually spend less than they earn, which is not easy to do. This is accordingly why money, credit, debt, and economic activity, in general, are inherently cyclical.

Conclusion

In this section, we covered the four basic ways that policymakers get an end to the bleeding so the markets and economy can recover again.

Knowing what to expect can help your trading. Studying history can help inform the future. If you choose to trade the markets by betting on what’s going to be good and not good, you will be required to anticipate what’s going to happen ahead of time.

Though you can also remain immune to them if you choose to by having a more balanced asset allocation or adopting more market neutral strategies.

In the next article of this series, we will cover the market recovery phase.